Lower bounds in distributed computing are very helpful. They prevent us from wasting time on impossible tasks :-). More importantly, they help us focus on what is optimally possible or how to circumvent them by altering assumptions or problem formulation.

It’s either easy or impossible – Salvador Dali

In this post we discuss a classic impossibility result:

DLS88 - Theorem 4.4: It is impossible to solve Agreement under partial synchrony against a Byzantine adversary if $f \geq n/3$.

As described in an earlier post on partial synchrony, either we have a GST event at an unknown time (or we have an unknown $\Delta$). Thus, the time to decide cannot depend on GST occurring (or on knowing $\Delta$).

Seeking a contradiction, let us assume there is a protocol that claims to solve Byzantine Agreement with $f \geq n/3$ Byzantine parties. Divide the $n$ processors into three sets: $A$, $B$, and $C$ each with at least one party and at most $f$ parties in each set. We consider the following three worlds and explain the worlds from the view of $A$, $B$, and $C$. In all three worlds, we will assume that all messages between $A \longleftrightarrow B$ and $B \longleftrightarrow C$ arrive immediately; but all messages between $A$ and $C$ are delayed by the adversary.

For the proof, we introduce two simple but powerful techniques. These two techniques are used in many other proofs so it is worthwhile to get to know them.

The first is indistinguishability, this is where some parties cannot distinguish between two (or more) possible worlds. Their views look the same, so they must reach the same decision in both worlds. This leads to the following initial proof approach: imagine that there were two worlds: World 1 and World 2. Imagine that in World 1 the honest must decide 1 and in World 2 the honest must decide 0. If there was some honest party for which World 1 and World 2 are indistinguishable then we would drive a contradiction. Unfortunately we cannot use such a simple argument for this lower bound.

The second technique is hybridization, this is where we build intermediate worlds between the two contradicting worlds and use a chain of indistinguishability arguments leading to a final contradiction.

Here we go, let’s define Worlds 1, 2, and 3:

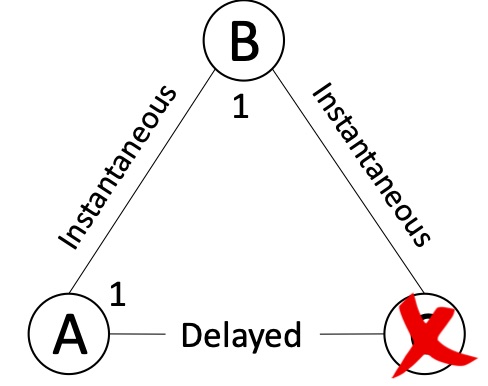

World 1:

In World 1 parties in $A$ and $B$ start with the value 1. Parties in $C$ have crashed. Since $C$ is at most $f$ participants, the parties in $A$ and $B$ must eventually decide. For agreement to hold, all the parties in $A$ and $B$ will output 1. From $A$’s (and $B$’s) perspective, they cannot tell if $C$ crashed or if its messages were delayed.

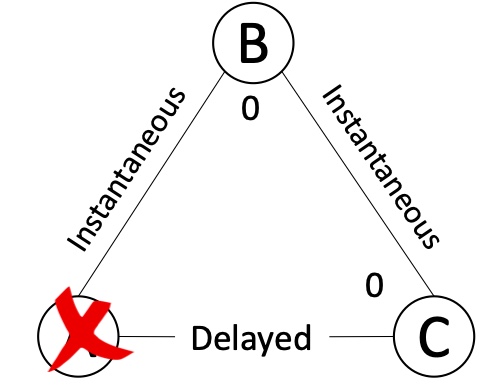

World 2:

World 2 is similar to World 1, with the roles of $A$ and $C$ interchanged. The parties in $B$ and $C$ start with the value 0. Parties in $A$ have crashed. $C$ cannot tell if $A$ crashed or if its messages were delayed. So all the parties in $C$ and $B$ will output 0.

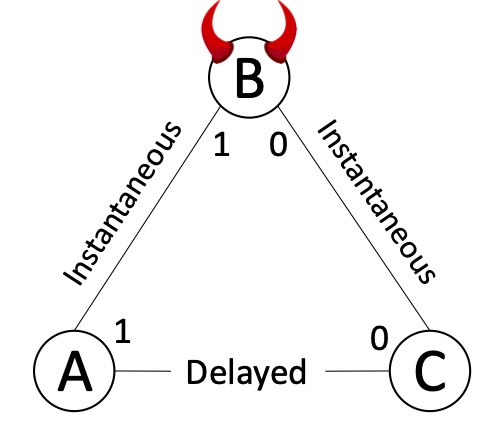

World 3:

World 3 will be a hybrid world: $A$’s view will be indistinguishable from its view in World 1, and $C$’s view will be indistinguishable from its view in World 2. $A$ will start with value 1 and $C$ will start with value 0. The adversary will use its Byzantine power to corrupt $B$ to perform a split-brain attack and make $A$ and $C$ each believe they are in their own world. $B$ will equivocate and act as if its starting value were 1 when communicating with $A$ and as if it were 0 when communicating with $C$. If the adversary delays $A$–$C$ messages long enough for them to decide, then by indistinguishability $A$ commits to 1 and $C$ to 0 (since decision time cannot depend on GST or $\Delta$). This violates the agreement property.

Some important observations:

-

The impossibility holds even if the adversary is static, i.e., we fix the set $B$ that the adversary corrupts before starting the execution.

- The impossibility holds even if there is a trusted setup phase, for example if the parties have a PKI setup.

-

The impossibility holds even if the adversary can only cause omission failures and restarts, see the post on the rollback adversary.

-

The impossibility above importantly assumes (i) a Byzantine adversary for $B$, and (ii) messages between $A$ and $C$ can be delayed sufficiently. Even if one of these two conditions does not hold, we can tolerate $f \geq n/3$. If we only have crash faults, then Paxos and many other protocols can tolerate a minority corruption. If messages are guaranteed to arrive within a fixed known time bound (i.e., assuming synchrony), then we can tolerate a minority corruption (see for example here, here, and here).

-

For agreement to hold, it is essential that if one party decides on a value, all others decide on the same value. Under partial synchrony, since parties may not communicate before deciding, they must ensure a majority of honest parties agree on a value first (otherwise two minorities can commit to different values). Among $3f+1$ parties, $f$ can be Byzantine; thus $f+1$ honest parties form a majority among the remaining $2f+1$. Hence, partially synchronous protocols typically communicate with $2f+1$ (out of $3f+1$) parties before deciding: $f+1$ honest majority + (up to) $f$ Byzantine. On the other hand, under synchrony, in synchrony parties typically communicate with $f+1$ out of $2f+1$ parties.

-

A similar lower bound holds for crash (or omission) failures if $n \leq 2f$ in the partial synchrony model. See this post on this and the CAP theorem for more.

- This lower bound holds for Broadcast (aka Reliable Broadcast) in partial synchrony, not just for Agreement. A lower bound for broadcast implies a lower bound for verifiable secret sharing and for multi-party computation.

Please leave comments on Twitter