Guest post by Benjamin Chan and Elaine Shi

In this post, we describe an extraordinarily simple blockchain protocol called Streamlet. Consensus is a complex problem and has been studied since the 1980s. More recently, blockchain research has spawned many new works aiming for performance and ease-of-implementation. However, simple, understandable protocols remain elusive, and that’s where Streamlet comes in.

Streamlet in a nutshell:

-

The protocol proceeds in synchronized epochs.

-

Define a “notarized block” to be a block accompanied by votes (for that block) from $2n/3$ distinct players. A “notarized blockchain” is a blockchain in which every block is notarized.

-

At the beginning of every epoch, a randomly chosen player (the “leader”) proposes a new block for that epoch, extending the longest notarized blockchain that the leader has seen.

-

During an epoch, every player votes for the first new block proposal they see for that epoch, but only if it also extends one of the longest notarized blockchains that the voter has seen.

-

When a player observes, in a notarized blockchain, three adjacent notarized blocks from consecutive epochs, the player finalizes the second block out of the three and its parent chain.

State of Blockchain

Historically, Paxos (1989), PBFT (1999), and their variants have been the mainstream practical approach in distributed consensus. As consensus became more useful, simplifying consensus became a first-order goal, motivating works such as Raft. More recently, the spurt of modern cryptocurrency research has brought with it a leap in understanding of how to construct simple blockchain protocols. These new techniques - which we refer to as the “streamlined blockchain paradigm” - are surprisingly simple and practical, and have the potential to replace prior work in the classroom and in practice.

Casper FFG introduced what are perhaps the first streamlined blockchains, and works such as Hotstuff, PiLi/PaLa, and Tendermint extend it further. Despite this, the literature is scattered and difficult to navigate, which leaves room for a unifying, simple blockchain paradigm. To the best of our knowledge, Streamlet is the simplest blockchain protocol; it is an ideal protocol to teach, implement, and to illustrate just how simple consensus has become, compared with Paxos, Raft, and PBFT.

Streamlet In-Depth

In this section, we dive into the details of the Streamlet protocol; for a formal treatment, see the paper.

The Blockchain Problem

Streamlet solves the following problem – besides the modern name “blockchain”, it was also known as State Machine Replication (SMR) or Byzantine-Fault Tolerance (i.e. PBFT) in the literature. We’ll just call it (permissioned) ‘blockchain’:

-

$n$ players, $f$ of which are byzantine. Honest players follow the protocol, whereas Byzantine players may deviate arbitrarily from the protocol. Assume that $f <n/3$.

-

Players receive signed transactions from the environment and seek to order these transactions into a log, which we call a blockchain, comprised of blocks.

-

(Consistency) Every honest player must finalize prefixes of the same blockchain.

-

(Liveness) If some honest player receives a transaction, that transaction must eventually be finalized by every honest player - ideally in expected constant time when the network is reliable.

Execution Model

We describe a simplified model in which Streamlet operates:

-

Epochs: The protocol runs sequentially in synchronized ‘epochs’ that are 2 seconds long. Every player starts in epoch 0 at the same time, and then after 2 seconds have elapsed, every player enters epoch 1 at the same time, and so forth1.

-

Epoch Leaders: For each epoch, there is a single global ‘leader’ of that epoch, known to all players. We assume the leader is randomly chosen, e.g., with a public hash function.

-

Partially Synchronous Network: The network can at times be unreliable, or adversarial; the protocol must not lose consistency in this case. However, when network conditions are good, i.e., when honest players can communicate with each other within 1 second, the protocol must make progress.

-

Digital Signatures: every vote and proposal is signed by the corresponding player.

Data Structures

Streamlet has only a single message type, a ‘vote’, which is a signature on a block.

-

Blocks: The protocol reaches agreement on ‘blocks’, each of which comprises a set of transactions, and contains a cryptographic hash of a parent chain. Each block thus ‘extends’ and commits to a unique blockchain2, which can be thought of as a history or distributed ledger of transactions.

-

Notarized Blocks: Players can cast ‘votes’ for specific blocks using digital signatures. When a player sees a block with $2n/3$ votes from unique players (where n is the number of total players), the player considers that block ‘notarized’. When every block in a chain of blocks is notarized, the player calls that chain a ‘notarized blockchain’.

Finally, the Protocol

-

At the beginning of each epoch,

Proposal: Let $ch$ denote (one of) the longest notarized chain(s) that the leader has seen so far.

The leader of the epoch aggregates new, unconfirmed transactions, and proposes a new block containing the current epoch number, those transactions, and a hash of $ch$ (colloquially, the new block ‘extends’ $ch$).

-

During each epoch,

Vote: Each player, when it sees a new block proposal for that epoch, votes for it iff it extends (one of) the longest notarized chain(s) the voter has seen thus far. Each player casts at most one vote per epoch.

-

A block is finalized when:

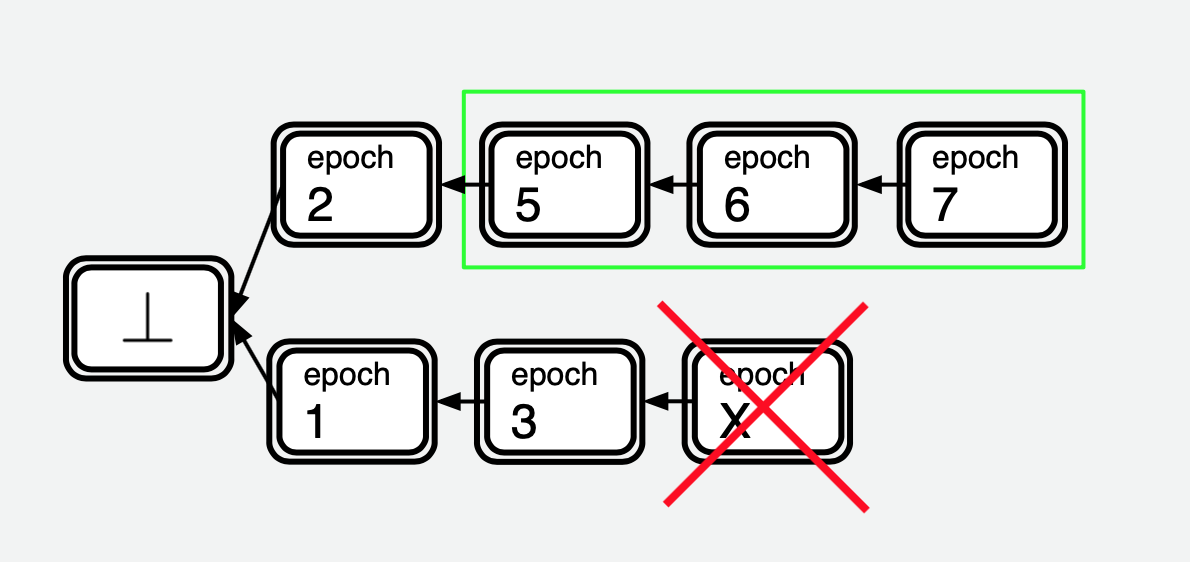

Finalization Rule: On seeing three adjacent blocks in a notarized blockchain with consecutive epoch numbers, a player can finalize (or commit) the second of the three blocks, and its entire prefix chain. We illustrate this pictorially in Figure 1.

Intuitively, if the network delivers messages in 1 second, and if the leader is honest and has an up-to-date view of the blockchain, their block proposal propagates and accumulates votes quickly enough that every player sees a new notarized block by the end of the epoch.

And that’s it!

The entire protocol is “propose-vote-propose-vote-propose-vote…”. There is no other fallback or recovery path like in classical protocols such as PBFT/Paxos!

A Brief Argument for Consistency

Let’s briefly go over why consistency holds in Streamlet - or in other words, why double spending is impossible.

Figure 1 illustrates the scenario in question. A player has seen three consecutive notarized blocks (denoted by the double-lined boxes in the diagram) with epoch numbers 5, 6, and 7. Now the finalization rule can be applied (marked by a green box); so block 6 is finalized by the player, along with its parent chain (blocks 2 and 5).

For consistency, we want to show that no other honest player will finalize a ‘competing’ block (e.g., blocks 1, 3, and $X$). We can show this by showing that block 6 is the unique notarized block at its height, where a block’s height is its distance from the genesis block. In other words, a notarized block $X$ cannot exist. Since block 6 is unique at its height, then every longer notarized chain must contain block 6, and thus blocks 2 and 5. This excludes blocks 1 and 3 from ever being included in a longer notarized blockchain; thus they can never be finalized.

Why can’t a notarized block $X$ exist? Note that if a notarized $X$ exists, then a majority of honest players must have seen a notarized block 3 by the end of epoch $X$. We can derive a contradiction. First, note that there can be at most one notarized block for each epoch number (since players vote for a single block per epoch). As a result, $X$ must be less than 5 or greater than 7.

-

Case 1: $X<5$: since block $X$ got notarized, it means that more than $n/3$ honest players, denoted $S$, must have voted for block $X$ and not only so, at the time of this voting (that is, during epoch $X < 5$), they must have observed block 3 notarized. Now the honest players in $S$ will not vote for block 5 during epoch 5, since it fails to extend a longest notarized chain seen, which is block 3 or longer. Since $f <n/3$, this means that block 5 can never get notarized. This leads to a contradiction.

-

Case 2: $X > 7$: since block 7 is notarized, more than $n/3$ honest players (denoted the set S) must have seen a notarized block 6 by the time they vote for block 7 (i.e., by the end of epoch 7). As a result, by the time epoch $X$ comes around, the set $S$ of players have seen block 6 notarized and will not vote for block $X$, since $X$ now fails to extend the longest notarized chain seen (which is block 6). Then $X$ cannot accumulate $2n/3$ votes, so $X$ cannot be notarized, which is a contradiction.

This argument generalizes to arbitrary epoch numbers $e, e+1, e+2$ as opposed to epochs 5, 6, 7, which completes our sketch of the consistency argument.

Observe that the consistency proof does not require any message delivery guarantees by the network. In other words, even when there can be arbitrarily bad network partitions, we still guarantee consistency (however, during network partitions progress can halt). Again, this model is called partially synchronous.

Liveness

In our paper, we show that when network conditions are good, i.e., when honest players can deliver messages to each other within 1 second, then Streamlet makes progress whenever there are five consecutive epochs whose leaders are all honest. At a high level, the first couple “honest” epochs may be needed to undo any bad effect from bad leaders from previous epochs. We then top that off with three honest epochs to create three consecutive notarized blocks (with consecutive epochs), after which a new block (from an honest proposer) is finalized in the view of every honest player.

The liveness argument is slightly more subtle than the consistency argument but nonetheless still quite simple. We refer the reader to our full paper for the liveness argument.

Conclusion

We hope that this post is a useful exposition of what might be the simplest blockchain protocol known. We think that Streamlet has the potential to unify existing protocols and perhaps become a de facto standard.

We thank Decentralized Thoughts for the opportunity to write this blog post, and Ittai Abraham for insightful and thoughtful feedback on an initial draft.

Please leave comments on Twitter.

-

The length of each epoch should be configured to match the time it takes for a message round trip when network conditions are good. We guarantee consistency even when network conditions are arbitrary but guarantee liveness when network conditions are good. ↩

-

With high probability, using a collision resistant hash function family. ↩