After we fix the communication model, synchrony, asynchrony, or partial synchrony, and a threshold adversary we still have 5 important modeling decisions about the adversary power:

- The type of corruption (typically: passive, crash, omission, or Byzantine).

- The computational power of the adversary (typically: unbounded, computational, or fine grained).

- The adaptivity of the adversary (typically: static, adaptive, or strongly adaptive).

- The visibility of the adversary (typically: full information or private channel).

- The mobility of the adversary (typically: traditional or mobile).

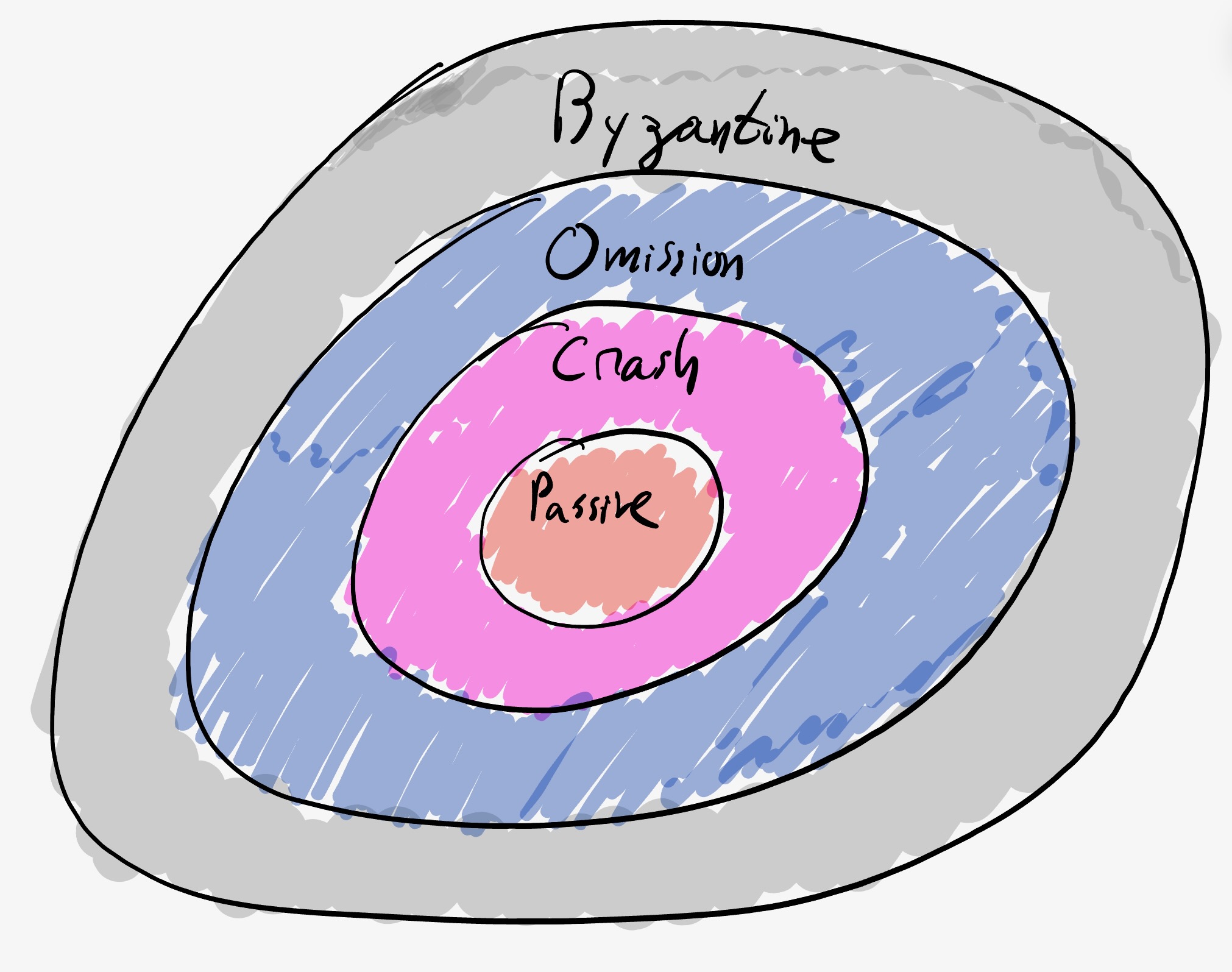

1. Type of corruption

The first fundamental aspect is what type of behavior the adversary can inflict on the $f$ parties is can corrupt. There are four classic types of corruption: Passive, Crash, Omission, and Byzantine.

Passive: a passively corrupted party must follow the protocol just like an honest party, but it allows the adversary to learn information. A passive adversary (sometimes called Honest-But-Curious or Semi-Honest) does not deviate from the protocol but can learn all possible information from its view: i.e., the messages sent and received by parties it controls. A failure in this case is if the passive adversary learns information that the protocol designer wanted the adversary not to learn.

Crash: in addition to passive, once the party is corrupted, the adversary can decide when to cause it to stop sending and receiving all messages.

Omission: in addition to passive, once corrupted, the adversary can decide, for each message sent or each message received, to either drop or allow it to continue. Note that the party is not informed that it is corrupted. Sometimes there is a separation to send omission corruption and receive omission corruption.

Byzantine: this gives the adversary full power to control the party and take any (arbitrary) action on the corrupted party. Sometimes this model is called active corruption or arbitrary corruption.

Note that each corruption type subsumes the previous one.

There are other types of corruption. Most notable are variants of Covert adversaries. Covert adversaries can be used to model rational behavior where there is fear (utility loss) from punishment through some form of detection.

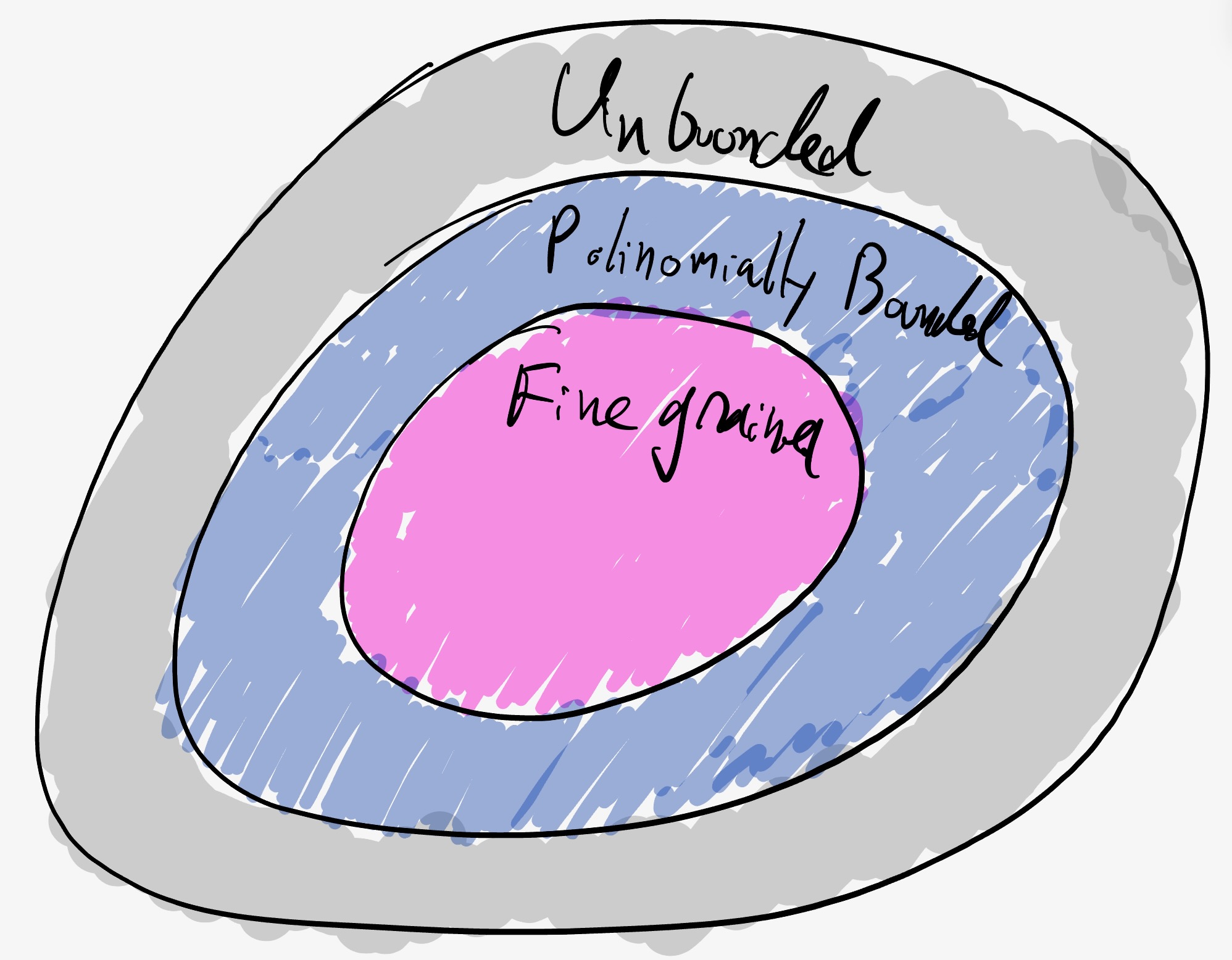

2. Computational power

The computational power of the adversary is the next choice. There are two traditional variants and one newer one:

- Unbounded: the adversary has unbounded computational power. This model often leads to notions of perfect security or statistical security.

- Computationally bounded: the adversary has a polynomial advantage in computational power over the honest parties. Typically, this means that the adversary cannot (except with negligible probability) break the cryptographic primitives being used. For example, typically assume the adversary cannot forge signatures of parties not in its control (see Goldreich’s chapter one for traditional CS formal definitions of polynomially bounded adversaries).

- Fine-grained computationally bounded: there is some concrete measure of computational power and the adversary is limited concretely. This model is used in proof-of-work based protocols. For example, see Andrychowicz and Dziembowski for a way to model the hash rate. It is also needed for Verifiable Delay Functions.

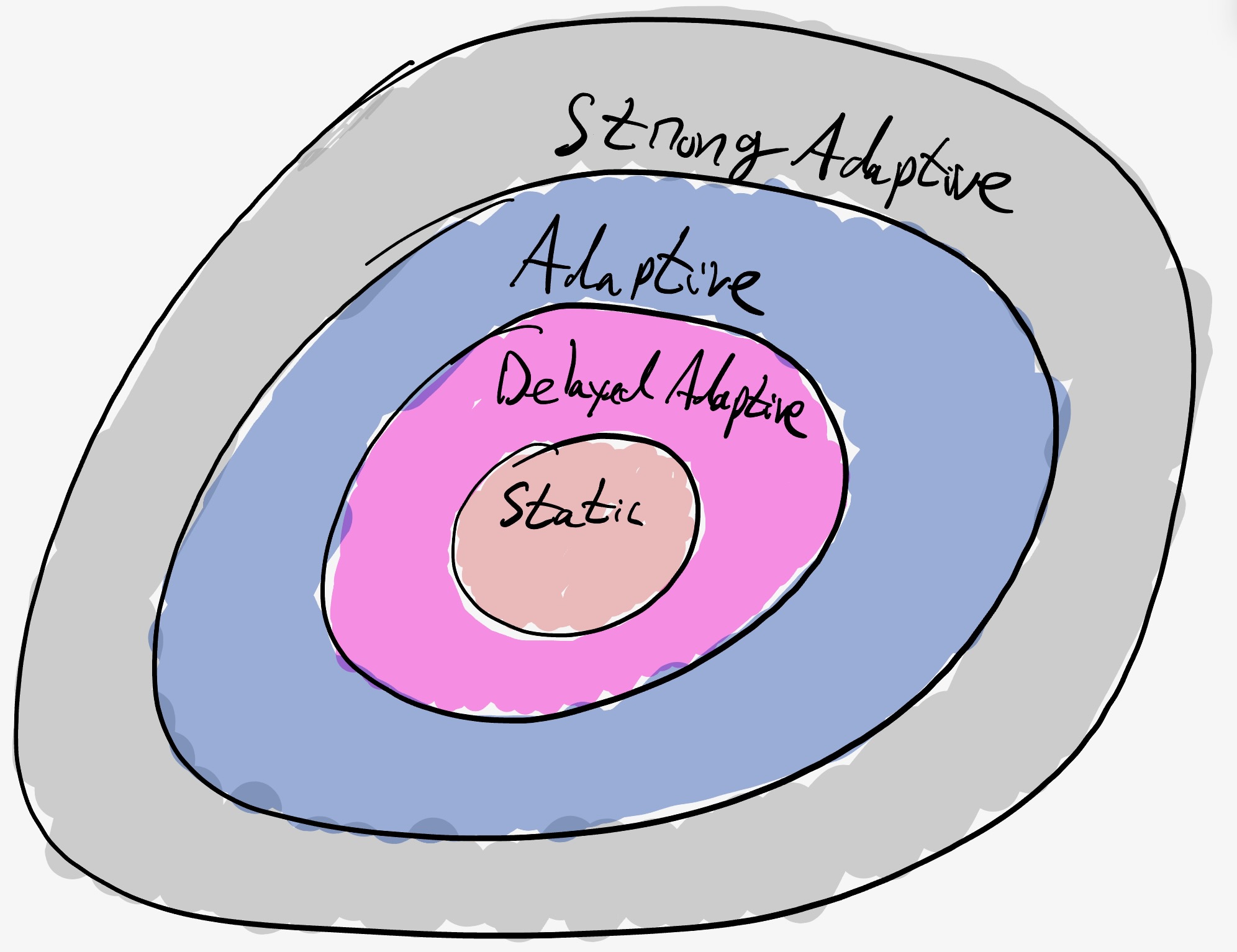

3. Adaptivity

Adaptivity is the ability of the adversary to corrupt dynamically based on information the adversary learns during the execution. There are two basic variants: static and adaptive. The adaptive model has several sub-variants.

-

Static: the adversary has to decide which $f$ parties to corrupt in advance before the execution of the protocol. Note that this is always sufficient when the protocol is deterministic.

-

Adaptive: the adversary can decide dynamically as the protocol progresses who to corrupt based on what the adversary learns over time. There are three main sub-variants:

- Strong Adaptive: once the adversary asks to corrupt, the party is immediately corrupted. Moreover, messages sent from the party before corruption that have not yet arrived can be erased by the adversary. Some lower bounds only work in this model.

- Adaptive: once the adversary asks to corrupt, the party is immediately corrupted. Messages sent from the party before corruption cannot be erased (so will eventually arrive in asynchrony or in arrive in at most $\Delta$ time in synchrony).

- Delayed Adaptive: once the adversary asks to corrupt, the party is corrupted at the end of the round ($\Delta$ time in synchrony, or once the party decides to listen to a port in asynchrony). Often in this model is also critical that honest parties can erase some information in order to get forward security.

4. Visibility

The visibility is the power of the adversary to see the messages and the states of the non-corrupted parties. Again, there are two basic variants:

- Full information: here we assume the adversary sees the internal state of all parties and the content of all message sent. This often severely limits the protocol designer. See for example: Feige’s selection protocols, or Ben-Or et al’s Byzantine agreement.

- Private channels: in this model, we assume the adversary cannot see the internal state of honest parties and cannot see the internal content of messages between honest parties. Each time a message between two honest parties is sent, the adversary learns the source, target, and message size. Depending on the communication model, it can decide to delay it by any value that is allowed by the communication model.

For models that are round-based, another visibility distinction is the adversary’s ability to rush. When does the adversary see the messages sent to parties it controls? In the rushing adversary model, the adversary is allowed to see all the messages sent to parties it controls in round $i$ before it needs to decide what messages to send in its round $i$ messages. In the non-rushing adversary model, the adversary must commit to the round $i$ messages it sends before it receives any round $i$ messages from non-faulty parties.

5. Mobility

In the traditional model the adversary is allowed to corrupt honest parties will a budget of $f$, but is not allowed to un-corrupt (or heal) corrupt parties back to being honest. In the mobile model the adversary is allowed to dynamically decide to corrupt and un-corrupt parties. The total number of corrupted parties at any given time is at most $f$, but over time the set of corrupted parties may change. It is often required that there is a gap between the time the adversary un-corrupts one party and the time it is allowed to corrupt another. This model was introduced by Ostrovsky and Yung and exemplified by proactive secret sharing. Another modeling decision is whether the party is aware that it is un-corrupted.

More models

Over the years there have been many variations - here is an incomplete list (lets us know in comments about more).

Mixed corruptions

In some cases we are interested in a mix of say $f$ Byzantine and $k$ crash corruptions (for example here) or any other mix.

Sleepy model

In the sleepy model of Pass and Shi, in addition to being either honest or corrupt, parties can be either active or inactive each round. The assumption is that the threshold bound on the adversary holds at each round on the actual number of active parties in that round. This is sometimes called the dynamic participation model.

Mobile sluggish

One of the challenges in the mobile model is the fact that the adversary can accumulate the private keys of parties. In the weak synchrony model (also called mobile sluggish), the adversary is allowed to corrupt either via a Byzanitne corruption (that is not mobile) or a mobile sluggish corruption. Critically, the sluggish corruption allows the adversary to delay messages to and from the corrupted party but not to learn its private keys. Hence, allowing sluggish corruptions to be mobile does not allow the adversary to accumulate private keys.

Flexible model

The Flexible BFT model introduces two variations. First, a model where different properties are held under different threshold assumptions. Second, a model where the same protocol may serve different clients, where each client may have a different adversary threshold in mind.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Alin Tomescu, Kartik Nayak and Gilad Stern for insightful comments.

Please leave comments on Twitter