If you ever tried to understand Bitcoin, you’ve probably banged your head against the wall trying to understand what is a cryptographic hash function? The goal of this post is to:

- Give you a very simple mental model for how hash functions work, called the random oracle model

- Give you three key applications of hash functions:

- Downloading files over the internet

- The proof-of-work at the core of Bitcoin

- Commitments and coin flipping

We’ll refer to cryptographic hash functions simply as “hash functions” in this post.

What this post is NOT

This post will NOT explain to you how a concrete hash function like SHA256 works. Explaining the internals of SHA256 (or any other hash function) would be like explaining to a new driver how the engine of a car works before teaching them how to drive it: most people would get bored fast and lose interest.

Also, this post will NOT explain to you how Bitcoin works, nor how its proof-of-work consensus works! Instead, we’ll explain the proof-of-work scheme itself, which is a core component of Bitcoin and its consensus algorithm. (For that, you could go here.)

Finally, this post is in no way a formal treatment of hash functions and their many interesting properties. At the same time, this post tries not to oversimplify hash functions either. Our hope is that, by the end of the post, you’ll be curious enough to dig deeper into hash functions yourself. (As a starting point, use the references at the end1$^,$2$^,$3$^,$4$^,$5.)

A hash function is a “guy in the sky,” flipping coins

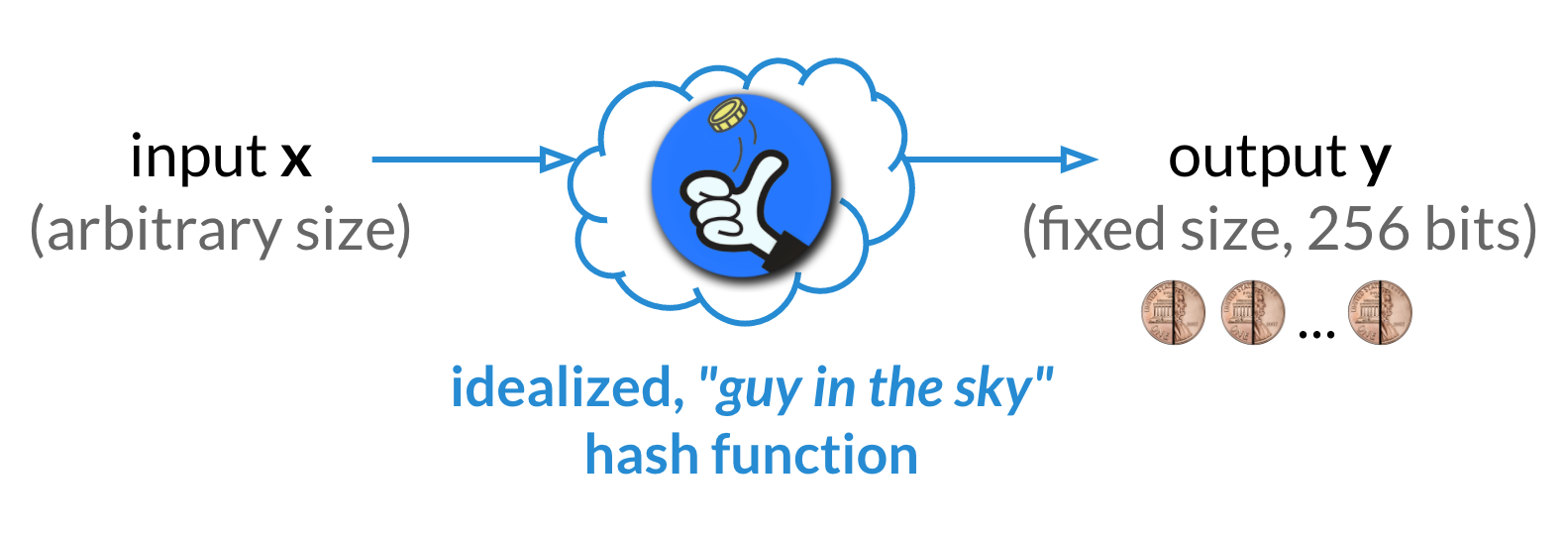

My favorite analogy for how a hash function works is the “guy in the sky” analogy6, as illustrated below.

Here’s the analogy. There’s a “guy in the sky.” You can give him an arbitrarily-sized input $x$. In return, he’ll give you a fixed-size, “random looking” output $y$ back. Super-importantly, if you ever give him $x$ again, he’ll give you that same $y$ back! How does he do it?

When he gets your input $x$, he initially ignores it! Then, he flips 256 coins, getting a sequence of 256 random bits (i.e., ones and zeros), denoted by $y=\langle y_1, y_2, \dots, y_{256}\rangle$. Next, he forever remembers that your input $x$ maps to output $y$ by writing down $(x,y)$ in his magic scroll. This way, if you ever give this “guy in the sky” the same input $x$, he will give you back the same output $y$ (rather than flip new coins and give you a new random 256-bit output $y’\ne y$).

That’s it! The simplest way you can think of a hash function is as a “guy in the sky” who flips coins for each input you give him, remembering what coins he got for every input you gave him, just in case you give him that input again. Since inputs are arbitrarily-sized and outputs are fixed-size, a hash function effectively “compresses” the input. However, the key insight you should keep in mind is that this “compression” is done by picking the output randomly, which has many interesting implications! (Well, the devil is in the details, but for now this intuition is good enough.)

A hash function is a “random oracle”

Now, let’s take a step away from mythical creatures in the sky and a step closer towards formalizing hash functions.

What we are saying is that a hash function is a kind of “algorithm” or “oracle” that “compresses” inputs to outputs as follows:

- You give it an arbitrarily-sized input.

- It checks if it already generated 256 random bits for that input.

- If so, it gives you those 256 random bits as output.

- If not, it flips 256 random coins, associates them to this input, and gives you the coins as output.

This idealization of hash functions is called the random oracle model1. Simple enough, no? Get an input, flip some coins for it (unless already done so in the past) and return those coins!

Limitations of the random oracle model

It turns out the random oracle model is incredibly useful to reason about the properties of hash functions. It’s also a very simple mental model for how a hash function works!

Of course, in practice, we need to actually build an algorithm that behaves like this “guy in the sky” or this random oracle. Unfortunately, this is impossible.

Kthxbye, end of post!

Just kidding. Fortunately, in practice, we can circumvent this impossibility in a few ways. For example, in some applications, we settle for hash functions whose outputs are not random but have other useful properties that are implied by the random oracle model. One such property is collision-resistance, which says it is infeasible to find two inputs $x\ne x’$ such that their outputs $y$ and $y’$ are equal. (We’ll touch upon this later.) In other applications, cryptographers simply “hope” that replacing the idealized random oracle with a concrete hash function like SHA256 will not lead to security breaks in practice.

Note: There is reason to be skeptical of such hope. We know that, for certain cryptosystems proven secure with a random oracle, replacing the random oracle with any concrete hash function makes them insecure5.

Hash functions as mathematical functions

We’ve established that a hash function can be thought of as a random oracle that, given some input $x\in \{0,1\}^*$ (i.e., an arbitrarily-sized sequence of bits) returns a “random,” fixed-size output $y\in \{0,1\}^{256}$ (i.e., 256 bits) and will always return that same $y$ given that same $x$ as input. (We assume the output size is 256 bits. We’ll explain later why.)

Formally, we can define a hash function as a mathematical function $H : \{0,1\}^* \mapsto \{0,1\}^{256}$. We use $H(x) = y$ to denote that $y$ is the output of $H$ on input $x$.

Collision-resistance and the pigeonhole principle

This definition brings one limitation of hash functions into light, which is worth discussing now.

Note that a hash function maps the set of all arbitrarily-sized binary strings (which is of infinite size) to the set of binary strings of length 256 (which is of size $2^{256}$). For the mathematically-inclined, the “pigeonhole principle” immediately tells us that, as a consequence, there must exist two inputs $x\ne x’$ such that $H(x)=H(x’)$. Such a pair $(x,x’)$ is called a collision and can be disastrous in many applications of hash functions, as we’ll discuss later.

For the less mathematically-inclined: It’s as if we have an infinite amount of puppies and $2^{256}$ people who want to pet them. This tells us that, if all puppies are to be petted by someone, then someone has to pet more than one puppy! In other words, there will be two puppies $x$ and $x’$ that are petted by the same person $y$7$^,$8.

Restated formally, because the domain $\{0,1\}^*$ of $H$ is larger than the range $\{0,1\}^{256}$ of $H$, there must exist two inputs $x\ne x’$ that map to the same output $y=H(x)=H(x’)$.

Fortunately, in the random oracle model, one can show that finding such a collision is infeasible, requiring on average $2^{128}$ hash function invocations, which is an astronomical number that is outside the realm of practicality. (We’ll describe this collision-finding algorithm, which is called the birthday attack, in another post.) Even better, as cryptographers, we know how to construct collision-resistant hash functions from hard computational problems such as computing discrete logarithms.

What can I do with a hash function?

By now, you know that a hash function “compresses” an arbitrarily-large input to a fixed-size output, which is uniquely determined by flipping some coins. Next, let’s see what a hash function is useful for.

Downloading files correctly over the Internet

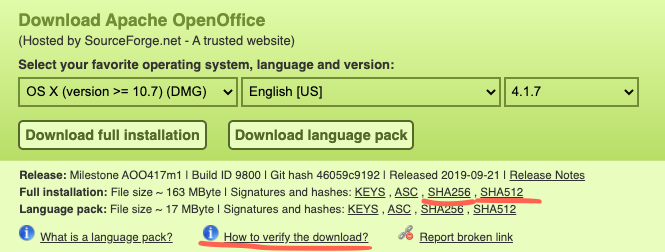

Did you ever notice how sometimes websites display a hash next to a file after you click the download button? For example, this is what you see if you try to download Apache OpenOffice:

What is this all about? It’s about preventing attackers from modifying the files you’re downloading!

The Apache OpenOffice installer is a large, frequently-downloaded file. As a result, instead of being hosted on the Apache website itself, it might be hosted on external, insecure FTP or HTTP servers (which might be cheaper and/or faster to download from). However, since FTP and HTTP channels are not secure, this means that when a user downloads the file, an attacker might maliciously modify it! For example, he might replace the file with a virus.

To deal with such attacks, the secure Apache website allows the user to first download the hash $h$ of the OpenOffice installer file $f$. In other words, the user can correctly obtain $h=H(f)$. Note that the attacker cannot maliciously modify the hash $h$, since the Apache website uses HTTPS. This way, the user is guaranteed to have the correct hash $h$ of the installer $f$ they are trying to download.

Next, the user can download the installer file $f$ over the insecure FTP or HTTP channel. However, the attacker might replace $f$ with $f’$ by tampering with the channel. Fortunately, the user can easily check that $H(f’) \ne h$, so they can detect the attack.

But what if the user downloads $f’$ with $H(f’) = h$? In other words, can the attacker come up with a file $f’\ne f$ but with $H(f’) = H(f) = h$? This would trick the user into downloading the wrong file $f’$! The short answer is “no:” since the hash function is collision resistant, the user can be certain that $f’ = f$, so he downloaded the file he intended to. We explain why below.

Why the adversary can’t replace $f$ with a different file $f’$

The adversary’s goal is to trick the user, who has the hash $h$, and give him a different file $f’\ne f$ such that $H(f’)=H(f)$. Let’s see why he can’t do this.

If we think of $H$ as a random oracle, what can the adversary do to find such an $f’$? The adversary can only query $H$ at whatever points he might think will return $H(f)$. But since the random oracle $H$ returns random coin flips for whatever input the adversary provides, this means the adversary has no particular strategy other than brute-force for finding an $f’$ with $H(f’)=H(f)$.

With a little probability theory, one can show that the adversary has to query $H$ around $2^{256}$ times to actually find such an $f’$. Since this is outside the realm of practicality, our file downloading scheme is considered secure!

Remark: In the attack above, the attacker is trying to find a collision $f’$ w.r.t. a particular fixed file $f$. However, depending on the application, the attacker might have more “freedom.” Specifically, the attacker could try and find any collision $(f,f’)$ in the hash function. This would take him a smaller, but still astronomical, amount of time: $2^{128}$ rather than $2^{256}$ hash function invocations. If the attacker is successful, he could trick users who have the same $h$ into downloading different files. (As an exercise, try and think of application scenarios where that might be problematic!)

Proof of work

Suppose you want to convince me you’ve done some amount of computational work. Specifically, let’s assume you want to convince me you’ve computed roughly $n$ different hashes by calling $H$ on $n$ different inputs. Such a protocol is called a proof of work and you can leverage the random oracle nature of hash functions to implement it!

An inefficient protocol

Note that if I send you a random value $r$, and you give me back $y=H(r)$, I can check that you computed $H(r)$ correctly by recomputing it myself. But it seems like in order to check that you’ve computed $n$ hashes, I have to give you $n$ different $r$’s and re-compute the $n$ hashes you computed too. While this protocol could be thought of as a “proof-of-work,” it’s not very efficient for me to check that you’ve done the work. Can I verify your work faster?

An efficient, probabilistic protocol

Let’s come up with a more efficient protocol for convincing me you’ve computed roughly $n=2^k$ different hashes. Here $k$ can be very large (e.g., $k=60$), since my goal is to really make sure you take a long time to compute these $n=2^k=2^{60}$ hashes. This protocol is probabilistic in the sense that, with very small probability, you might trick me into thinking you’ve computed $n$ hashes when in fact you’ve computed much fewer. (In contrast, in the inefficient protocol, I was always certain you computed exactly $n$ different hashes.) The probabilistic nature is not a big deal in certain applications (e.g., Bitcoin), so we accept it.

First, some intuition!

Since $H$ can be viewed as a random oracle, we know that a hash $H(r)$ is obtained by flipping 256 random coins. For the mathematically-inclined, we also know that, if we want the first $k=60$ coins flips to be all “heads”, then we have to flip these 256 random coins around $2^{60}$ times. For the less mathematically-inclined, if you have 1 in 3 chances to win a teddy bear in a game, you kind of know that if you play around 3 times you’re likely to win. Similarly, there are 1 in $2^{60}$ chances for the first $k=60$ coins to be all “heads”, which is why you have to flip the coins around $2^{60}$ times.

So, it takes $2^{60}$ tries to get 256 random coins where the first $60$ coins all heads. That’s like saying it takes around $2^{60}$ hash computations to get a hash whose first $60$ bits are equal to zero!

That’s starting to look like a proof of work!

In other words, say I give you a random value $r$ and you give me a pair $\langle i, h_i = H(i \mid r)\rangle$, where $h_i$ has the first $k=60$ bits all set to zero and $|$ denotes concatenation. Then, I can easily check that $h_i = H(i \mid r)$ using only one hash computation and I’ll be pretty sure that it took you around $n=2^k=2^{60}$ hash computations to find such an $i$. I say “pretty sure” because it’s also possible you got very lucky and the first $i$ you picked happened to give you an $H(i \mid r)$ with the first $k=60$ bits zero. (But the probability of that happening is pretty low, around $1/2^{60}$.)

Why you can’t easily trick me when you haven’t done the work

Your goal, as the adversary, is to find an $i$ such that $h_i = H(i \mid r)$ has $k$ leading zeros, but you want to do so while computing much fewer than $2^k$ hashes.

Once again, since $H$ is a random oracle, your only strategy is to simply query $H$ at inputs of the form $i\mid r$. Each query gives you an output $h_i$ whose probability of having $k$ leading zeros is $1/2^k$. As a result, to ensure you get such an $h_i$ you have to “try” computing different $h_i$’s around $2^k$ times (for those who are into probability theory, this around is essentially concentration of measure).

Why is the probability of a hash having $k$ leading zeros equal to $1/2^k$? Because $H$ is a random oracle and each bit of the output has probability $1/2$ of being a zero and $1/2$ of being a one! As a consequence, the probability that you get $k$ consecutive zeros is $\underbrace{1/2 \cdot 1/2 \cdot \cdots \cdot 1/2}_{k\ \text{times}}=(1/2)^k = 1/2^k$.

Commitments and coin flipping

Suppose you and your friend are trying to decide whether you should go to the beach or not. You want to swim, so you say “beach!” but your friend is not too excited about the hot summer days, so they say “no beach!” Obviously, one thing you could do is end the friendship immediately. But as a middle ground, you propose flipping a coin to decide! Unfortunately, your friend is far away, so you have to do this remotely. How might you two do this without any shenanigans?

If you flip the coin and tell the outcome to your friend, you might as well lie and tell them the outcome was “beach!” However, your friend is smart and they wouldn’t believe you. Similarly, why would you believe them if they flipped a coin and told you the outcome?

Flip your coin and lock it away!

One possible solution is for both of you to flip your own coin and then combine your two coins (somehow) into a flipped coin that is “fair”: each coin side has $1/2$ chance of occurring. As an (impractical) example, you could flip your own coin, write the result on a piece of paper and put it in a locked box. Your friend would do the same using their own coin and locked box. Think of the locked box as a commitment: it hides the outcome of the coin flip while binding you to it, since you can’t change your mind about it once you’ve given the locked box to your friend. To reveal your coin flip, you would give your friend the key to the box. They would do the same for you. (We simplify and assume both of you always give each other the keys!)

Now, both of you will have two coin flip outcomes, which you can combine to simulate a “joint” coin flip as follows. If both coins are “heads” or “tails”, the joint coin is “heads” or “tails,” respectively. If one of the coin is “tails” but the other is “head”, the joint coin is “tails.” This “joint” coin will be “fair” as long as one of you flipped their coins fairly.

Committing to your coin flips

The remaining question is how can we build such a commitment scheme that hides the coin flip and binds you to it. Note that if we simply hash the coin outcome as, say, $h = H(\text{“heads”})$ and let $h$ be the commitment, then this is not hiding. Specifically, if you give your friend the hash $h$, they can easily check if $h$ is equal to $H(\text{“heads”})$ or to $H(\text{“tails”})$, so they will know your coin flip. On the other hand, $h$ is binding since, once you’ve given $h = H(\text{“heads”})$ to your friend, you cannot later pretend that $h = H(\text{“tails”})$, since the probability of that happening is $1/2^{256}$.

The next observation is we can get hiding by hashing as $h=H(\text{“heads”}\mid r)$ rather than as $h=H(\text{“heads”})$, where $r$ is a random 256-bit string. Now, your friend cannot easily check if $h$ is the hash of “heads” or “tails” because they do not know $r$. So this scheme hides the coin! Furthermore, this scheme remains binding since, to break binding, you would have to find $r_1, r_2$ such that $H(\text{“heads”}\mid r_1) = H(\text{“tails”} \mid r_2)$, which would be a collision in the hash function. Fortunately, we know collisions can be found with probability $1/2^{128}$.

The fact that such collisions exist (but are infeasible to find) also hints that the scheme is hiding. In other words, existence of collisions implies you can reveal a different coin flip and randomness that has the same hash $h$. Therefore, $h$ cannot leak anything about the hashed input.

Conclusion

I promised this post would give you two things.

A very simple mental model for how hash functions work

A hash function is a random oracle: it takes an arbitrarily-sized input $x$, flips 256 coins $y=\langle y_1, y_2, \dots, y_{256}\rangle$, “remembers” $x\mapsto y$, and from now on always returns $y$ (i.e., 256 bits) on input $x$.

Applications of hash functions

Download integrity: Users can verify the integrity of a file downloaded over an insecure channel against the file’s hash, which the user is assumed to have (somehow) obtained correctly.

Proof-of-work: You can convince me you’ve computed around $2^k$ hashes by giving me a number $i$ and a hash $h_i = H(i \mid r)$ with $k$ leading zeros, where $r$ is a random 256-bit string I gave you first.

Commitments: You can compute a commitment $h = H(m\mid r)$ to a message $m$ using some randomness $r$ you generated. Anybody who receives the commitment $h$ does not learn anything about $m$ until you reveal $r$ to them. On the other hand, you cannot reveal a different $m’\ne m$, so you have bound yourself to $m$ by giving $h$ away. This is the equivalent of a digital lock box that stores the message $m$ while hiding it until you choose to open the box. A key application of commitments are coin-flipping protocols (with some caveats).

What is next? Next, we hope to give you a formal model of hash functions, introduce you to Merkle hash trees and then reduce Merkle hash tree security to the collision-resistance of hash-functions.

Acknowledgment. We would like to thank Ittai Abraham for his help on this post!

References

-

Random Oracles Are Practical: A Paradigm for Designing Efficient Protocols, by Bellare, Mihir and Rogaway, Phillip, in Proceedings of the 1st ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security, 1993, [URL] ↩ ↩2

-

Introduction to Modern Cryptography, by Jonathan Katz and Yehuda Lindell, 2007 ↩

-

The Random Oracle Model: A Twenty-Year Retrospective, by Neal Koblitz and Alfred Menezes, in Cryptology ePrint Archive, Report 2015/140, 2015, [URL] ↩

-

Cryptographic Hash-Function Basics: Definitions, Implications and Separations for Preimage Resistance, Second-Preimage Resistance, and Collision Resistance, by Phillip Rogaway and Thomas Shrimpton, in Cryptology ePrint Archive, Report 2004/035, 2004, [URL] ↩

-

The Random Oracle Methodology, Revisited, by Ran Canetti, Oded Goldreich, Shai Halevi, in Cryptology ePrint Archive, Report 1998/011, 1998, [URL] ↩ ↩2

-

Obviously, this could’ve been a “gal in the sky” or a “person in the sky,” but “guy in the sky” rhymes better! ↩

-

In fact, each person will pet an infinite amount of puppies, which incidentally is the most blissful thing I can imagine right now! ↩

-

Henceforth, everybody shall stop using the Pigenhole Principle and adopt this more modern Puppy Petting Principle, which has the advantage of both filling your heart with joy and your mind with mathematics. ↩