Blockchain databases are storage systems that combine properties of both blockchains and databases like decentralization, tamper-resistance, low query latency, and support for complex queries. As they gain wider adoption, concerns over the confidentiality of the data they manage will increase. Already, several projects use blockchains to store sensitive data like electronic healthcare and financial records, legal documents and customer data.

In this post, we discuss our new paper Encrytped Blockchain Databases in which we design end-to-end encrypted blockchain databases to support decentralized applications that need to store and query sensitive data. In particular, we focus on what we call blockchain encrypted multi-maps (EMM) which can be used to instantiate various kinds of NoSQL blockchain databases like key-value stores or document databases.

The area of cryptography that focuses on the design of end-to-end encrypted databases and, more generally, on the problem of searching on encrypted data is called encrypted search. For an introduction to the area, please see this series of blog posts from the Encrypted Systems Lab at Brown University. The 5th post, in particular, describes a construction of a standard/centralized EMM (which in the post is called an encrypted database (EDB)).

Encrypted Multi-maps

NoSQL databases have recently become prominent in the database industry due to their simplicity, scalability and high-performance guarantees. A variety of NoSQL databases, like key-value stores (e.g., DynamoDB) and document databases (e.g., MongoDB), can be instantiated with a multi-map data structure. Multi-maps are a generalization of dictionaries that map labels to a tuple of values1. They support get and put operations which, given a label, can either store or retrieve the tuple of values associated with the label. An encrypted multi-map (EMM) is an end-to-end encrypted multi-map that supports get and put operations but over encrypted data. Since multi-maps can be used to represent NoSQL databases, designing blockchain encrypted NoSQL databases is essentially the same as designing blockchain EMMs.

Legacy Friendliness

There are two main approaches to design a blockchain EMM. The first is to design a new blockchain with dedicated support for EMMs. This approach has the advantage that the EMM and blockchain can be co-designed to optimize performance. The second approach consists of designing a solution that is legacy friendly in the sense that it can be used on top of pre-existing blockchains. The advantage of this approach is that the blockchain EMM can be built on top of multiple platforms and there is no need to set up a new blockchain. There are, however, a few challenges with the second approach:

-

How do we store data structures on a blockchain? In particular, how can we store an encrypted multi-map data structure? Most existing blockchains are designed to store financial transactions or the state of smart contracts but not arbitrary data structures.

-

Since blockchains are tamper-resistant by design, how can we update the EMM – in particular, how can we add/delete data from it?

One naive solution for (2) is as follows: on every update, we can read the entire EMM from the blockchain, make the necessary changes, and write it back as a completely new EMM. This is an ideal solution for query correctness since every query always reads from an up-to-date EMM. This solution, however, is extremely inefficient for update operations since the entire structure has to be read and written back for every single update operation. Therefore, one also needs to think about the following third challenge:

- How to design an efficient blockchain EMM with respect to query and update complexity?

Before describing our blockchain EMM constructions, let us discuss the 1st challenge – the 2nd and 3rd challenges are trickier, so we will tackle them when detailing the constructions themselves.

Storing Arbitrary Data Structures on Blockchains

Most blockchains (e.g., Bitcoin, Ethereum, Algorand) allow users to store arbitrary data in their transactions. Since only a limited amount of data can be stored in a single transaction, large data structures have to be split over multiple transactions. The question then becomes:

How can we link these transactions together to build an arbitrary data structure?

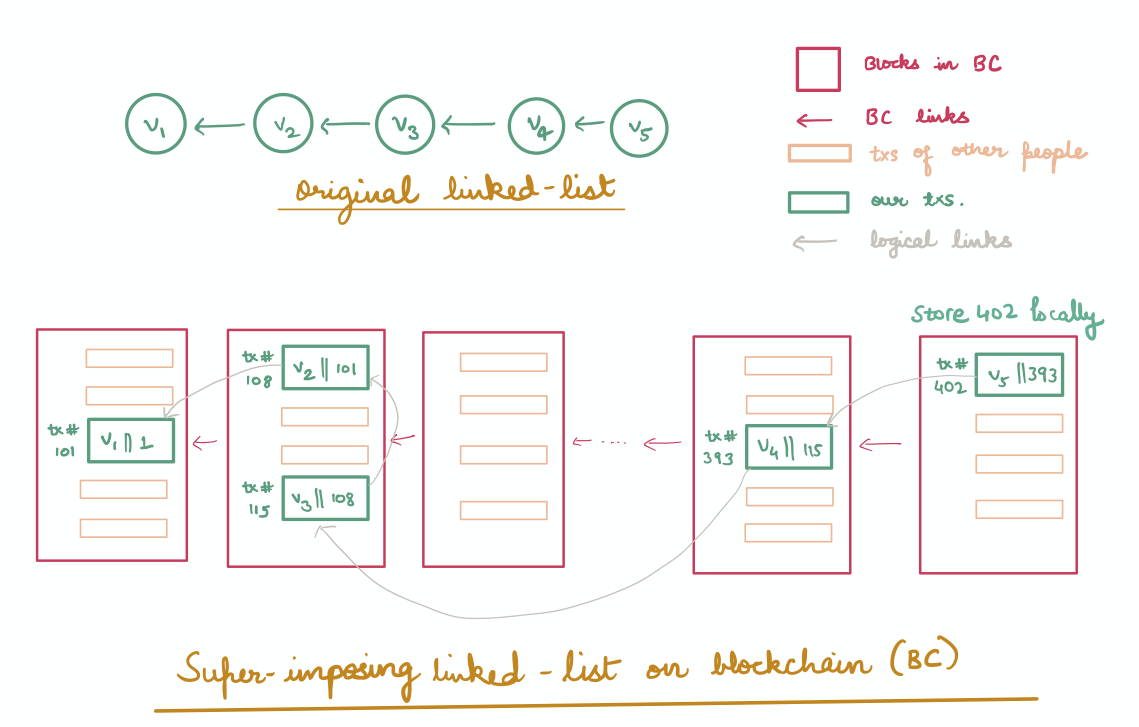

To answer this question, notice first that transactions can be linked by storing the “addresses” of previous transactions in newer transactions. Leveraging this property, we are going to superimpose a data structure on top of the blockchain in a way that we can update and query the data structure and without any modification to the backend (the blockchain). In the following, we provide a simple example of how to superimpose a linked list. To store a list with values $V = (v_1, …, v_n)$ on the blockchain, we do the following (refer to Figure 1 for an illustration of this process):

- Concatenate each value $v_i$ with the address $r_{i-1}$ of the previous transaction which stores $v_{i-1}$.

- Create a new transaction with $v_i || r_{i-1}$ and send it to the blockchain. This generates $r_i$, the address of this new transaction.

- Repeat this for all the values.

- Finally, store the address $r_n$ of the last transaction with the client.

To read the values, do the following:

- Send $r_n$ to the blockchain to recover the value $v_n$ and the address $r_{n-1}$.

- Then use $r_{n-1}$ to recover $v_{n-1}$ and $r_{n-2}$.

- Continue this process until all the values have been read.

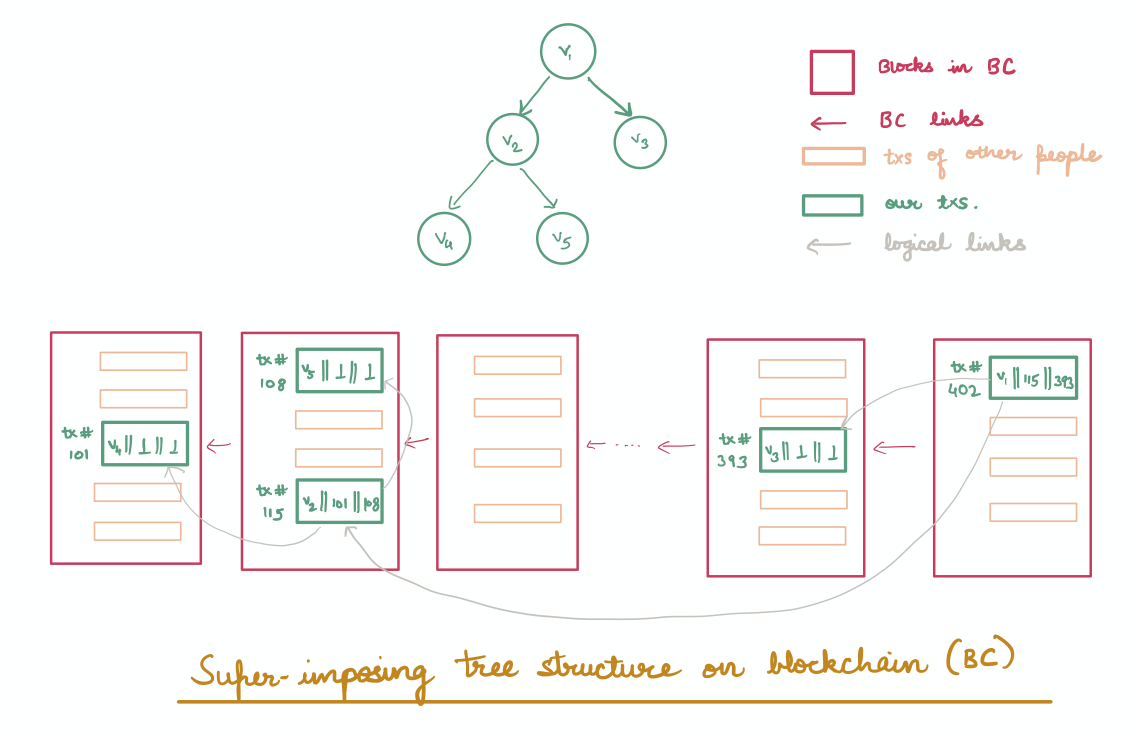

Similarly, we can superimpose more complex data structures on a blockchain such as a binary trees. This can be done by concatenating two addresses to each value: one for its left child and one for its right child. This is illustrated in Figure 2.

Limitations of smart contracts

For blockchains that support smart contracts, an alternative approach could be to store an entire data structure as the state of a smart contract and to implement the query and update operations as a smart contract. Unfortunately, there are two main limitations to this approach. First, it is not general-purpose, since (1) many blockchains do not support smart contracts (e.g Bitcoin), and (2) many smart contract platforms do not maintain state across transactions (e.g., Algorand). The second limitation is related to the cost of using such platforms. In fact, smart contract platforms require payment not only for storing data and code but also for executing code; and the more complex the code is, the higher the cost. Note that the first approach where we superimpose a data structure on top of the blockchain is not only general, but also entails lower cost since we can store data in transactions as opposed to smart contracts and don’t need to execute any code on the blockchain.

In the next part of the series, we describe three schemes to store dynamic EMMs on blockchains, each of which achieves different tradeoffs between query, add and delete efficiency.

Please leave comments on Twitter.

-

We reserve the term key to refer to cryptographic keys. ↩