In this two-part post, we focus on the challenges and subtleties involved in obtaining privacy in private proof-of-stake (PoS) blockchains. For instance, designs that attempt to obtain privacy for transaction details while still relying on PoS, such as Ouroboros Crypsinous. The first part explains attacks on existing approaches, and the second part focuses on potential workarounds using differential privacy. These posts explain the intuitive ideas behind the works of Madathil et al. (IEEE S&P ‘21) and Wang et al. (Usenix Security ‘23).

Through Bitcoin, Nakamoto first introduced a permissionless protocol where any party can join (as a block producer) the protocol without requiring any explicit permission. To tolerate a large number of adversarial parties, Bitcoin relies on the use of constrained resources, namely, computation in the form of proof-of-work, to determine parties who are allowed to contribute (“leaders”) to the blockchain. The protocol is secure assuming the amount of computing power (a type of constraint resource) invested by honest parties exceeds that by the Byzantine parties. However, there are two key concerns with the protocol used by Bitcoin.

- First, due to the use of compute power to elect leaders in the protocol, Bitcoin burns a lot of energy in the process.

- Second, in Bitcoin, all transactions are publicly available to everyone.

Addressing energy-efficiency using proof-of-stake (PoS). The use of proof-of-stake can help address the energy concern. PoS protocols offer an energy-efficient design that leverages constraints on stakes held by parties in the system. Typically, it is assumed that at least $\frac{2}{3}$ of the total stake is held by honest parties, which is equivalent to saying that the fraction of corrupted parties, $f$, is less than $\frac{1}{3}$. Protocol participants are chosen through private lotteries in which each party’s winning odds are proportional to the stake they possess.

Addressing privacy constraints using cryptography. The open setup of blockchains makes the privacy of transactions a crucial concern. As such, private blockchains have been proposed with the idea to conceal transaction details using advanced cryptographic primitives while utilizing zero-knowledge proofs to validate transactions and ensure the proper functioning of the protocol. Although there are a few private blockchain systems, such as Zcash, that have been successfully implemented and are currently in use, they are built on the Proof-of-Work (PoW) architecture.

Can we obtain both privacy and energy efficiency simultaneously? In other words, can we obtain privacy in a proof-of-stake blockchain system?

A natural approach to answer this question is to adapt the approach to privacy in a PoW system to a PoS system. However, in a PoS system, the stake itself is a sensitive property. Thus, disclosing the exact stake owned by a party can inadvertently expose transaction details to potential attackers. For instance, the transaction outcomes between any two time steps can be inferred, as the stake represents the additive outcome of a sequence of transactions.

A primary measure by which one can infer a party’s stake is by knowing the number of times a party is elected as a participant on the chain. Thus, privacy-preserving PoS protocols such as Kerber et al. and Ganesh et al. attempt to hide the participants by using anonymous VRFs; at a high level, these VRFs prove that a party that presents a token (VRF output) has been elected to participate but do not reveal who the party is. The works claim that so far as these messages are sent through anonymous broadcast channels, both the transaction values and stake values would be hidden.

Does the use of anonymous VRFs suffice to obtain privacy?

To answer this question, there are two key aspects of private PoS protocols that we should know about. First, despite the privacy guarantees, in any protocol, the sender of a transaction will need to know whether the transaction has been committed. This is necessary for the functioning of any blockchain protocol. This allows the adversary to obtain a mapping between a transaction it created and the block in which it was added. Second, any message sent by an honest party may take up to a $\Delta$ time to be received by all honest parties. If an adversary can delay messages within the $\Delta$ time, then perhaps it can cause different parties to have different views of the state of the system and then use the first observation to identify whether a party has been elected to participate.

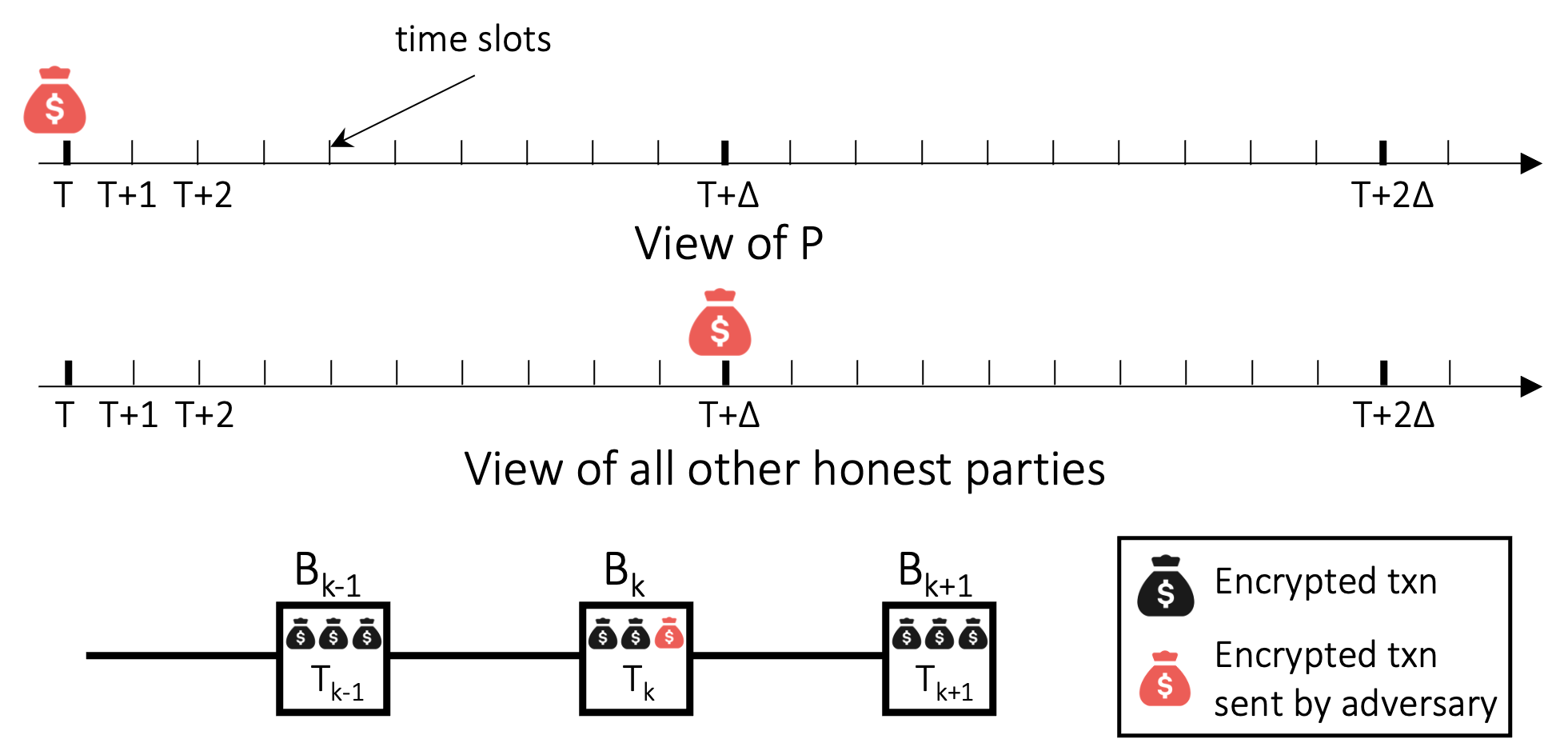

Specifically, the adversary can perform the following attack where it is trying to judge the frequency with which a party $P$ proposes a block compared to the rest of the network; this frequency is directly related to $P$’s stake. The adversary sends a transaction $tx$ (denoted by the red bag of money) to a party $P$ at time $T$ but delays sending this transaction to other parties until time $T+\Delta$. Thus, if a block containing $tx$ is produced during this $\Delta$ time duration, then it must be the case that $P$ produced it. Moreover, due to our first observation, the adversary knows that a specific block contains $tx$. Such an attack suffices for an adversary to estimate the stake of a party, something that privacy-preserving protocols attempt to hide.

Can we actually achieve such an adversarial delay of messages? Yes! Miller et al. proposed an attack technique, namely the InvBlock attack. At a high level, the attacker creates a transaction $tx$ and sends it to the victim node. To the victim’s peers, it immediately sends the transaction hash but withholds the transmission of the transaction body. This action prompts the peers to wait for the transaction body from the attacker until a timeout is reached. This causes a necessary difference in views between the victim and all other parties in the network.

Detailing Privacy Attacks on Private PoS Blockchains

In the last section, we showed that the state-of-the-art approaches that rely on anonymous Verifiable Random Functions (VRF) are insufficient in safeguarding stake privacy. Certain privacy attacks exist that enable an attacker to gain information related to the stake owned by a particular party. In this section, we will elaborate on this concept to show specific attacks. These attacks were presented by the works of Madathil et al. and Wang et al.

Comparing an unknown stake value with a known threshold. The first attack by Madathil et al. allows the adversary to tag a specific (honest) party with unknown stake and subsequently compare this unknown stake value against an adversary-selected threshold. The attack is called Reverse tagging attack (RTA), which exploits the (deterministic) liveness requirement ensured by the underlying blockchain

$( z , t )$-liveness: For any transaction $\mathsf{tx}$ that is input to at least $z$ fraction of the honest parties, it must get confirmed after $t$ time steps.

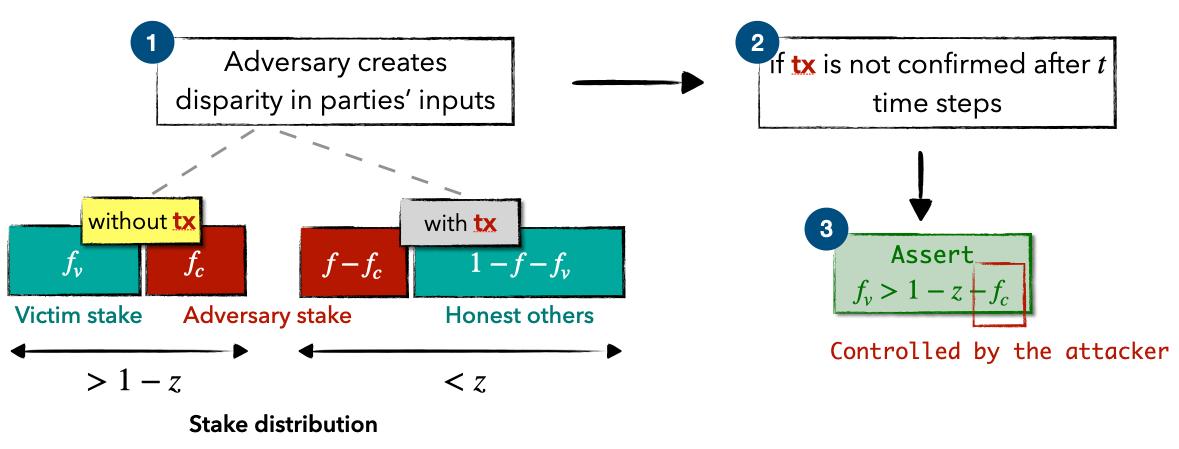

In this attack, we start by splitting all participants into two groups. The first group, let’s call it G1, includes the victim and some corrupted parties chosen by the adversary. These chosen parties have a total stake equal to $f_c$ (a value chosen by the adversary). The second group, G2, contains all remaining parties.

Next, the adversary aims to create a disparity in the inputs of these two groups. Specifically, the attacker generates a transaction that is received by all in G2 but is not received by anyone in G1. This can be achieved by using the InvBlock primitive to delay a self-created transaction, ensuring the transaction is absent from the target node and the selected corrupted nodes (as a result parties holding stakes totaling $f_c+f_v$ that do not receive this transaction).

Finally, the adversary just waits for $t$ time units to see if the transaction is confirmed. If it is not confirmed, one can conclude that the stake of the victim $f_v$ must exceed $1-z-f_c$, as per the definition of liveness. The following figure shows an abstracted flow of this attack.

A limitation of this approach, though, is that RTA is only effective under deterministic protocols that satisfy stringent liveness conditions, e.g., guaranteeing the inclusion of a block within a given time window.

Approximating an unknown stake value. Recently, Wang et al. proposed an improved stake inference attack (SIA) that efficiently approximates an unknown stake value. Moreover, this attack also captures randomized protocols with probabilistic liveness.

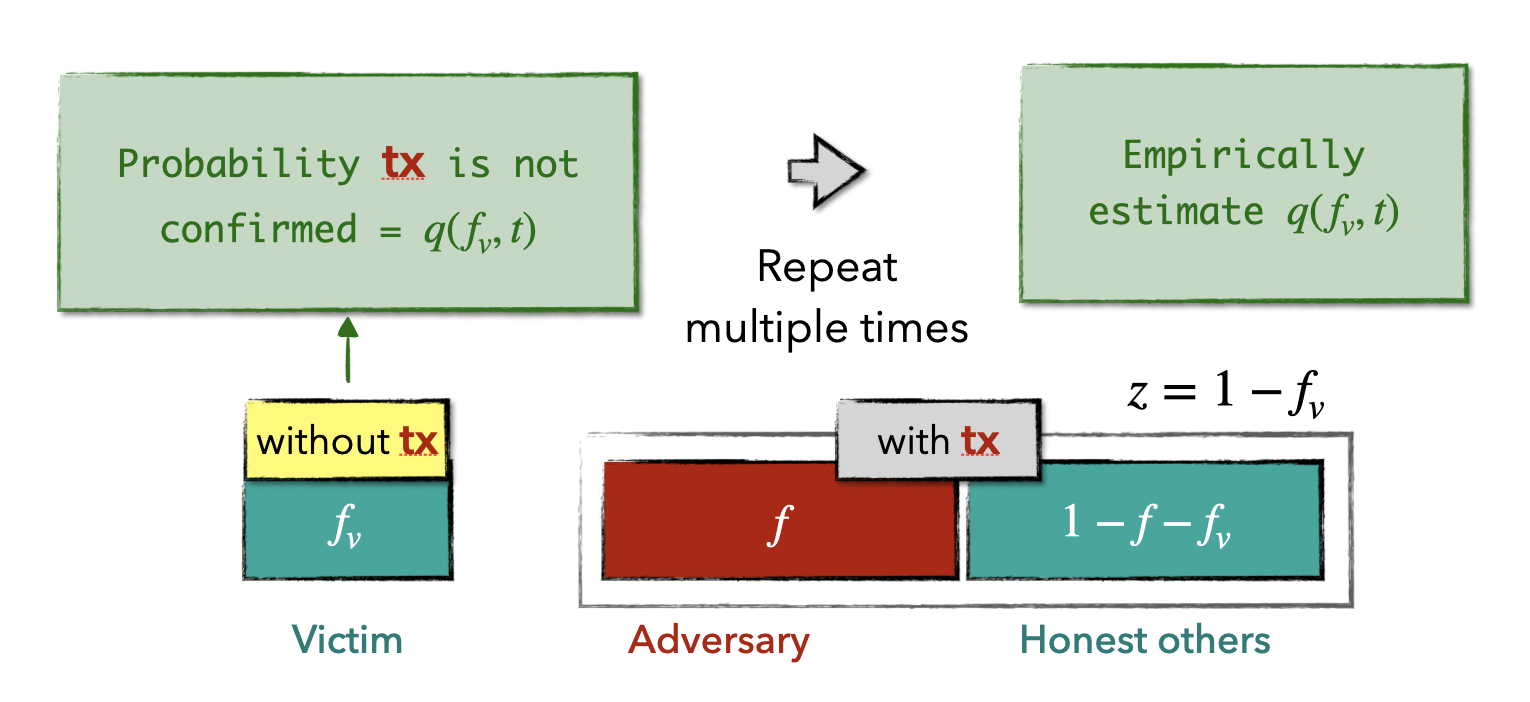

Probabilistic $( z , t )$-liveness: For any transaction $\mathsf{tx}$ that is input to $z$ fraction of the honest parties, the probability $\mathsf{tx}$ is NOT confirmed after $t$ time steps equals to $q(1-z,t)$, where $q(\cdot)\in(0,1)$ is a strictly increasing linear function related to the first input (i.e., $1 - z$).

Based on the aforementioned liveness definition, we know that if there’s a transaction, let’s say $tx$, that is missing from the transaction pool of a victim node (with stake $f_v$) but has been received by all others, then the probability of $tx$ remaining unconfirmed after $t$ time steps equals $q(f_v, t)$. This probability is directly tied to the victim’s stake, thereby providing the attacker with an interface to exploit $f_v$. Due to the randomness involved in the protocol, it’s typically challenging to directly calculate the actual value of $q(1-z,t)$. However, it can be assessed empirically, i.e., by repeatedly launching the delay primitive. The subsequent figure presents an abstracted workflow.

Even though it’s possible to estimate $q(f_v, t)$, computing the pre-image $f_v$ still poses a significant challenge. We examine a search approach to locate an approximated pre-image close to $f_v$. To elaborate, the adversary selects a subset of compromised nodes with a stake of $f_c$ and compares $q(f_c, t)$ with $q(f_v,t)$. Then, the adversary adaptively updates $f_c$ to to minimize the difference $|q(f_c, t) - q(f_v, t)|$ until certain termination condition is triggered. The adversary then reports the final $f_c$ as an approximation of $f_v$. Please note that various search strategies can be applied here, in the following, we propose a strategy based on a binary search tree, which offers sublinear execution time.

First, we establish a balanced search tree with $n$ leaf nodes, each labeled with a stake segment. Specifically, the root is labeled with [0,f], and every internal node represents the integral stake segment of its child. Beginning at the root node, we traverse the search tree until we hit a leaf node such that the corresponding search coins denoted by the stake segments, contains the target coin. Unlike traditional binary search, when deciding the branch, we need to compare two probabilities instead of comparing two concrete values. By hoeffding’s inequality, with $O(\log\log n)$ many coin flips, one can compare two coins with at most $\frac{1}{\log n}$ failure probability. Note that, the search has at most $\log n$ branch selection, thus by union bound, the overall failure probability is constant. And the total running time is sub-linear.

Acknowledgment. We would like to thank Ittai Abraham and Ashwin Machanavajjhala for their feedback on this post.

Please post your comments on Twitter.