Bitcoin’s underlying consensus protocol, now known as Nakamoto consensus, is an extremely simple and elegant solution to the Byzantine consensus problem. One may expect this simple protocol to come with a simple security proof. But that turns out not to be the case. The Bitcoin white paper did not provide a proof. Several academic papers (e.g. Garay, Kiayias, Leonardos, and Pass, Seeman, shelat and Kiffer, Rajaraman, shelat) later presented rigorous proofs. These proofs are fairly complicated even for experts and quite hard for practitioners, beginners, and students to follow.

This post gives a walkthrough of a simple proof I wrote recently. Anyone with knowledge in basic probability should be able to follow the proof. You are encouraged to watch the talk or read the full proof.

Model and assumptions

I assume you are familiar with how Nakamoto consensus works. Below is a concise description that contains all the important details this post needs. (If you need a more detailed explanations and descriptions, there are plenty of good resources online.)

- Longest chain wins. A node adopts the longest proof-of-work (PoW) chain to its knowledge (breaking ties arbitrarily) and attempts to mine a new block that extends this longest chain;

- Disseminate blocks. Upon adopting a new longest chain, either through mining or by receiving from others, a node broadcasts the newly acquired block(s);

- $k$-confirmation commit. A node commits a block if it is buried at least $k$ blocks deep in the longest chain adopted by that node. Here, $k$ is a security parameter (6 is common in practice) that controls the probability of incorrect commit.

We make two assumptions. Firstly, PoW mining is modeled by Poisson processes. We use $\alpha$ and $\beta$ to denote the mining rates of honest nodes and malicious nodes, respectively. Secondly, the network is synchronous, i.e., there is a network delay upper bound $\Delta$ between any pair of honest nodes.

Before moving on to the actual proof, we give some background on Poisson processes and make a few remarks on the assumptions. A Poisson process models arrivals of a stream of memoryless events. It is parameterized by a rate parameter $\lambda$. During a time window of duration $t$, the probability of having $k$ events is $e^{-\lambda t} \frac{(\lambda t)^k}{k!}$. In our context, each event refers to the creation of a new block and this process is memoryless in the sense that the time till the next block does not depend on how much time has already elapsed since the previous block. Regarding the network model, we note that we assume synchrony but not lock-step execution. Some papers mistakenly refer to the non-lock-step synchrony assumption as “asynchrony” or “partial synchrony”. Our previous post explained the differences. It is not hard to show that Nakamoto consensus is insecure under asynchrony or partial synchrony. We will elaborate on this issue in a future post.

Our goal in this post is to prove that Nakamoto consensus solves state machine replication, i.e., it guarantees safety and liveness:

- safety: Honest nodes do not commit different blocks at the same height.

- liveness: Every transaction is eventually committed by all honest nodes.

Intuition of the proof

Here is a high-level plan to prove safety. (The liveness proof is easier and will come as a by-product along the way.) We call a block mined by an honest miner an honest block and a block mined by a malicious miner a malicious block. Ideally, we want to prove that honest blocks contribute to the safety of Nakamoto consensus while malicious blocks undermine it. If this were true, we would be able to prove Nakamoto consensus safe as long as $\alpha > \beta$ (i.e., the well-known honest majority assumption).

Unfortunately, the above simple argument does not hold due to network delays. In order for all honest blocks to contribute to safety, they must extend one another and form a chain. But in reality, we know the chain can fork even if the malicious nodes do not do anything bad. In this case, not all honest blocks make it to the longest chain, and hence, not all of them contribute to safety. The crux of the proof is to show that there cannot be too many such honest blocks, i.e., most of the honest blocks do contribute to safety.

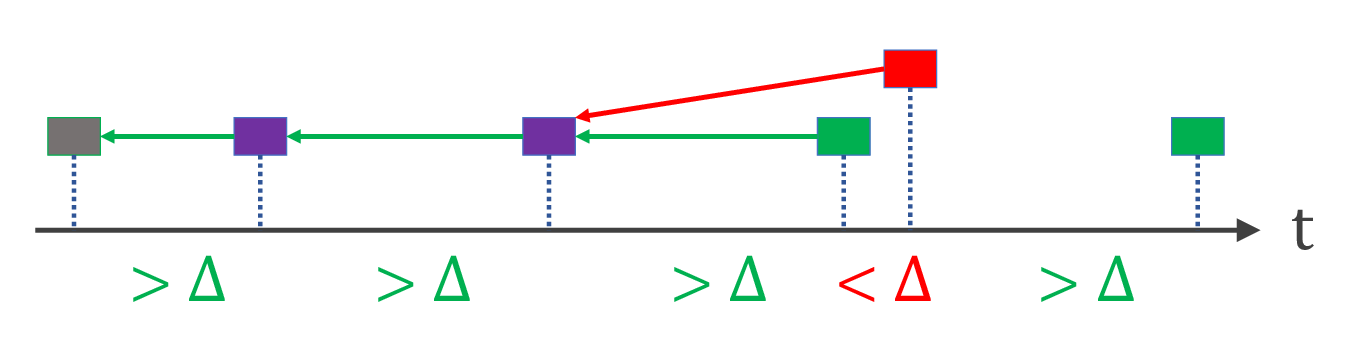

How do we rigorously define whether or not a block contributes to safety? This brings us to a central notion in the proof: tailgating. For now, let us pretend there is no adversary for simplicity. When would two honest blocks not extend one another? The only case is that they are mined too closely to each other. How close is too close? You guessed it, within $\Delta$ time! To elaborate, if two blocks are mined less than $\Delta$ time apart, then the latter one may not be aware of the former one, and we call the latter block a tailgater.

The illustration below shows tailgaters in red and non-tailgaters in green and purple. (The difference between green and purple will be explained further later.)

Formal proof sketch

Let us put all honest blocks on a time axis based on when they are mined. (The definitions/lemmas/theorems are numbered to match the paper).

Definition 4(i). Suppose an honest block $B$ is mined at time $t$. If no other honest block is mined between time $t-\Delta$ and $t$, then $B$ is a non-tailgater (otherwise, $B$ is a tailgater).

Non-tailgaters have a nice property:

Lemma 5(i). Non-tailgaters do not have the same height.

The proof is rather straightforward. Since the two blocks do not tailgate one another, the block mined later is aware of the block mined earlier. Thus, the later block will at least be attempted at a height higher than the earlier block (longest chain wins). Note that the proof holds no matter what the adversary does.

Now an important question is: what fraction of honest blocks are tailgaters vs. non-tailgaters? This turns out to be a well-known result for Poisson processes. The gap time $T$ between two blocks (also called the inter-arrival time between two events) follows an i.i.d. exponential distribution with the same rate (in this case $\alpha$): $\Pr[T>s] = e^{-\alpha s}$. Plugging in $\Delta$ and let $g=e^{-\alpha\Delta}$ for short, each honest block is a tailgater with probability $1-g$ and is a non-tailgater with probability $g$.

Congratulations if you are still following! We have pretty much completed the liveness proof. Note that, in expectation, the number of non-tailgaters grows at a rate of $g\alpha$. Also note that non-tailgaters all have different heights (Lemma 5(i)), so the longest chain grows at least at the rate of non-tailgaters. QED liveness. The proof in the paper needs extra rigor to take care of some technical details, e.g., proving that the actual outcome is unlikely to deviate much from the expected outcome. But all the main ideas are as presented above.

Non-tailgaters helped us prove liveness. To prove safety, we need to introduce an even nicer type of blocks: loners

Definition 4(ii). Suppose an honest block $B$ is mined at time $t$. If no other honest block is mined between time $t-\Delta$ and $t+\Delta$, then $B$ is a loner.

Lemma 5(ii). A loner is the only honest block at its height.

In other words, a loner is an honest block that does not tailgate and is not tailgated. Loners are shown in purple in the previous figure. A loner has the nicer property of Lemma 5(ii). The proof is identical to Lemma 5(i); simply note that a loner and any other honest block do not tailgate one another by definition.

In order to violate safety, there needs to be two chains that diverge by more than $k$ blocks, both adopted by honest nodes. Let us consider the time window in which these two diverging chains are mined. In this window, there has to be more malicious blocks than loners. This is because we can pair each loner with a malicious block: a loner does not share height with other honest blocks (Lemma 5(ii)), so one of the two blocks at that height must be a malicious block. To summarize, in order to violate safety, there must be a period of time during which the adversary mines more blocks than honest nodes mine loners. In other words, if honest nodes can mine loners faster than the adversary can mine blocks, then safety violation is unlikely to occur.

The adversary mines blocks at a rate $\beta$. What is the rate at which honest nodes mine loners? A loner requires two back-to-back non-tailgaters, so the expected loner rate should be $g^2 \alpha$. Again, the actual proof needs some extra rigor to deal with details such as actual vs. expected outcomes but the main ideas are all there. Therefore, we conclude:

Main Theorem (informal). Nakamoto consensus guarantees safety and liveness if $g^2 \alpha >\beta$.

This final condition $g^2 \alpha > \beta$ has a clear interpretation. It is the honest majority assumption after taking into account network delay. $g=e^{-\alpha\Delta}$ (and $g^2$) can be thought of as the loss in honest mining rate due to network delay. Most people intuitively understand why Bitcoin has a large block interval (e.g., 10 min). Hopefully this proof gives a more principled way to understand this fact. If the block interval is much larger than the network delay, which implies $\alpha\Delta \approx 0$, then $g \approx g^2 \approx 1$, and Nakamoto consensus is safe as long as we have honest majority. If the block interval is very small, say comparable to $\Delta$, then $\alpha\Delta$ is noticeably larger than 0, $g$ is noticeably smaller than 1, and accordingly, the fault tolerance of Nakamoto consensus noticeably worsens.