In this series of three posts, we discuss two of the most important consensus lower bounds:

- Lamport, Fischer [1982]: any protocol solving consensus in the synchronous model that is resilient to $t$ crash failures must have an execution with at least $t+1$ rounds.

- Fischer, Lynch, and Patterson [1983, 1985]: any protocol solving consensus in the asynchronous model that is resilient to even one crash failure must have an infinite execution.

The modern interpretation of these lower bounds highlights the importance of randomness:

- Bad news: Without randomness, asynchronous consensus is impossible, and synchronous consensus is slow.

- Good news: With randomness, consensus (both in synchrony and in asynchrony) is possible in a constant expected number of rounds. Randomness does not circumvent the lower bounds; it just reduces the probability of bad events implied by the lower bounds. In synchrony, the probability of slow executions can be made exponentially small. In asynchrony, termination happens almost surely. Formally, the probability measure of the complement of the event of terminating in some finite number of rounds is zero.

The plan: three posts

-

In this first post, we provide key definitions and prove an important Lemma about having some initial uncommitted configuration. This lemma shows that any consensus protocol has some initial input where the adversary has control over the decision value (it can cause it to be either 0 or 1). This lemma will then be used in both lower bounds.

-

In the second post, we use the approach of Aguilera and Toueg [1999] to prove that any protocol solving consensus in the synchronous model that is resilient to $t$ crash failures must have an execution with at least $t+1$ rounds. The proof uses the definitions and the lemma in this post.

-

In the third post, we prove the celebrated Fischer, Lynch, and Patterson [1985] result that any protocol solving consensus in the asynchronous model that is resilient to even one crash failure must have an infinite execution. The proof uses the same definitions and the lemma in this post.

Definitions

The goal: Binary Agreement with crash failures

There are $n$ parties. Each party is a state machine that has some initial input $\in {0,1}$. The state machine has a special decide action that irrevocably sets its decision $\in {0,1}$.

We say that a protocol $\mathcal{P}$ solves agreement against $t$ crash failures if in any execution with at most $t$ crash failures:

- Termination: all non-faulty parties eventually decide.

- Agreement: all non-faulty parties decide on the same value.

- Validity: if all non-faulty parties have the same input value, then this is the decision value.

Parties as State Machines

We model each party as a deterministic state machine, and model randomness by giving the state machine read-only access to a tape of random bits. Each state machine has access to an immutable input register, a read-only incoming-messages queue, and a write-only outgoing-messages queue. At any given moment, the local state of a party is fully defined by the state of its state machine and the content of it input register and local message queues. A protocol, $\mathcal{P}$, for $n$ parties is a set of $n$ state machines.

Message passing

When a party wishes to send a message $m$ to a recipient party $p$, it locally writes $(m,p)$ on its outgoing-messages queue. The system then adds this event $e=(m,p)$ to a global set of pending messages. Once an event enters the pending messages set, the adversary can decide when to deliver the event (with some constraints that depend on the network model: synchrony or asynchrony). When event $e=(m,p)$ is delivered, the system adds the message $m$ to the local incoming-messages queue of party $p$.

Configuration

Given a protocol $\mathcal{P}$, a configuration of a system is just the state of all the parties and the set of all pending, undelivered messages. More formally, a configuration $C$ is a vector of local states and a set $C_M$ of pending messages. We say that $e\in C_M$ is a pending message and $e=(m,p)$ if the configuration $C$ has a pending message $m$ sent to a party $p$ that party $p$ did not receive yet.

Initial Configuration

Given a protocol $\mathcal{P}$, the initial configuration of the system is fully described by the vector of inputs.

Deciding Configuration

$C$ is a deciding configuration: if all non-faulty parties have decided in $C$. We say that $C$ is 1-deciding if the common decision value is 1, and similarly that $C$ is 0-deciding if the decision is 0.

Note that it’s easy to check if a configuration is deciding - just look at the local state of each non-faulty party.

Committed Configuration (informal)

The goal of a consensus protocol is for the system to eventually reach a deciding configuration (despite the adversary’s control of the asynchrony and ability to corrupt parties). The magic moment (sometimes called the “commit point”) of any consensus protocol is when the system reaches a committed configuration. This is a configuration where no matter what the adversary does from this point onwards, the eventual decision value is already fixed. Note that there is no obvious externally observable way to know if a configuration is indeed a committed configuration or is still uncommitted. In particular, parties need to learn that they are in a committed configuration before they decide.

We choose to use new names to these definitions, which we feel provide a more intuitive and modern viewpoint. The classical name for a committed configuration is univalent configuration and for an uncommitted configuration is bivalent configuration.

Transitioning from one configuration to another

We write $C \rightarrow C’$: If in configuration $C$ there exists a time interval $T$ and a pending message $e$ (or all undelivered messages $E$ in the synchronous model) such that configuration $C$ changes to configuration $C’$ by processing all local parties for $t$ time and then delivering $e$ (or delivering all $E$ in the synchronous model). When a pending message $e=(m,p)$ is delivered, then party $p$ receives message $m$ in its incoming-messages queue.

We write $C \xrightarrow{T, e=(p,m)} C’$ when we are explicit about the event $e$ causing the transition, and write $C \xrightarrow{e=(p,m)} C’$ when $T=0$ and $C \xrightarrow{T} C’$ when only $T$ time passes.

The differences between $C$ and $C’$ are:

- The local state of party $p$ includes the message $e$;

- The set of pending messages $C’_M$ of configuration $C’$:

- $e$ is removed from $C’_M$;

- $C’_M$ may contain new messages that are sent by parties while processing for $T$ time.

Observe that the local state of any party that is not $p$ is exactly the same in $C \xrightarrow{T} C’’$ and in $C \xrightarrow{T,e=(p,m)} C’$.

We write $C \rightsquigarrow C’$: If there exists a sequence $C = C_1 \rightarrow C_2 \rightarrow \dots \rightarrow C_k=C’$ ($\rightsquigarrow$ is the transitive closure of $\rightarrow$).

For a sequence of delays and events $\pi=T_1,e_1,\dots,T_{k}, e_{k}$ we write $C \stackrel{\pi}{\rightsquigarrow} C’$.

Discussion: Note that in FLP JACM 85 a step is defined as a receiving of an event $e$ and immediately sending a finite set of messages. This model does not explicitly allow using timeouts or sending an unbounded number of messages over time. We assume a global clock model and model a step as first an amount of global time $T$ that passes and then the receiving event $e$. This explicitly captures the use of timeouts. Note that this means that during a transition $C \xrightarrow{T} C’’$ the state of all parties may change and the proof needs to take this into account when arguing for indistinguishability.

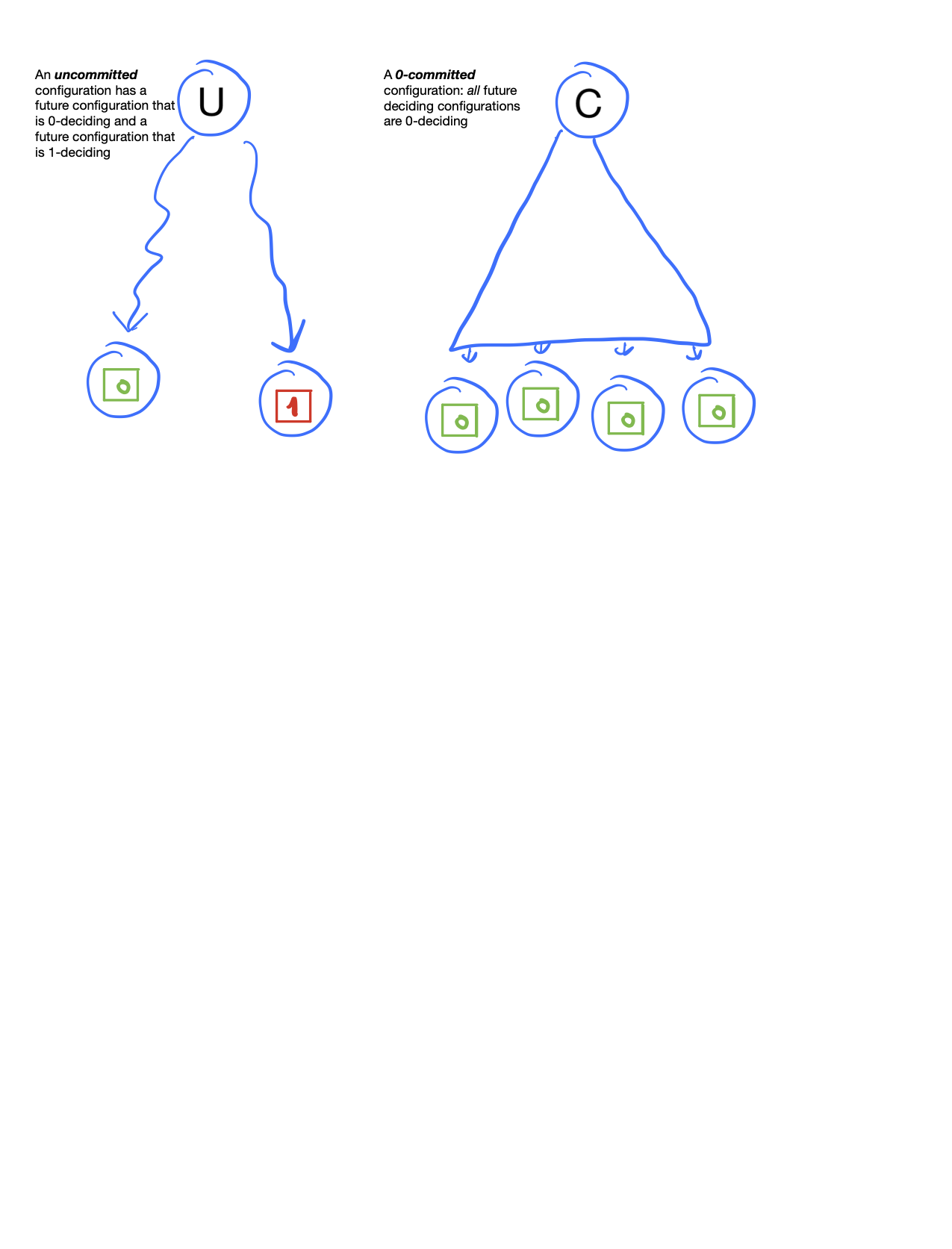

Uncommitted Configuration

$C$ is an uncommitted configuration: if it has a future 0-deciding configuration and a future 1-deciding configuration. There exists $C \rightsquigarrow D_0$ and $C \rightsquigarrow D_1$ such that $D_0$ is 0-deciding and $D_1$ is 1-deciding.

Said differently, an uncommitted configuration is a configuration where the adversary still has control over the decision value. There are some adversary actions (crash events, message delivery order) that will cause the parties to decide 0 and some adversary actions that will cause the parties to decide 1.

An uncommitted configuration is a state of a system as a whole, not something that can be observed locally. Note that there is no simple way to know if a configuration is uncommitted. It requires examining all the possible future configurations (all possible adversary actions).

Committed Configuration

$C$ is a committed configuration: if every future deciding configuration $D$ (such that $C \rightsquigarrow D$) is deciding on the same value. We say that $C$ is 1-committed if every future ends in a 1-deciding configuration, and similarly that $C$ is 0-committed if every future ends in a 0-deciding configuration.

Said differently, a committed configuration is a configuration where the adversary has no control over the decision value. When a configuration is committed to $v$, no matter what the adversary does, the decision value will eventually be $v$.

Note that there is no simple way to know if a configuration is committed or uncommitted. In particular, there is no local indication in the configuration, and it may well be that no party knows that the configuration is committed.

The existence of an initial uncommitted configuration

With these definitions, we can re-state the validity property as:

Validity: if all non-faulty parties have the same input $b$ then that initial configuration must be $b$-committed.

Are all initial configurations either 1-committed or 0-committed? The following lemma shows that this is not the case: every protocol that can tolerate even one crash failure must have some initial configuration that is uncommitted.

Lemma 1 (Lemma 2 of FLP85): If $\mathcal{P}$ solves agreement against at least one crash failure, then $\mathcal{P}$ has an initial uncommitted configuration.

A recurring proof pattern for showing the existence of an uncommitted configuration will appear many times in these three posts. We start by stating it in an abstract manner:

- Proof by contradiction: assume all configurations are either 1-committed or 0-committed.

- Define a notion of local adjacency that differ by just one party. Find two adjacent configurations $C$ and $C’$ such that $C$ is 1-committed and $C’$ is 0-committed.

- Reach a contradiction due to an indistinguishability argument between the two adjacent configurations $C$ and $C’$. The adjacency allows the adversary to cause indistinguishability via crashing of just one party.

Proof of the Lemma 1 follows the proof pattern above:

- Seeking a contradiction, assume there is no initial configuration that is uncommitted. So all initial configurations are either 1-committed or 0-committed.

- Define two initial configurations as $i$-adjacent if the initial value of all parties other than party $i$ are the same. Consider the sequence (or path) of $n+1$ initial configurations: $(1,\dots,1),(0,1,\dots,1),(0,0,1,\dots,1),\dots,(0,\dots,0,1), (0,\dots,0)$. By the validity property, the leftmost is 1-committed and the rightmost is 0-committed. So there must be some party $i$ such that the two $i$-adjacent configurations $C,C’$ are 1-committed and 0-committed, respectively.

- Now consider in both configurations $C$ and $C’$ the execution where party $i$ crashes right at the start of the protocol. We now have two configurations $\hat{C}, \hat{C’}$. Observe that these two configurations are indistinguishable for all non-faulty parties. So the non-faulty parties must decide the same value in any future of $\hat{C}$ and $\hat{C’}$. This is a contradiction to the assumption that $C$ is 1-committed and $C’$ is 0-committed.

This proves that any protocol $\mathcal{P}$ must have some initial uncommitted configuration. The next two posts will use the existence of an initial uncommitted configuration and extend it to more rounds!

Proof by example for n=3: For $n=3$ parties consider the 4 initial configurations $(1,1,1), (0,1,1),(0,0,1),(0,0,0)$. By validity, configuration $(1,1,1)$ must be 1-committed and configuration $(0,0,0)$ must be 0-committed. Seeking a contradiction, let’s assume none of the 4 initial configurations is uncommitted. So both $(0,1,1)$ and $(0,0,1)$ are committed. Since all 4 initial configurations are committed there must be two adjacent configurations that are committed to different values. Without loss of generality, assume that $(0,1,1)$ is 1-committed and $(0,0,1)$ is 0-committed. Now suppose that in both configurations, party 2 crashes right at the start of the protocol. Observe that both configurations look like $(1,CRASH,0)$. So both executions must decide the same, but this is a contradiction because one is 1-committed and the other is 0-committed.

Minimal validity condition

Note that all this proof required was the existence of one 1-committed initial configuration and one 0-committed initial configuration.

Acknowledgment

Many thanks to Kartik Nayak for valuable feedback on this post.

Please leave comments on Twitter