The Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) developed by Cooley and Tukey in 1965 has its origins in the work of Gauss. The FFT, its variants and extensions to finite fields, are a fundamental algorithmic tool and a beautiful example of interplay between algebra and combinatorics. There are many great resources on FFT, see ingopedia’s curated list.

Given a field $F$, a polynomial of degree at most $d-1$ is defined as $P(X)=a_0+a_1 X+ \dots + a_{d-1} X^{d-1}$, where each $a_i \in F$. $P(X)$ can be viewed as a vector $\vec{a}=\langle a_0,\dots,a_{d-1} \rangle$ of $d$ elements in $F$.

Polynomials can also be evaluated. Given $d$ unique points $x_1,\dots,x_d$ in $F$, we can represent $P(X)$ as the vector $\vec{y}=\langle y_1,\dots,y_d \rangle$, where $y_i=P(x_i)$ is the evaluation of $P(X)$ on $x_i$.

In a previous post we showed the isomorphism $\vec{a} \leftrightarrow \vec{y}$ between degree at most $d-1$ polynomials and their evaluations at $d$ unique points. Here we focus on the computational cost of this mapping: the number of field operations.

Given $\vec{a}$ for a polynomial of degree at most $d-1$, one can compute each $y_i=P(x_i)$ using Horner’s method via $O(d)$ field operations (observing that $P(X)=a_0+x(a_1+(x(a_2 + \dots + )))$ ). For a total of $O(d^2)$ operations to compute $\vec{y}$. Can we compute the evaluation $\vec{a} \to \vec{y}$ in better than quadratic?

Similarly, for $d$ unique points $\vec{x}$, it is possible to compute the $i$-th Lagrange base polynomial $L_i(X)$ which equals 1 on $x_i$ and 0 for all $x_j, j \neq i$ using $O(d)$ operations as $L_i(X)= \prod_{j \neq i} (X-x_j)/ \prod_{j \neq i} (x_i-x_j)$. So given evaluations $\vec{y}$, computing $P(X)= \sum_{i=1}^d y_i L_i(X)$ can be done in $O(d^2)$ operations. Can we compute the interpolation $\vec{y} \to \vec{a}$ in better than quadratic?

The Fast Fourier Transform allows interpolating and evaluating a polynomial on special points, roots of unity, with $O( d \log d)$ operations.

FFT Theorem:

- Given $d=2^D$ and a field $F$ of characteristic $p=qd+1$, let $\omega$ be a primitive $d$-th root of unity. There exists as algorithm that in $O(d \log d )$ operations:

- Computes $P(\omega^0),\dots,P(\omega^{d-1})$ given the coefficients of a degree at most $d-1$ polynomial $P(X)$.

- Computes the coefficients of the degree at most $d-1$ polynomial $P(X)$ given $d$ evaluations $P(\omega^0),\dots,P(\omega^{d-1})$.

This result uses two powerful ingredients: divide-and-conquer, and roots of unity. We start with the first direction: computing the evaluations given the coefficients.

The first ingredient: decompose a polynomial into its odd and even coefficients each with half the degree

Assume that $P(X)$ has degree at most $d-1$ and that $d=2^D$ is a power of two. A classic divide-and-conquer algorithm design principle when applied to polynomials is to “split” a degree at most $d-1$ polynomial into two degree at most $d/2-1$ polynomials by dividing the polynomial to its even and odd coefficients:

\[P(X)= P_e(X^2) + XP_o(X^2) \label{\star} \tag{*}\]Where $P_e(X),P_o(X)$ are polynomials induced by the even and odd coefficients of $P(X)$ as follows:

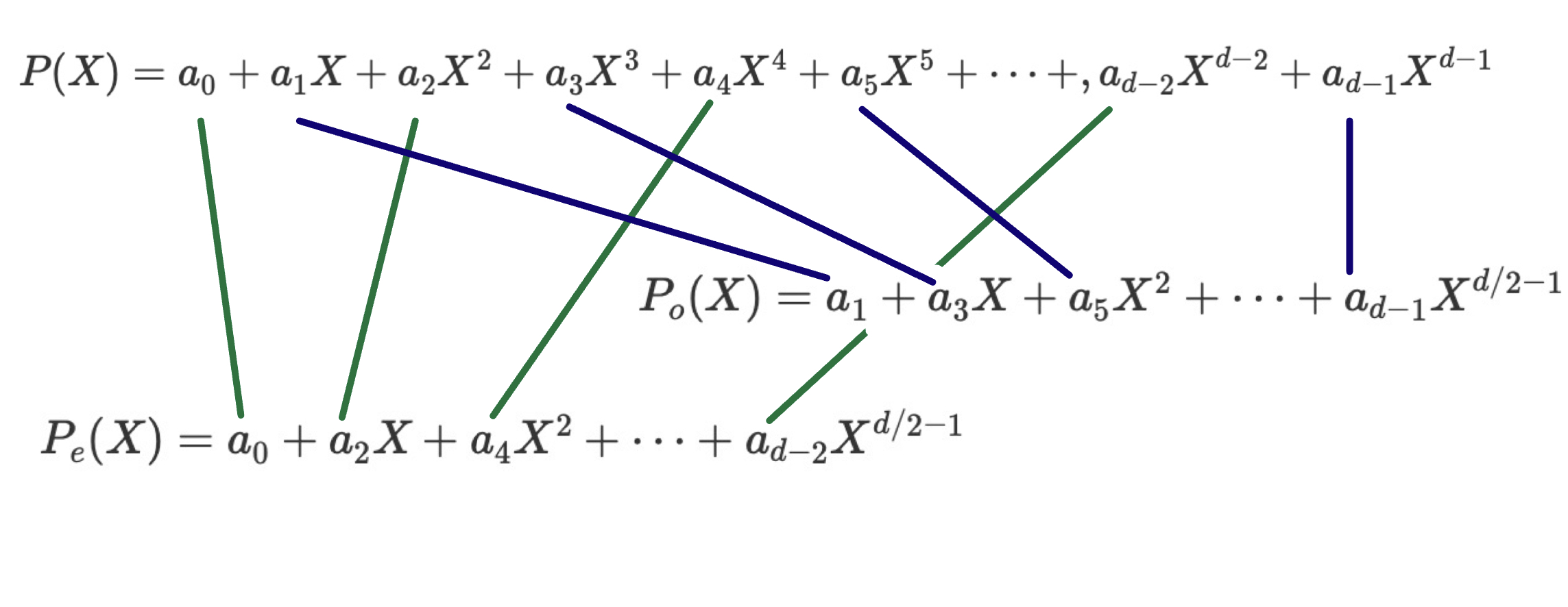

\[P_e(X)=a_0 + a_2 X+ a_4 X^2 + \dots+ a_{d-2}X^{d/2 -1}\] \[P_o(X)=a_1 + a_3 X+ a_5 X^2 + \dots+ a_{d-1}X^{d/2 -1}\]Here is a pictorial representation of the odd and even indexes:

Why is this such a powerful divide-and-conquer decomposition?

- Given $d$ evaluations $P_e(a_1^2),\dots,P_e(a_{d}^2)$ and $d$ evaluations $P_o(a_1^2),\dots,P_o(a_{d}^2)$, one can compute the desired $d$ evaluations $P(a_1),\dots,P(a_d)$ in $2d$ operations, simply because $P(a_i)=P_e(a_i^2) + a_i P_o(a_i^2)$ via $(\ref{\star})$.

- The degree of $P_e(X)$ and $P_o(X)$ is at most $d/2-1$. So if we manage to repeat this recursion we can get $O(\log d)$ depth!

- However, to continue recursively there seems to be a challenge:

- $P_e(X)$ and $P_o(X)$ are of degree less than $d/2$, so from the recursion, we are given only $d/2$ (not $d$) evaluations $P_e(b_1),\dots,P_e(b_{d/2})$ and similarly $d/2$ (not $d$) evaluations for $P_o(X)$.

- However, to compute all $d$ evaluations of $P(X)$ via $(\ref{\star})$ we need the $d$ evaluations $P_e(a_0^2),\dots,P_e(a_{d}^2)$ and similarly the $d$ evaluations of squares for $P_o(X)$.

- How can we generate $d$ evaluations of squares from just $d/2$ evaluations using $O(d)$ operations?

The second ingredient: use roots of unity

For $g \in F$, if $g^d=1$ then we call $g$ a $d$-th root of unity. Moreover, if $g^1,\dots,g^d$ generates $d$ distinct elements then we call $g$ a primitive $d$-th root of unity.

Suppose $g$ is such a primitive $d$-th root of unity. So $g,g^2,\dots, g^{d-1}, g^d=1$ forms a cyclic group of order $d$ with $d=2^D$.

Now, if we start squaring these roots of unity, we can see a pretty cool pattern. Starting at the first elements, we get:

\[(g^1)^2=g^2,(g^2)^2=g^4,...,(g^{d/2-1})^2=g^{d-2},(g^{d/2})^2=g^{d}=1\]Since we got to the value $1$ at the $d/2$-th power, elements now start repeating!

\[(g^{d/2+1})^2=g^{d+2}=g^d\cdot g^2=g^2,(g^{d/2+2})^2=g^4,...,(g^{d})^2=g^{d}=1\]So we can solve the challenge above:

- Evaluate $P_e(X)$ and $P_o(X)$ at the $d/2$ points $g^2,g^4, \dots, g^{d}=1$ that form the cyclic group of order $d/2$ of the $d/2$-th roots of unity. Repeating this sequence twice gives us $d$ evaluations at the squares of the cyclic group of order $d$. Each member of $d/2$ appears twice in the squares of $d$:

The $d/2$ evaluations of the $d/2$-th roots, repeated twice, give all the $d$ evaluations of squares of the $d$-th roots. This was the missing piece to complete the divide-and-conquer!

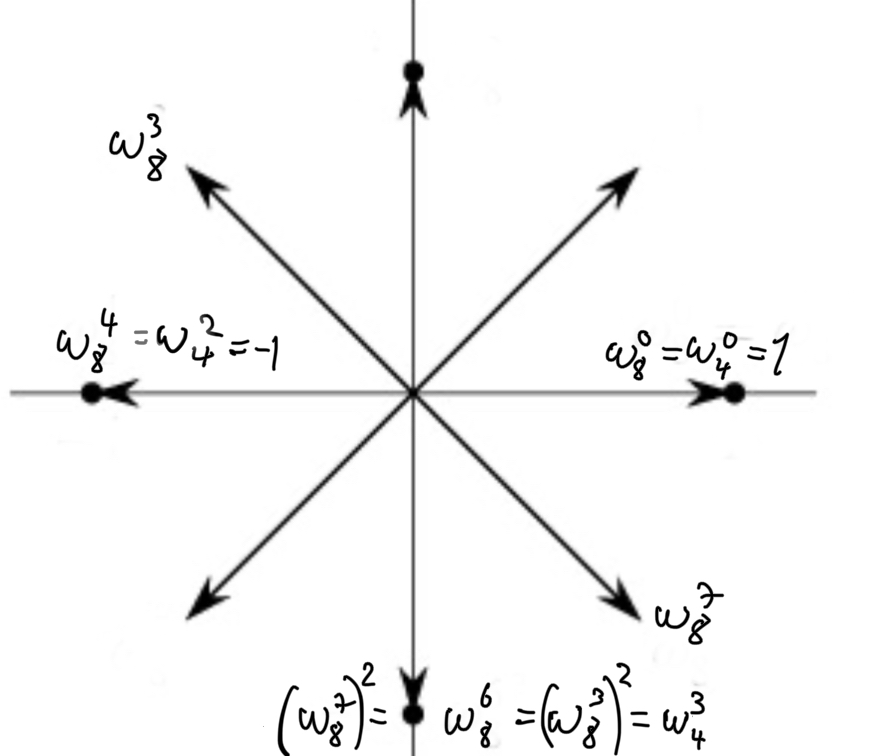

As a visual example, fix $d=8$, every square of a power of $\omega_8$, say $(\omega_8^i)^2$ equals a power of $\omega_4$ (in particular $\omega_4^{i \bmod 4}$). For a specific example consider the squares of $\omega_8^3$ and $\omega_8^7$. Observe that $(\omega_8^3)^2 = \omega_8^6 = \omega_4^3$ and similarly $(\omega_8^7)^2 = \omega_8^{14} = \omega_8^{6} = \omega_4^3$:

Finding a primitive root of unity

If $F$ is a prime Field of characteristic $p=dq+1$ then we are guaranteed that for any $x$, $g=x^q$ is a $d$-th root of unity because $g^d = x^{qd}=x^{p-1}=1$ (using Fermat’s little theorem). It is easy to check that the $d$-th roots of unity form a multiplicative group, and hence a cyclic group.

Choosing $x$ uniformly at random from $F\setminus {0}$ we get that $x^q$ is a uniformly random $d$-th roots of unity.

To see why this is true, denote $f(x)=x^q$ and see that $|x \text{ s.t. } f(x)=y|=q$ for all $y$. Indeed $f(x)$ maps a set of size $dq$ to a set of size at most $d$ (since $f(x)^d=1$ is a root of $x^d -1$ which can have at most $d$ roots). Finally, for any $y$ there can be at most $q$ values such that $x^q=y$. So $f(x)$ must map exactly $q$ elements to each of the $d$ options. Here we used twice the fundamental fact that nontrivial polynomials cannot have more roots than their degree.

Since $d=2^D$, the cyclic group of order $d$ has $d/2$ primitive roots (all the odd powers are generators). Moreover, if $g=x^q$ is not a primitive root, then it’s an even power, so $g^{d/2} = 1$.

That implies a simple Las Vegas algorithm: Randomly choose a nonzero $x \in F$, set $g=x^q$, and if $g^{d/2} \neq 1$ then output $g$, otherwise repeat. Since the probability of success is $1/2$, the expected number of rounds is 2.

Computational cost of the FFT

Each time the degree is cut by half, the depth is $\log_2 d = D$. In each layer, there are $O(d)$ operations: at layer $i$ there are $2^i$ polynomials of degree $2^{d-i}$, each pair of polynomials requires $2^{d-i+2}$ operations to compute the degree $2^{d-i+1}$ polynomial. For a total of $2^{i-1} \times 2^{d-i+2}= 2d$ operations.

So overall $2 d \log_2 d$ field operations.

Interpolation: inverse FFT

Given $d$ evaluations $P(\omega^1),\dots,P(\omega^d)$ can we interpolate and compute the coefficients $\vec{a}$ of $P(X)$ in $O(d \log d)$ operations? Yes, using the same two ingredients!

Let’s look again at

\[P(X)= P_e(X^2) + XP_o(X^2)\]If we had $d/2$ evaluations, $P_e(\omega^2),P_e(\omega^4),\dots,P_e(\omega^d)$ and $d/2$ evaluations, $P_o(\omega^2),P_o(\omega^4),\dots,P_o(\omega^d)$ then we could recursively obtain the coefficients $\vec{b},\vec{c}$ of $P_e(X)$ and $P_o(X)$ respectively.

Now via $(\ref{\star})$ get that $a_{2i}=b_i$ and $a_{2i-1}=c_i$ directly.

So the only challenge is to compute $\vec{e}=P_e(\omega^2),P_e(\omega^4),\dots,P_e(\omega^d)$ and $\vec{o}=P_o(\omega^2),P_o(\omega^4),\dots,P_o(\omega^d)$ from $\vec{y}=P(\omega^1),\dots,P(\omega^d)$.

As expected we will use the properties of roots of unity.

For any $1 \le j \le d/2$ to compute $o_j$ and $e_j$ we start with two equations by evaluating $(\ref{\star})$ at $\omega^j$ and $\omega^{d/2+j}$:

\[P(\omega^j) = P_e(\omega^{2j}) + \omega^j P_o(\omega^{2j})\]and

\[P(\omega^{d/2+j}) = P_e(\omega^{2j}) - \omega^j P_o(\omega^{2j})\]Where in the second equation we use $\omega^{d+x}=\omega^x$ and $\omega^{d/2+x}= -\omega^x$. The latter follows from $\omega^{d/2}=-1$ which can be derived from $(\omega^{d/2})^2 -1 =0 = (\omega^{d/2}-1)(\omega^{d/2}+1)$. Now note that $\omega^{d/2} -1 \neq 0$ because $\omega$ is a primitive $d$-th root of unity, so it must be that $\omega^{d/2} + 1 = 0$.

Using the notation $y,e,o$ we get:

\[y_j = e_j + \omega^j o_j\]and

\[y_{d/2+j} = e_j - \omega^j o_j\]Adding $(9)$ to $(10)$ and then dividing by 2 we get:

\[e_j=(y_j+y_{d/2+j})/2\]While subtracting $(10)$ from $(9)$ and then dividing by $2\omega^j$ we get:

\[o_j=(y_j-y_{d/2+j})/2\omega^j\]So we can compute $e_j,o_j$ using a constant number of field operations on $y_j,y_{d/2+j}, \omega^j$, hence compute all of them in $O(d)$ operations.

Again we have $\log_2 d$ layers of recursion and each layer requires $O(d)$ operations for a total of $O(d \log d)$ operations.

Inverse FFT via Inversion

The FFT is a linear transformation of the Vandermonde matrix where $V_{i,j}=\omega^{ij}$. The inverse matrix is $U_{i,j}= \omega^{-ij}/d$. This can be seen as the $i,j$ value of the product $VU$ is $(VU)_{i,j} = \frac{1}{d} \sum_k \omega^{k(i-j)}$ which equals 1 for $i=j$ and 0 otherwise (because $(\omega -1 )(1+\omega+\dots+\omega^{d-1}) = \omega^d -1 = 0$). Hence, running the regular FFT with $\omega^{-1}$ and dividing by $d$ is the same as multiplying by the inverse $U$. This obtains inverse FFT as well.

Do we need fields of characteristic $q 2^D+1$?

The requirement to have a field of characteristic $q 2^D+1$ is limiting. What if we are using a field that does not have a large power of two as a root of unity, but we still want to work with large, degree at most $d-1$ polynomials? Recent work of Ben-Sasson, Carmon, Kopparty, and Levit shows how to do FFT for any field in $O(d \log d)$ operations!

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Gilad Stern, Valeria Nikolaenko, and Dan Boneh for insightful discussions and comments.

Your comments and thoughts on x.