Accumulator schemes are an alternative to Merkle Hash Trees (MHTs) for committing to sets of elements. Their main advantages are:

- Constant-sized membership and non-membership proofs, an improvement over logarithmic-sized proofs in MHTs,

- Algebraic structure that enables more efficient proofs about committed elements1 (e.g., ZeroCoin2 uses RSA accumulators for anonymity),

- Constant-sized proofs for set relations such as subset, disjointness and difference (e.g., append-only authenticated dictionaries3 can be built using subset and disjointness proofs).

Their main disadvantages are:

- More computationally expensive due to elliptic curve group operations or hidden-order group operations (e.g., in $\mathbb{Z}_N^*$),

- Setting up an accumulator scheme typically requires a trusted setup phase, which complicates deployment,

- Some accumulator schemes are limited in the size of the sets they can commit to. (The limit is fixed during the trusted setup phase.)

In this post, we’ll talk about the ins and outs of bilinear accumulators4. (We hope to address RSA accumulators5 in a future post.) A bilinear accumulators can be regarded as a type of Kate-Zaverucha-Goldberg (KZG) polynomial commitment6. (Although it is not necessary for this post, you will find a brief summary of KZG here.)

Note: We use the term commitment here lightly. Specifically, we care more about the binding property rather than the hiding property. Nonetheless, some accumulators have hiding properties.

The setting

Just like with MHTs, we’ll consider accumulators in the setting of a prover and one or more verifiers. The prover will be the party committing to the set and computing proofs (e.g., membership, non-membership, disjointness). The verifiers will be the parties that verify proofs.

Example: Let’s consider Bitcoin. The prover is the Bitcoin miner that commits to the set of transactions (TXNs) and computes membership proofs for each TXN. The verifiers would be Bitcoin thin clients, which receive a TXN and verify its membership proof.

Typically, there will be some public parameters (PPs) needed for the prover to commit to a set and compute proofs. Furthermore, the verifier might need (a subset of) these parameters to verify proofs.

Example: For MHTs, the public parameters are simply the collision-resistant hash function (CRHF) used to compute the MHT. Both the prover and verifier have this CRHF (e.g., they know how to compute SHA256 hashes). In contrast, for accumulators, the PPs will typically consist of the description of an algebraic group (e.g., an elliptic curve or $\mathbb{Z}_N^*$) as well as some other group elements.

Bilinear accumulators

Bilinear accumulators make heavy use of polynomials, which we assume knowledge of below. They can also be regarded as a direct application of the Kate-Zaverucha-Goldberg (KZG) polynomial commitment scheme, which we do not assume knowledge of below.

Setting up an accumulator scheme

Recall that, to set up an MHT scheme, all that must be done is to agree on what CRHF will be used to hash the tree. With bilinear accumulators, things are a bit more complicated.

First, bilinear accumulators require a bilinear group $\mathbb{G}$7. Such groups have an efficiently-computable bilinear map $e : \mathbb{G}\times\mathbb{G}\rightarrow\mathbb{G}_T$, where $\mathbb{G}_T$ is another group called the target group. Let $g$ denote the generator of $\mathbb{G}$ and let $p$ denote the order of $\mathbb{G}$. The most important thing to know about bilinear maps is that they have very useful algebraic properties:

\begin{align*} e(g^a,g^b)=e(g^a,g)^b=e(g,g^b)^a=e(g,g)^{ab}, \forall a,b\in \mathbb{Z}_p \end{align*}

Second, bilinear accumulators can only be used to commit to sets of bounded size $\ell$. For this, the prover needs $\ell$-Strong Diffie-Hellman ($\ell$-SDH) public parameters:

\begin{align*} \left(g^{\tau^i}\right)_{i=0}^{\ell} &= (g, g^\tau, g^{\tau^2}, g^{\tau^3},\dots,g^{\tau^\ell}) \end{align*}

Here, $\tau$ is a trapdoor: a random number in $\mathbb{Z}_p$ that must not be made public or else the accumulator scheme will be completely insecure. (We’ll discuss what “security” means later.) Thus, generating PPs has to be done in a manner that never reveals $\tau$. This is called a trusted setup phase and can be implemented naively via a trusted third party (TTP).

Example: The TTP would take as input $\ell$, pick a random $\tau$, compute $\left(g^{\tau^i}\right)_{i=0}^\ell$ and promise to forget $\tau$.

Since TTPs should be avoided in practice, the TTP can be implemented in a “decentralized” manner via multiple parties8,9. This way, all parties must collude in order to learn $\tau$, which means a single honest party suffices to keep $\tau$ secret.

Warning: This requirement of a trusted setup phase is a disadvantage of bilinear accumulators, since it complicates the set up of the scheme. As we’ll see later, in some settings, RSA accumulators have the advantage of not needing a trusted setup.

Committing to sets

The prover can commit to or accumulate any set $T=\{e_1,e_2,\dots,e_n\}$ where $e_i \in \mathbb{Z}_p$ and $n < \ell$. First, the prover computes an accumulator polynomial $\alpha$ which has roots at all the $e_i$’s:

\begin{align}

\alpha(X) &= (X-e_1)(X-e_2)\cdots(X-e_n)\label{eq:acc-poly}\\

&= \prod_{j\in[n]} (X-e_j)

\end{align}

Here, “computing a polynomial” means computing its coefficients $(a_0, a_1, \dots, a_n)$ given its roots (i.e., the $e_i$’s) such that $\alpha(X)=\sum_{i=0}^n a_i X^i$. Also, note that the $a_i$’s are elements of $\mathbb{Z}_p$ and $\alpha$ has degree $n$.

Second, the digest or accumulator of $T$ is set to $a=g^{\alpha(\tau)}$, computed as:

\begin{align*}

a &= \prod_{i=0}^n \left(g^{\tau^i}\right)^{a_i}\\

&= \prod_{i=0}^n g^{a_i \tau^i}\\

&= g^{\sum_{i=0}^n {a_i \tau^i}}\\

&= g^{\alpha(\tau)}

\end{align*}

In other words, the prover simply computes $\alpha(\tau)$ “in the exponent”, using the $\ell$-SDH PPs and the fact that $\alpha(\tau) = \sum_{i=0}^n a_i \tau^i$.

And that’s it! The digest of the set is just the single group element $a\in \mathbb{G}$. Depending on the types of algebraic groups used, this could be as small as 32 bytes!

Computing the coefficients of the accumulator polynomial

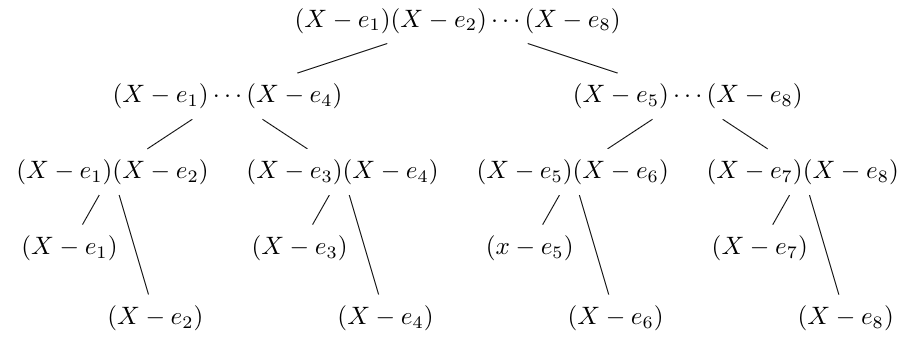

You might wonder: “How do I compute the coefficients $a_i$ of $\alpha$ given its roots $e_i$?” The key idea is to start with monomials $(X-e_i)$ as leaves of a binary tree and multiply up the tree to obtain $\alpha(X)$’s coefficients at the root.

Here’s an example for a set $T=\{e_1, e_2, \dots, e_8\}$:

Let’s see how long it takes to compute $\alpha$ in this manner. First, recall that two degree-$n$ polynomials can be multiplied fast in $O(n\log{n})$ time using the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) (see Chapter 30.1 in CLRS10). Second, let’s (recursively) define the time $t(n)$ to compute the tree on $n$ leaves as the sum of:

- The time $2\cdot t(n/2)$ to compute its two subtrees of $n/2$ leaves, and

- The $O(n\log{n})$ time to multiply the two degree-$(n/2)$ polynomials at the root of these two subtrees (via DFT).

More formally, $t(n)=2t(n/2)+O(n\log{n})$, which simplifies to $t(n)=O(n\log^2{n})$ time.

Concrete performance: The $O(n\log^2{n})$ time to compute $\alpha$ is the most costly step, asymptotically. However, in a concrete implementation, more time is spent computing $g^{\alpha(\tau)}$. To speed this up, a fast multi-exponentiation11 algorithm should be used.

Updating commitments

Unlike MHTs and RSA accumulators, bilinear accumulators cannot be efficiently updated. Specifically, given an old accumulator $a=g^{\alpha(\tau)}$, the prover cannot efficiently compute the new accumulator $a’=g^{\alpha’(\tau)}$, after a new element $e’$ has been added to the accumulator (i.e., $\alpha’(X) = \alpha(X) (X-e’)$).

Instead, the prover has to:

- Multiply $\alpha(X)$ by $(X-e’)$ in $O(n)$ time to obtain $\alpha’(X)$,

- Commit to $\alpha’(X)$ from scratch in $O(n)$ time.

Thus, if done naively, updates take $O(n)$ time, which is very expensive. (In an MHT, they take $O(\log{n})$ time and in RSA accumulators they take $O(1)$ time.)

So, is there any hope to speed up updating accumulators? Fortunately, classic static-to-dynamic transformations12 can be used to enable more efficient updates for bilinear accumulators, although at some costs. For example, we take this approach in our work when designing and implementing append-only authenticated dictionaries3. The details are outside the scope of this post.

Computing membership proofs

Now that we know how to accumulate sets, let’s talk about how to prove membership of elements w.r.t. the accumulator of a set. Looking back at Equation \ref{eq:acc-poly}, we notice that $e_i$ is in the accumulator if, and only if, $(X-e_i)$ divides $\alpha(X)$. Accumulator membership proofs leverage this observation!

Another way to look at this is that $e_i$ is in the accumulator if, and only if, $\alpha(e_i)=0$. But $\alpha(e_i)=0$ is equivalent to $(X-e_i)$ divides $\alpha(X)$!

To compute a membership proof, the prover first divides $\alpha$ by $(X-e_i)$ obtaining a quotient polynomial $q(X)$ of degree $n-1$:

\begin{align*} \alpha(X) = q(X)(X-e_i) \end{align*}

Some simple math shows the quotient $q(X)$ is just $\alpha(X)$ without a root at $e_i$:

\[q(X) = \prod_{j\in[n]\setminus\{i\}} (X-e_j)\]Second, the prover commits to $q(X)$ using the same algorithm we described for $\alpha(X)$. The proof is the commitment $g^{q(\tau)}$.

Note: Dividing $\alpha$ by $(x-e_i)$ takes $O(n)$ time and committing to the quotient $q$ also takes $O(n)$ time. (As before, the commitment step is more expensive in practice and should be implemented with a multiexp11.)

This is easier to see with an example, so let’s consider the set \(T=\{5,7,10\}\). The accumulator is $g^{(\tau-5)(\tau-7)(\tau-10)}$. The proof for element $5$ is just $g^{(\tau-7)(\tau-10)}$. This is just a commitment to the quotient:

\[q(X) = \frac{\alpha(X)}{(X-5)}=\frac{(X-5)(X-7)(X-10)}{(X-5)} = (X-7)(X-10)\]Similarly:

- The proof for element $7$ is just $g^{(\tau-5)(\tau-10)}$.

- The proof for element $10$ is just $g^{(\tau-5)(\tau-7)}$.

Verifying membership proofs

Let $a = g^{\alpha(\tau)}$ be the accumulator, $e_i$ be the element we’re verifying membership of and $\pi=g^{q(\tau)}$ be the proof. To verify $e_i$ is accumulated, we’ll use the bilinear map $e$ to check that: \begin{align*} e(a, g) \stackrel{?}{=} e(\pi, g^\tau / g^{e_i}) \end{align*}

Note that this is equivalent to checking that:

\begin{align*}

e(g^{\alpha(\tau)}, g) &\stackrel{?}{=} e(g^{q(\tau)}, g^{\tau -e_i}) \Leftrightarrow \\

e(g,g)^{\alpha(\tau)} &\stackrel{?}{=} e(g^{q(\tau)}, g^{\tau -e_i}) \\

e(g,g)^{\alpha(\tau)} &\stackrel{?}{=} e(g,g)^{q(\tau)(\tau -e_i)} \\

\alpha(\tau) &\stackrel{?}{=} q(\tau)(\tau -e_i) \\

\end{align*}

In other words, we are verifying that the $\alpha(X) = q(X)(X-e_i)$ equation holds only for $X=\tau$ rather than for all $X$. It turns out that, as long as nobody knows $\tau$, this is sufficient for security under the $\ell$-SDH assumption, which was originally introduced by Boneh et al13.

Important: To verify proofs, the verifier needs a small subset of the public parameters: just $g$ and $g^\tau$.

Updating membership proofs

Suppose we have an accumulator $a$ for \(\{e_1, \dots, e_n\}\) and we also have membership proofs $\pi_i$ for each $e_i$. If a new element $e_{n+1}$ is added to the accumulator, it seems like we would have to recompute all proofs $\pi_i$ for each $e_i$. This would take $O(n^2)$ time, which is impractical for large $n$.

Fortunately, there is an efficient way to update all membership proofs after a single element $e_{n+1}$ was added to the accumulator4. The idea is to update each proof $\pi_i$ to $\pi’_i$ as:

\[\pi'_i = a \cdot \pi_i^{e_{n+1}-e_i}\]To see why this works, note that:

\begin{align*}

\pi’_i &= a \cdot \pi_i^{e_{n+1}-e_i}\\

&= g^{\prod_{j\in[n]} (\tau - e_j)} \cdot \left(g^{\prod_{j\in[n]\setminus\{i\}} (\tau-e_j)}\right)^{-(e_{n+1}+e_i)}\\

&= \left(g^{\prod_{j\in[n]\setminus\{i\}} (\tau - e_j)}\right)^{(\tau - e_i)} \cdot \left(g^{\prod_{j\in[n]\setminus\{i\}} (\tau-e_j)}\right)^{(-e_{n+1}+e_i)}\\

&= \left(g^{\prod_{j\in[n]\setminus\{i\}} (\tau - e_j)}\right)^{(\tau - e_i) + (-e_{n+1}+e_i)}\\

&= \left(g^{\prod_{j\in[n]\setminus\{i\}} (\tau - e_j)}\right)^{(\tau - e_{n+1})}\\

&= g^{\prod_{j\in[n+1]\setminus\{i\}} (\tau - e_j)}

\end{align*}

There is also a similar technique for updating proofs after a single element deletion (see Section 4, pg. 10, in the original paper on bilinear accumulators4). Lastly, Papamanthou also gives a proof update techniques when a single element is modified in the accumulator (see Lemma 3.16 in his thesis14).

Still, compared to MHTs, which can update all proofs in $O(\log{n})$ time, updating all proofs in $O(n)$ time remains slow for many bilinear accumulator applications. This seems to the cost paid to get constant-sized membership proofs.

Computing non-membership proofs

It is also possible to create a non-membership proof that an element $\hat{e}\notin T$ is not in the accumulator. We just have to (somehow) show that $\alpha(\hat{e})\ne 0$.

For this, we’ll leverage the polynomial remainder theorem (PRT), which says that:

\begin{align*} \forall\ \text{polynomials}\ \phi,\forall k, \exists\ \text{polynomial}\ q,\ \text{s.t.}\ \phi(X) = q(X)(x - k) + \phi(k) \end{align*}

Now, suppose we have an element $\hat{e}$ that is not in the accumulator. This means $\alpha(\hat{e}) = y$ where $y \ne 0$. In other words, by applying the PRT, we get:

\[\alpha(\hat{e}) = y \Leftrightarrow \exists q, \alpha(X) = q(X)(x - \hat{e}) + y\]The non-membership proof will consist of (1) a commitment to $q$ (as before) and (2) the non-zero value $y=\alpha(\hat{e})$.

Let $\pi=g^{q(\tau)}$ denote the quotient commitment. The proof verification remains largely the same:

\begin{align*} e(a, g) \stackrel{?}{=} e(\pi, g^\tau / g^{\hat{e}})e(g,g)^y \end{align*}

Note that this is equivalent to checking that:

\begin{align*}

e(g^{\alpha(\tau)}, g) &\stackrel{?}{=} e(g^{q(\tau)}, g^{\tau -\hat{e}})e(g,g)^y \Leftrightarrow \\

e(g,g)^{\alpha(\tau)} &\stackrel{?}{=} e(g^{q(\tau)}, g^{\tau -\hat{e}})e(g,g)^y \\

e(g,g)^{\alpha(\tau)} &\stackrel{?}{=} e(g,g)^{q(\tau)(\tau -\hat{e})}e(g,g)^y \\

e(g,g)^{\alpha(\tau)} &\stackrel{?}{=} e(g,g)^{q(\tau)(\tau -\hat{e}) + y} \\

\alpha(\tau) &\stackrel{?}{=} q(\tau)(\tau - \hat{e}) + y

\end{align*}

As before, this only verifies that the $\alpha(X) = q(X)(X-\hat{e}) + y$ equation holds only for $X=\tau$ rather than for all $X$.

Note: The verification can be done more efficiently as $e(g^{\alpha(\tau)} / g^y, g) \stackrel{?}{=} e(g^{q(\tau)}, g^{\tau -\hat{e}})$.

Note: The $\alpha(X) = q(X)(X-e_i)$ equation we relied on for proving membership is just the PRT applied to $\alpha(e_i) = 0 $

Computing subset proofs (or batching membership proofs)

What if we want to prove $T_1 \subseteq T_2$ given their accumulators $a_1$ and $a_2$? One application of this is batching membership proofs: i.e., compute a single, constant-sized membership proof for multiple elements. This can be done by just setting $T_1$ to be the set of those elements.

Subset proofs are based on the observation that if $T_1 \subseteq T_2$, then $\alpha_1$ divides $\alpha_2$, where $\alpha_1$ and $\alpha_2$ are the accumulator polynomials of $T_1$ and $T_2$.

Example: If $T_1=\{1,3\}$ and $T_2=\{1,3,4,10\}$, then clearly $\alpha_1(X)=(X-1)(X-3)$ divides $\alpha_2(X)=(X-1)(X-3)(X-4)(X-10)$ and the quotient is $q(X)=(X-4)(X-10)$.

The subset proof is just a commitment to the quotient $q = \alpha_2 / \alpha_1$, which can be computed in $O(n\log{n})$ time using FFT-based division15, where $n$ is the max degree of the two polynomials.

To verify the proof $\pi=g^{q(\tau)}$ against the two accumulators $a_1 = g^{\alpha_1(\tau)}$ and $a_2 =g^{\alpha_2(\tau)}$, the bilinear map is used as expected:

\begin{align*}

e(a_1, \pi) &\stackrel{?}{=} e(a_2, g)\Leftrightarrow\\

e(g^{\alpha_1(\tau)}, g^{q(\tau)}) &\stackrel{?}{=} e(g^{\alpha_2(\tau)}, g)\Leftrightarrow\\

e(g,g)^{\alpha_1(\tau) q(\tau)} &\stackrel{?}{=} e(g,g)^{\alpha_2(\tau)}\Leftrightarrow\\

\alpha_1(\tau) q(\tau) &\stackrel{?}{=} \alpha_2(\tau)\Leftrightarrow\\

q(\tau) &\stackrel{?}{=} \alpha_2(\tau) / \alpha_1(\tau)

\end{align*}

Computing disjointness proofs

Disjointness proofs are based on the observation that if $T_1 \cap T_2 = \varnothing$, then $\exists$ polynomials $u(X),v(X)$ such that:

\[u(X)\alpha_1(X)+v(X)\alpha_2(X) = 1\]The $u,v$ polynomials can be computed using (fast versions of) the Extended Euclidean Algorithm (EEA)16 in $O(n\log^2{n})$ time, where $n$ is the max degree of the two polynomials.

The disjointness proof will be the $g^{u(\tau)}$ and $g^{v(\tau)}$ commitments to $u$ and $v$ respectively. By now, it should be easy to tell how to verify such a proof:

\begin{align*} e(a_1, g^{u(\tau)}) e(a_2, g^{v(\tau)}) &\stackrel{?}{=} e(g, g) \end{align*}

Conclusion

This post introduced bilinear accumulators, an alternative to MHTs that offers constant-sized (non)membership proofs.

Bilinear accumulators are more “expressive” than MHTs: they can prove subset and disjointness relations between sets. This is typically not possible to do efficiently with MHTs, which must be “organized” differently to allow for either efficient subset proofs or efficient disjointness proofs (but not both).

Unfortunately, the power of bilinear accumulators is paid for with:

- A more complicated (trusted) setup phase,

- More computational overhead,

- $O(\ell)$-sized public parameters for the prover to commit to sets of size $\le \ell$

In our next post, we’ll see how RSA accumulators can address (1) and (3), by further sacrificing on (2).

If you ever need to implement bilinear accumulators in C++, I found the following libraries useful:

- Victor Shoup’s libntl, for fast polynomial arithmetic like division and EEA

- Zcash’s libff, for fast elliptic curve groups with bilinear maps (e.g., BN254)

- Zcash’s libfqfft, for computing FFTs in the finite field $\mathbb{F}_p$ associated with libff’s elliptic curve groups of order $p$

You can also find my own C++ implementations, based on the libraries above, here:

- libaad, which implements bilinear accumulators and uses them to build more complicated append-only authenticated data structures3.

- libpolycrypto, which implements KZG polynomial commitments (which bilinear accumulators are based on)

Open problems

Many interesting problems remain open for bilinear accumulators:

- Efficiently updating accumulators after updates

- Efficiently updating non-membership proofs

- Efficiently updating subset and disjointness proofs

References

-

Zero-Knowledge Proofs for Set Membership, by Dario Fiore, in ZKProof Blog, 2020 ↩

-

Zerocoin: Anonymous Distributed E-Cash from Bitcoin, by Ian Miers and Christina Garman and Matthew Green and Aviel D. Rubin, in IEEE Security and Privacy ‘13, 2013 ↩

-

Transparency Logs via Append-Only Authenticated Dictionaries, by Tomescu, Alin and Bhupatiraju, Vivek and Papadopoulos, Dimitrios and Papamanthou, Charalampos and Triandopoulos, Nikos and Devadas, Srinivas, in ACM CCS ‘19, 2019, #shamelessplug ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Accumulators from Bilinear Pairings and Applications, by Nguyen, Lan, in CT-RSA ‘05, 2005 ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

One-Way Accumulators: A Decentralized Alternative to Digital Signatures, by Benaloh, Josh and de Mare, Michael, in EUROCRYPT ‘93, 1994 ↩

-

Constant-Size Commitments to Polynomials and Their Applications, by Kate, Aniket and Zaverucha, Gregory M. and Goldberg, Ian, in ASIACRYPT ‘10, 2010 ↩

-

A One Round Protocol for Tripartite Diffie–Hellman, by Joux, Antoine, in Algorithmic Number Theory, 2000 ↩

-

A Multi-party Protocol for Constructing the Public Parameters of the Pinocchio zk-SNARK, by Bowe, Sean and Gabizon, Ariel and Green, Matthew D., in Financial Cryptography and Data Security, 2019 ↩

-

Scalable Multi-party Computation for zk-SNARK Parameters in the Random Beacon Model, by Sean Bowe and Ariel Gabizon and Ian Miers, in Cryptology ePrint Archive, Report 2017/1050, 2017 ↩

-

Introduction to Algorithms, Third Edition, by Cormen, Thomas H. and Leiserson, Charles E. and Rivest, Ronald L. and Stein, Clifford, 2009 ↩

-

Pippenger’s Multiproduct and Multiexponentiation Algorithms (Extended Version), by Ryan Henry, 2010 ↩ ↩2

-

Static-to-dynamic tranformations, by Jeff Erickson, 2015, [URL] ↩

-

Short Signatures Without Random Oracles and the SDH Assumption in Bilinear Groups, by Boneh, Dan and Boyen, Xavier, in Journal of Cryptology, 2008 ↩

-

Cryptography for Efficiency: New Directions in Authenticated Data Structures, by Charalampos Papamanthou, 2011, [URL] ↩

-

Newton iteration, by von zur Gathen, Joachim and Gerhard, Jurgen, in Modern Computer Algebra, 2013 ↩

-

Fast Euclidean Algorithm, by von zur Gathen, Joachim and Gerhard, Jurgen, in Modern Computer Algebra, 2013 ↩