Multi-exponentiations and multi-scalar multiplications (MSMs) are computations that are widely used in cryptographic proof systems, mostly in proof generation and proof verification. This note outlines an efficient method for verifying the results of these computations, which opens the door to outsourcing them. In particular, by employing this technique it is possible to have the prover in a cryptographic proof system perform a significant portion of the computation that is usually run by the verifier.

The core idea involves breaking down the computation into smaller, batch-verifiable sub-computations. The efficiency gain stems from significantly reducing the length of the exponents used in the verification process. The theoretical performance gain is by a factor of roughly $m/(\lambda+\log m)$, where $m$ is the order of the group and $\lambda$ is a statistical security parameter. Experimental results support the theoretical analysis, with speedups ranging from 3.5X to 5X for representative parameter settings.

Introduction

A multi-exponentiation is a computation of the form $\prod_{i=1}^{n} v_i^{d_i}$, where the $v_i$ values are group elements and the exponents $d_i$ are scalars. Let us denote the bit length of the exponents by $m$. In most common use cases, the exponents are taken modulo the group order. We can set $m=256$ as a representative value for $m$. The number $n$ of group elements $v_i$ is much larger, in the order of thousands or even millions. A multi-scalar multiplication (MSM) is the equivalent to a multi-exponentiation in cyclic additive groups, typically elliptic curves. It involves calculating the sum of multiple scalar multiplications, and can be expressed as computing $\sum_{i=1}^{n} d_i P_i$, where the $P_i$ values are points on the curve and the $d_i$ values are scalars. In the rest of this note, we will interleave the usage of the terms multi-exponentiation and multi-scalar multiplication (MSM), as our optimization can be applied to both tasks in an almost identical way. In the description of the schemes, we use a multiplicative notation that corresponds to multi-exponentiations.

The runtime of computing an MSM

Computing a multi-exponentiation or an MSM is resource-intensive in terms of computation. There are three common approaches for improving the run time of these operations.

- The first approach is using Pippinger’s algorithm [P80, B02], which improves the overhead on an $n$-wide multi-exponentiation to be roughly the same as computing $O(n/ \log n)$ independent exponentiations. This is an improvement by a factor of about $\log n$ compared to the baseline of computing each exponentiation independently.

- The second approach uses some precomputation, which is beneficial if the same bases $v_i$ are used in multiple multi-exponentiations.

- The third approach speeds MSM computation using hardware accelerators such are GPUs or FPGAs. (See, for example, the following review.)

Cryptographic use-cases of MSMs

MSMs are used in various cryptographic tasks, particularly in the creation of zero-knowledge proofs and their verification. We are motivated by use-cases in which the runtime of proof verification is dominated by MSM computation. For example, MSMs dominate the runtime of the verifier in Bullet proofs (see page 29 in the Bullet proofs paper), and in Halo2 proofs. Both of these proof systems are widely used in numerous applications.

Naively, the overhead of the verifier can be reduced by asking the prover to compute the multi-exponentiation. This is, of course, insecure, as the prover could cheat by sending an incorrect result. The goal is to enable the verifier to check the correctness of the result much more efficiently than computing it from scratch. This benefit becomes particularly useful when a single multi-exponentiation or MSM needs to be verified by multiple verifiers.

Motivation

Checking instead of computing

Our goal is to verify the computation of a multi-exponentiation in a multiplicative group $G$. As we wrote earlier, we focus on the scenario where a multi-exponentiation or a multi-scalar multiplication (MSM) is employed during the verification of a cryptographic proof, and represents a significant computational bottleneck for the verifier. (It it important to emphasize that “verification” is performed twice: First, in a cryptographic proof system there is a verifier that needs to verify a proof. The work of this verifier is dominated by computing an MSM. The verifier therefore outsources the computation of the MSM and needs to verify the result it receives. It is natural to outsource the computation of the MSM to the prover of the cryptographic proof. The proof then contains the orignal proof, the result of the MSM, and a proof that the MSM was computed correctly. The verifier verifies the result of the MSM, and then uses it to verify the original proof.)

Observe that the cost of computing an MSM by a verifier might be significantly higher than the cost of the prover computing this MSM. This can be caused by several factors:

- In many cases, the verifier is a client machine whereas the prover is a dedicated server. As a result, the verifier typically has less computational resources than the prover. In particular, the verifier might not have access to hardware acceleration in the form of GPUs or FPGAs that are commonly used to accelerate MSM computation.

- Each proof might need to be verified by many different verifiers. As an example application, consider a distributed key generation (DKG) protocol with $N$ participants, that jointly generate a secret-sharing of a random key. In this protocol, each participant deals a random key, and the final key is the sum of all $N$ keys dealt by the participants. Each participant acts once as a dealer, and acts $N-1$ times as a receiver. Suppose that the verification of the message received from the dealer requires computing a multi-exponentiation. In a basic implementation, each participant has to compute $N-1$ multi-exponentiations as a receiver (verifier). Reducing the cost of verifying a multi-exponentiation can lead to a significant performance improvement. Moreover, for each dealer, the same multi-exponentiation must be computed by all $N-1$ receivers that verify the message sent by the dealer. As a result, offloading (most of) the cost of this single multi-exponentiation to the dealer can save (up to) a factor of $N$ in the total computation.

A birds-eye view

The basic setting of an interactive proof system includes a prover, a verifier, an input $x$ and a language $L$. The verifier receives from the prover a statement for the claim that $x\in L$. (We ingore here any zero-knowledge requirements from the proof.)

The verifier runs a verification procedure for checking the correctness of the proof. In most interesting cases, the cost of verifying the proof that $x\in L$ is much smaller than the verifier computing by itself whether $x\in L$.

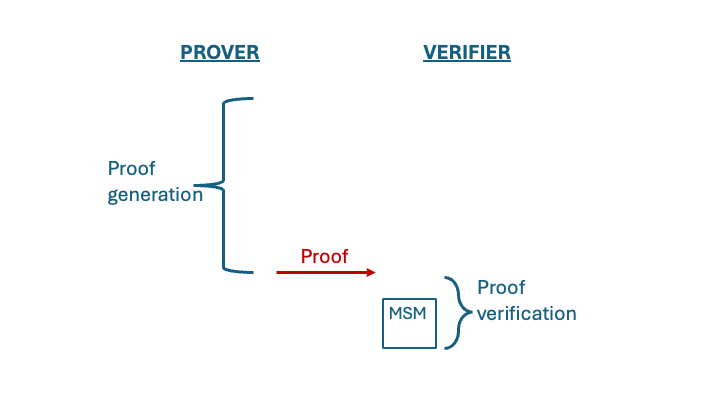

Suppose that the verification procedure includes computing a multi-exponentiation or an MSM. This is depicted in the next image, where the verification process is shorter than the proof and is dominated by computing the MSM.

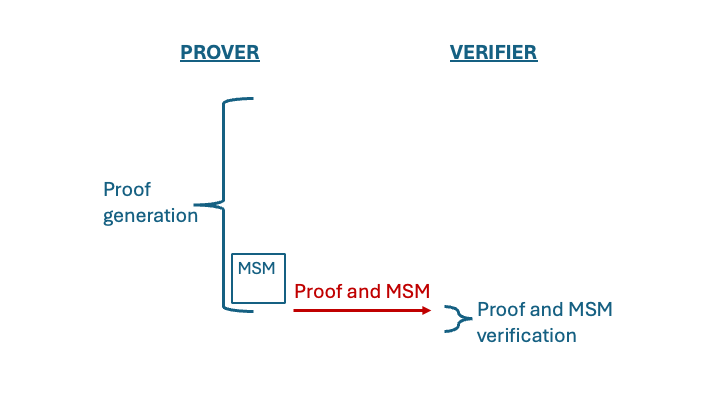

Our goal is to have the prover compute the MSM for the client and prove that this MSM was computed correctly. In other words, we offload part of the verification cost to the prover. The work of the prover is now larger, since it includes the original proof as well as part of the verification work (the MSM) and a proof that this MSM was computed correctly. On the other hand, the verification procedure does not need to compute the MSM and instead it only checks its correctness. This is depicted in the following image.

In other words, we replace the original proof procedure with a longer proof procedure, and gain an improvement in the work of the verifier. (Since checking the MSM in this method requires computing another MSM, albeit with much shorter exponents, it is tempting to continue this process recursively. However, we do not know how to do that.)

In other words, we replace the original proof procedure with a longer proof procedure, and gain an improvement in the work of the verifier. (Since checking the MSM in this method requires computing another MSM, albeit with much shorter exponents, it is tempting to continue this process recursively. However, we do not know how to do that.)

The problem

The setting includes two types of parties. The first is an untrusted prover, which is responsible for computing the multi-exponentiation. The second is the verifier, whose role is to verify the correctness of the multi-exponentiation. The goal is to enable the verifier to verify the correctness of the multi-exponentiation much more efficiently than computing it directly.

The solution

Preliminaries

The basic concept is to break down the computation of a multi-exponentiation into simpler sub-computations. These sub-computations can be verified as a batch much more efficiently than performing the original multi-exponentiation. The prover is therefore asked to compute these sub-computations, which are then batch-checked by the verifier. (This approach is motivated by results from the theory of computation on program checking, pioneered by [Blum and Kannan] and adapted to a cryptographic setting by [Frankel, Gemmell and Yung], and results on verification of delegated computation, e.g. [GGH+].)

The multi-exponentiation is an $n$-wise multi-exponentiation with $m$-bit long exponents. In comparison, verification will be done by computing an $n$-wise multi-exponentiation with exponents that are $(\lambda+\log m)$-bit long, where $\lambda$ is a statistical security parameter. Since the run time is linear in the length of the exponent, the theoretical improvement of the run time is by a factor of $m\over \lambda+\log m$. A representative value for $\lambda$ is $\lambda=64$, although some applications might set the statistical security parameter to be $\lambda=40$ or even smaller. For $m=256$ and $\lambda=64$, verification uses exponents which are $72$ bits long. Verification should therefore be about $256/72=3.55$ times faster than the baseline of computing the original multi-exponentiation.

Prerequisites:

- It is crucial that the group $G$ in which the multi-exponentiation is computed has an order that does not have small factors. This is the case, for example, with the popular Ristretto255 and BLS12-381 groups, which have a prime order. (The property that is ensured by this, and must be satisfied in order for the protocol to be secure, is that each value different than $1$ has an order of at least $2^{\lambda}$.)

- The efficiency gain that we anticipate is based on the assumption that the multi-exponentiation uses exponents that are uniformly distributed, or at least that the expected value of the exponent is close to the order of the group. (If that is not the case, then the expected gain in performance will be smaller.)

Solution

Denote the binary representation of the exponent $d_i$ as $d_i = d_{i,0} + 2d_{i,1} + \ldots + 2^{m-1}d_{i,m-1}$. The multi-exponentiation can be written as:

\[\prod_{i=1}^{n} v_i^{d_i} = \prod_{i=1}^{n} v_i^{\sum_{j=0}^{m-1} 2^j d_{i,j}} = \prod_{i=1}^{n} \prod_{j=0}^{m-1} v_i^{2^j d_{i,j}} = \prod_{j=0}^{m-1} \prod_{i=1}^{n} v_i^{2^j d_{i,j}} = \prod_{j=0}^{m-1} (\prod_{i=1}^{n} v_i^{d_{i,j}})^{2^j}\]Let us define

\[w_j = \prod_{i=1}^{n} v_i^{d_{i,j}}\]That is, $w_j$ is the multiplication of the values $v_i$ for which the $j$th bit of the corresponding exponent is 1. The multi-exponentiation can therefore be written as:

\[\prod_{j=0}^{m-1} w_j^{2^j}\]The prover is asked to compute the intermediate values $w_0,\ldots,w_{m-1}$ and send them to the verifier. The verifier can then compute the multi-exponentiation by computing $\prod_{j=0}^{m-1} w_j^{2^j}$ (this computation can be done using $m$ multiplications and $m$ squarings, as we show below). The primary challenge is to facilitate the verifier’s efficient verification of the accuracy of the $w_j$ values.

Verification – checking the correctness of the $w_i$ values

For $j=1,\ldots,m-1$, the verifier must check that $w_j = \prod_{i=1}^{n} v_i^{d_{i,j}}$, where the $v_i$ bases and the $d_{i,j}$ bits are public, and the same $v_i$ bases are used for computing all $w_j$ values.

The verifier chooses $m$ random coefficients $r_0,\ldots,r_{m-1} \in { 0,1}^{m\times \lambda}$, and runs two computations. In the first computation that it makes, it raises each $w_j$ to the power of $r_j$, and multiplies the results. In the second computation that it makes, it raises each $v_i$ to the power of $\sum_{j=0}^{m-1} r_j d_{i,j}$ (namely, the sum of the $r_j$ coefficients for which $d_{i,j}=1$), and multiplies the results. The verifier compares the two resulting values. In other words, the verifier computes the following two values, compares them and aborts if they are different:

- $w’ = \prod_{j=0}^{m-1} w_j^{r_j}$. This is done using an $m$-wise multi-exponentiation with $\lambda$-bit long exponents. (Recall that $m\ll n$ and therefore this computation is much faster than an $n$-wise multi-exponentiation.)

- $w’’ = \prod_{i=1}^{n} v_i^{\sum_{j=0}^{m-1} r_j d_{i,j}}$. This is done using an $n$-wise multi-exponentiation with $(\lambda+\log m)$-bit long exponents. This is the main overhead of the verification.

Claim: If not all $w_i$ values are correct, then the two values $w’$ and $w’’$ are different with probability $\geq 1- 2^{\lambda}$.

Proof: Note that

\[w'' = \prod_{i=1}^{n} v_i^{\sum_{j=0}^{m-1} r_j d_{i,j}} = \prod_{i=1}^{n} \prod_{j=0}^{m-1} v_i^{ r_j d_{i,j}} = \prod_{j=0}^{m-1} \prod_{i=1}^{n} v_i^{ r_j d_{i,j}} = \prod_{j=0}^{m-1} (\prod_{i=1}^{n} v_i^{d_{i,j}})^{r_j}\]The value $w’’$ is compared with $w’ = \prod_{j=0}^{m-1} w_j^{r_j}$. Suppose that there is a $j$ index such that $w_j$ is incorrect. For example, $j=0$ and $w_0 \neq \prod_{i=1}^{n} v_i^{d_{i,0}}$. The test done by the verifier is equivalent to checking whether

\[1\stackrel{?}{=} {w'\over w''} = \prod_{j=0}^{m-1} \left( { w_j \over \prod_{i=1}^{n} v_i^{d_{i,j}}}\right)^{r_j} = \left( { w_0 \over \prod_{i=1}^{n} v_i^{d_{i,0}}}\right)^{r_0} \cdot \prod_{j=1}^{m-1} \left( { w_j \over \prod_{i=1}^{n} v_i^{d_{i,j}}}\right)^{r_j}\]Verification is only successful if

\[\left( { w_0 \over \prod_{i=1}^{n} v_i^{d_{i,0}}}\right)^{r_0} = \left( \prod_{j=1}^{m-1} \left( { w_j \over \prod_{i=1}^{n} v_i^{d_{i,j}}}\right)^{r_j}\right)^{-1}\]Since ${ w_0 / \prod_{i=1}^{n} v_i^{d_{i,0}}} \neq 1$ and the order of the group is prime and greater than $2^{\lambda}$, all values $({ w_0 / \prod_{i=1}^{n} v_i^{d_{i,0}}})^{r_0}$ are different. The choice of $r_0$ is independent of the right-hand side, and, therefore, the probability that the above equation holds is at most $2^{-\lambda}$.

On setting the security parameter $\lambda$

The verification is done by a verifier that chooses its own randomness. This choice cannot be affected by the prover. (If multiple verifiers check the same multi-exponentiation, each one of them chooses its random exponents $r_j$ independently of the other verifiers.) The property that is guaranteed by the verification is that, independently of the prover’s choice of $w_j$ values, the verifier can detect incorrect values with probability $1-2^{-\lambda}$. This is a statistical security guarantee. Commonly used values for the statistical security parameter are $\lambda=40$ or $\lambda=64$. Even smaller values of $\lambda$ might be used in specific applications, as is further discussed below.

A note about the inadequacy of using the Fiat-Shamir paradigm

When the Fiat-Shamir proof paradigm is used, a prover can mount a brute-force search for a challenge, namely a set of $r_i$ exponents that makes the proof pass. Therefore, the analysis given here does not hold when the exponents are chosen by the prover using the Fiat-Shamir paradigm. (In that case, the security parameter $\lambda$ should be set to be at least $\lambda=128$.) The correct procedure involves the verifier selecting the random exponents $r_0,\ldots,r_{m-1}$ and executing the computations using these values.

More details about the overhead

The baseline with which we compare performance is where the verifier computes the multi-exponentiation $\prod_{i=1}^{n} v_i^{d_i}$ directly.

The overhead of our optimized approach is composed of the following components:

- The prover needs to send $m$ group elements to the verifier. (This is a communication of $m$ extra group elements compared to the baseline.)

- The verifier needs to compute

This can be done using $m$ multiplications and $m$ squarings, which is much faster than computing an $n$-wise multi-exponentiation directly.

- The verifier needs to verify that each $w_j$ value is correct. As we described, this property can be batch-verified for $w_j$ values using a single $n$-wide multi-exponentiation, where the exponents are $\lambda+\log(m)$ bits long.

Since the overhead of the multi-exponentiation is linear in the length of the exponents, performance is roughtly improved by a factor of $m/(\lambda+\log m)$.

Methods for improving the runtime of multi-exponentiations / MSMs

Computing a multi-exponentiation can be optimized using Pippinger’s algorithm [P80, B02]. The overhead is roughly the same as computing $O(n/ \log n)$ independent exponentiations with exponents of the same length as the original exponents. The overhead of both the straightforward computation of a multi-exponentiation and that of Pippinger’s algorithm, depends linearly on the length of the exponents. Our optimization reduces the length of the exponents and can therefore be applied with an equal effect to Pippinger’s optimization. (This is demonstrated by the experiments described below, which measure the runtime of a multi-exponentiation library that uses Pippinger’s optimization.)

There are well-known methods for improving the runtime of multi-exponenitations, and in particular MSMs, using precomputation. These methods require knowing in advance the values of the base points $v_i$. If that is the case then these precomputation methods can be applied to our optimized computation as well

Further efficiency improvements

Changing the range of the exponents: Choosing the exponents $r_j$ from the range $[-2^{\lambda-1},2^{\lambda-1}]$ makes the sums $\sum_{j=0}^{m-1} r_j d_{i,j}$ concentrated w.h.p. in the range $[-O(2^{\lambda-1}\sqrt{m}), O(2^{\lambda-1}\sqrt{m})]$. This means that computing the value $w’’$, which is the main overhead of the verification, now involves computing a multi-exponentiation with exponents of length about $\lambda+ 0.5\log m$ bits, instead of $\lambda+ \log m$ bits. (For $\lambda = 64, m=256$ the reduction is by a factor of $72/68 \approx 1.06$, which is quite marginal.)

We note that in order to use this approach it is not essential that all sums are in the range $[-O(2^{\lambda-1}\sqrt{m}),O(2^{\lambda-1}\sqrt{m})]$. Rather, it is sufficient to observe that w.h.p. the sums do not deviate by much from this range. The additional cost of computing sums that are outside of the range is small.

Special cases where smaller exponents might be sufficient: In some applications it might be sufficient to provide only covert security. Namely, only ensure that malicious behavior is identified with some moderately high probability, say $99.9999\%$. This is true for applications where malicious behavior can be punished, say by slashing the revenues of the malicious party. In such cases the statistical security parameter $\lambda$ might be reduced. For example, the system can use $\lambda=20$ in order to ensure that cheating is identified with probability greater than $1-10^{-6}$.

In some consensus applications it might be possible to reduce $\lambda$ based on another argument that is more interleaved with the consensus protocol. Suppose, for example, that the number of potentially corrupt parties is $t<n/3$, and that the transcript sent by a participant must be signed by $2t+1$ participants. Then, even if each verifier identifies cheating with some moderate probability $p$, say $p=1/4$, the probability that $t+1$ out of the $2t+1$ honest verifiers agree to sign the transcript is exponentially small in $t$.

A comment about the run time of the dealer

The dealer must compute $m=256$ values $w_j = \prod_{i=1}^{n} v_i^{d_{i,j}}$. Assuming that the $d_{i,j}$ values are random bits, these $w_j$ values are the results of multiplying random subsets of the same $n$ group elements. A straightforward implementation of this computation requires computing about ${m n\over 2}$ multiplications.

The overhead of computing these subset multiplications can be reduced by observing that they have large intersections. Consider for example the computation of $w_0$ and $w_1$. Define the following subsets of indexes

\[\begin{eqnarray*} S_{1,1} & = & \{ i\in [n] \mid d_{i,0} = 1 \; \mathrm{and} \; d_{i,1} = 1\} \\ S_{0,1} & = & \{ i\in [n] \mid d_{i,0} = 0 \; \mathrm{and} \; d_{i,1} = 1\} \\ S_{1,0} & = & \{ i\in [n] \mid d_{i,0} = 1 \; \mathrm{and} \; d_{i,1} = 0\} \end{eqnarray*}\]It holds that $|S_{1,1}| \approx |S_{0,1}| \approx |S_{1,0}| \approx n/4$. Let $P_{1,1} = \prod_{i\in S_{1,1}} v_i$, $P_{0,1} = \prod_{i\in S_{0,1}} v_i$, and $P_{1,0} = \prod_{i\in S_{1,0}} v_i$. Then $w_0 = P_{1,1}\cdot P_{1,0}$ and $w_1 = P_{1,1}\cdot P_{0,1}$. Therefore, after computing $P_{1,1},P_{0,1},P_{1,0}$ the dealer can compute each of $w_0$ and $w_1$ using a single multiplication. The entire computation requires $|S_{1,1}| + |S_{0,1}| + |S_{1,0}| +2 \approx 0.75n$ multiplications, and thus computing each $w_i$ value takes about $0.375n$ multiplications, compared to about $n/2$ multiplications in the naive computation.

In the general case, considering the computation of $s$ random subset multiplications, $w_0,\ldots,w_{s-1}$, a similar approach for the computation requires about $(1-2^{-s}) n$ $+ s\cdot (2^{s-1}-1)$ multiplications in total, or $(1-2^{-s}) n/s$ + $(2^{s-1}-1)$ multiplications per value. This should be compared with the naive computation that requires about ${sn\over 2}$ multiplications in total, or $n/2$ multiplications per value. Due to the $2^{s-1}$ term, the improvement is only significant for $s\ll \log n$.

Experiments

We ran experiments using a multi-exponentiation library written by Zhoujun Ma, which implements Pippinger’s multi-exponentiation algorithm. The library is written in Rust and can be found here.

The first experiment was run to verify that the runtime of computing multi-exponentiations in this library is linear in the length of the exponent. The following table shows the results of benchmarks for computing multi-exponentiations over BLS12-381, with different exponent lengths of 16, 32, 64, 128 and 256 bits. The order of the group is about $2^{255}$, corresponding to $m \approx 255$. The results were computed for multi-exponentiation widths ($n$) of 1000, 2000, 4000 and 8000. The run time is measured in milliseconds and is the median of 100 runs. All measurements were conducted on a MacBook Pro M1.

| n / exp length | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 256 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1000 | 1.92 | 3.56 | 6.74 | 13.32 | 25.95 |

| 2000 | 3.06 | 6.19 | 12.36 | 24.62 | 48.28 |

| 4000 | 5.76 | 12.11 | 22.48 | 43.15 | 83.53 |

| 8000 | 10.93 | 22.47 | 41.80 | 82.57 | 162.81 |

To further demonstrate that the runtime is linear in the exponent length, the following table uses the results of the first experiment presents the ratio between the actual runtime and the theoretical runtime for each entry. The latter value is assuming a truly linear runtime and is computed by dividing the exponent length by 256 and multiplying the result by the run time for 256 bits. (For instance, the first entry in the table is $1.92$ divided by ${16\over 256}\cdot 25.95$.) All values in the table are close to 1, which is the theoretical optimum.

| N / exp length | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 256 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1000 | 1.184 | 1.097 | 1.039 | 1.027 | 1.000 |

| 2000 | 1.014 | 1.026 | 1.024 | 1.020 | 1.000 |

| 4000 | 1.103 | 1.160 | 1.076 | 1.033 | 1.000 |

| 8000 | 1.074 | 1.104 | 1.027 | 1.014 | 1.000 |

| Average | 1.094 | 1.097 | 1.042 | 1.023 | 1.000 |

The second experiment checks the performance gain of the verification process for both $\lambda =40$ and $\lambda=64$. The main overhead during the verification phase in the new construction is computing $w’’ = \prod_{i=1}^{n} v_i^{\sum_{j=0}^{m-1} r_j d_{i,j}}$. The exponent in this computation is computed by adding $m=255$ values that are each $\lambda=40$ or $\lambda=64$ bits long, and is therefore of length $\lambda+\log m$ bits. The comparison thus compares the baseline, which is the runtime of an $n$-wide multi-exponentiation with exponents of length $m=255$, to a multi-exponentiation with exponents of length $\lambda+\log m = \lambda+8$. The results are depicted in the next table. The run time is again in milliseconds and is the median of 64 runs. The table shows the runtime for exponents of lengths 48, 72, and 255 bits, respectively, corresponding to $\lambda=40$, $\lambda=64$ and the baseline. The width of the multi-exponentiations, $n$, ranges from 1,000 to 1,024,000. The table also shows the gain factor by which the runtime is improved compared to the baseline. The last row shows the theoretical gain, e.g.. ${255\over 48}=5.31$ for $\lambda =40$. The table demonstrates that the actual gains are very close to the theoretical gain.

| n | $\lambda=40$, exp len = 48, runtime | $\lambda=40$, exp len = 48, gain | $\lambda=64$, exp len = 72, runtime | $\lambda=64$, exp len = 72, gain | exp len = 255, runtime |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,000 | 4.72 | 5.36 | 7.3 | 3.46 | 25.28 |

| 4,000 | 15.9 | 5.00 | 22.4 | 3.55 | 79.49 |

| 16,000 | 51.66 | 5.53 | 81.38 | 3.51 | 285.85 |

| 64,000 | 173.43 | 5.43 | 259.03 | 3.64 | 942.09 |

| 256,000 | 676.1 | 4.79 | 989.05 | 3.28 | 3241.4 |

| 1,024,000 | 2321.2 | 5.25 | 3702.4 | 3.29 | 12192 |

| Ideal gain | 5.31 | 3.54 |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ittai Abraham, Dan Boneh, Zhoujun Ma, Omer Shlomovits and Alin Tomescu for their help and feedback.

Please leave comments on X.