An important property satisfied by any Byzantine fault tolerant consensus protocol is agreement, which requires non-faulty replicas to not decide on conflicting values. Depending on the network model, typical consensus protocols tolerate only a fraction of Byzantine replicas. In particular, under partial synchrony or asynchrony, no consensus protocol with $n$ replicas can tolerate more than $n/3$ Byzantine faults. If the number of Byzantine replicas exceed this number, the protocols do not provide safety (or liveness).

In a recent work called BFT Protocol Forensics, we focus on “the day after”: events after $\geq n/3$ Byzantine replicas have successfully mounted a safety attack. Specifically, we focus on providing forensic support to identify the replicas that acted maliciously. Any protocol with strong forensic support should ideally meet three goals:

- Ability to identify as many replicas that act maliciously with an irrefutable cryptographic proof of culpability

- Availability of the culpability proof with as many replicas (witnesses) as possible

- Identification should be conducted as distributedly as possible, i.e., with little or no communication between replicas

The notion of accountability was introduced in seminal works such as PeerReview, and, more recently, the Casper protocol was designed with accountability as a primary consideration. In our work, we show that many existing partially synchronous protocols and asynchronous protocols such as PBFT, HotStuff, and VABA have strong forensic support. In particular, if $t < n/3$ denotes the maximum number of Byzantine faults tolerated by the protocol, and there are $f > t$ Byzantine faults in the system, then for all of these protocols,

- we can identify $\geq t+1$ Byzantine faults,

- where $2t+1-f$ honest replicas can act as witnesses,

- and the proof can be obtained by communicating with just one of these witnesses.

In this blog post, we focus on discussing forensic support for the HotStuff protocol.

Recap on HotStuff

The Basic HotStuff protocol proceeds in a sequence of views where each view adopts a 3-round voting mechanism: the leader proposes a value and all replicas participate in 3 rounds of voting. In each of these rounds, the leader collects $2t+1$ votes and aggregates them into a quorum certificate. The quorum certificates in 3 rounds are denoted by prepareQC, precommitQC, and commitQC respectively. These quorum certificates play an important role in the protocol as follows:

- When a leader proposes, it needs to propose the value corresponding to the highest prepareQC it has received where highest prepareQC is a QC from the largest view.

- When a replica receives a precommitQC for value $v$ in view $e$, it locks on the tuple of (view, value), i.e., $(e,v)$.

- When a replica receives a proposal of value $v$, it votes only if it locks on $v$ except when the proposed prepareQC’s view is higher than its locked view.

- At the end of each view, every replica reports its latest prepareQC to the next leader.

- When a replica receives a commitQC, it commits on the value.

Safety within a view

HotStuff ensures that an honest replica only votes once in any round of voting. Therefore, when the adversary does not corrupt more than $t$ replicas, there cannot be two conflicting commitQCs within a view, since two conflicting commitQCs indicate $t+1$ replicas vote for two conflicting values, which means $t+1$ replicas are corrupted.

When the adversary corrupts $\geq t+1$ replicas, they can vote for two conflicting values, $v$ and $v’$. Let us split $2t$ honest replicas into two sets $P$ and $Q$. If the leader is corrupted, it can equivocate to replicas in $P$ and $Q$. As a result, replicas in $P$ vote for $v$ and replicas in $Q$ vote for $v’$. Two conflicting values thus both get $2t+1$ votes, which are enough to form two conflicting commitQCs.

Safety across views

When the adversary does not corrupt more than $t$ replicas, HotStuff ensures safety across views by the use of locks and the voting rule. If a commitQC for value $v$ exists in view $e$, at least $2t+1$ replicas lock on $(e,v)$. In views higher than $e$, there could not be a prepareQC on values other than $v$, since such a quorum certificate means $t+1$ replicas (among $2t+1$ replicas) who lock on $(e,v)$ vote for value $v’\neq v$.

When the adversary corrupts $\geq t+1$ replicas, these replicas can vote for a conflicting value $v’$ despite having a lock on $(e,v)$. Again, let us split $2t$ honest replicas into two sets $P$ and $Q$. Replicas in $P$ vote for value $v$ in view $e$ and also lock on it whereas replicas in $Q$ are not aware of value $v$ or the corresponding lock. Then in some higher view, a leader may propose an outdated prepareQC with a conflicting value $v’$. Replicas in $Q$ are not aware of the lock on $(e,v)$ so they can vote for $v’$ along with the $t+1$ corrupted replicas also vote for $v’$ (and violate the voting rule). As a result, the leader can collect $2t+1$ votes to form a prepareQC in the higher view. This prepareQC is sufficient to unlock any honest replica and subsequently replicas can commit a conflicting value.

Forensic Support for HotStuff

In the above examples of safety violation, we observe that the corrupted replicas must send certain messages in order to break safety: 1) to break safety within a view, corrupted replicas vote for two conflicting values in the view, 2) to break safety across views, they vote for a conflicting value despite having a lock (and prepareQC) on a different value (thus violating the voting rule). Those messages are signed by their secret keys hence can serve as irrefutable evidence of their misbehavior. In addition, no honest replica will vote twice within a view or violate the voting rule, therefore we will only hold corrupted replicas culpable.

With the above intuition, we have a forensic protocol for HotStuff Byzantine Agreement protocol:

- To identify disagreement and trigger the forensic protocol, two conflicting commitQCs need to be provided to the forensic protocol as input.

- If two commitQCs are within a view, the replicas who vote for both commitQCs are corrupted replicas.

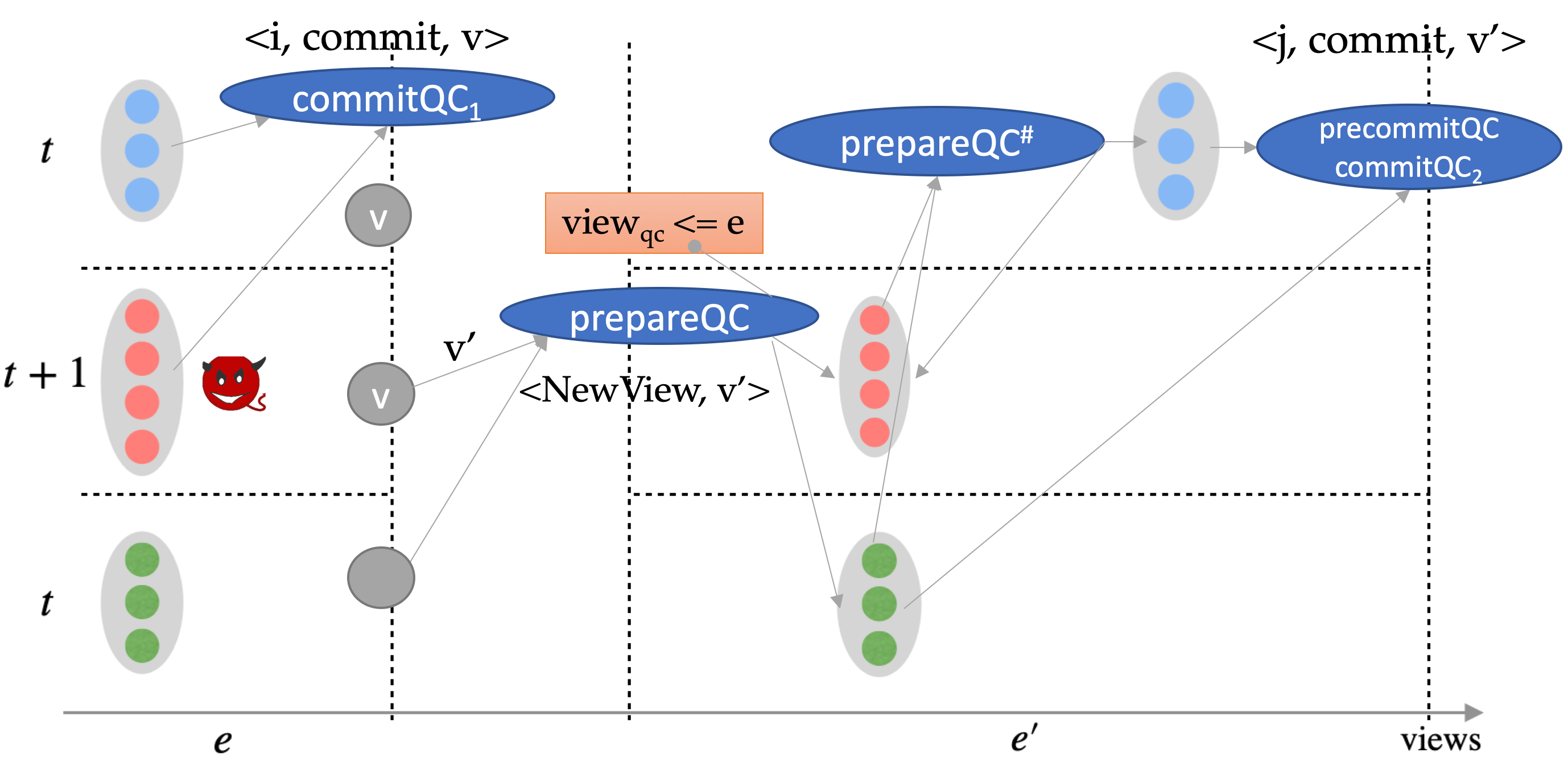

- If two commitQCs are across views, we denote by commitQC1 the lower one and commitQC2 the higher one. We query all replicas for a prepareQC (denoted by prepareQC#) such that it is later than commit1, its value $v’$ conflicts with the value $v$ of commitQC1, and the previous prepareQC for $v’$ in the proposal is no later than commitQC1. The replicas who vote for commitQC1 and prepareQC# are corrupted replicas.

Recall that our goal was to (i) identify as many Byzantine replicas as possible, (ii) while having a large number of witnesses, and (iii) obtain the proof from querying as few witnesses as possible. There are $n=3t+1$ replicas in the system. In both of the cases, the process of identifying culpable Byzantine replicas involve performing appropriate quorum intersections: since two quorums of $2t+1$ replicas intersect in $t+1$ replicas, we are able to identify $\geq t+1$ Byzantine replicas. Who are the witnesses? For conflicting commits within a view, the commitQCs themselves can prove culpability. For conflicting commits across views, honest replicas having access to prepareQC# are witnesses. It turns out that the existence of commit2 implies that $2t+1$ replicas should have received prepareQC#, out of which $f$ of them are Byzantine. The remaining $2t+1-f$ replicas can act as witnesses. This also implies that the forensic support holds only when $f < 2t+1$; when the number of Byzantine replicas are higher, we may have no witnesses.

The below figure shows an example attack which results in conflicting commits across views. In Figure1, $t+1$ red replicas are corrupted. An honest node $j$ commits $v$ in view $e$ on receiving commitQC1. The formation of commitQC1 indicates blue replicas are locked on $(v,e)$. Some views later, a malicious leader proposes a different value $v’$ and sends the proposal to another set of honest replicas. According to the voting rule, green replicas will vote and a higher prepareQC# for $v’$ is formed. After two rounds of voting, $v’$ is committed by another honest replica $j$. In this example, red replicas are held accountable since they vote for both commitQC1 and prepareQC#. And blue nodes have access to the evidence.

Subtleties and implementation details

Observe that our constraint for prepareQC# was that it should be “later than commit1, its value $v’$ conflicts with the value $v$ of commitQC1, and the previous prepareQC for $v’$ in the proposal is no later than commitQC1”. This step identifies the first time a conflicting value received a prepareQC. Ensuring the “first time” constraint is important since after that, all honest parties can legitimately vote on the conflicting value (and they should not be held liable for it). It turns out that obtaining sufficient information to identify this constraint requires two witnesses for the Basic HotStuff protocol (Algorithm 2 here). We incorporate a minor change to reduce this to one witness: including the view number of the prepareQC into votes and quorum certificates, denoted as $view_{qc}$. Hence, $view_{qc}$ can be derived from prepareQC# and we only need to check $view_{qc} \le e$, where $e$ is the view number of commitQC1. The chained HotStuff protocol (Algorithm 3 here), for the purpose of maintaining all QCs on the chain, already incorporates such a change.

Forensics for PBFT and VABA

While we only discussed the forensic support for HotStuff, our paper also shows how to obtain it for PBFT and VABA.

Lower Bound on the Forensic Support for Any BFT Protocol

As we observed in the case of HotStuff, when the number of Byzantine replicas are $\geq 2t+1$, we cannot obtain any forensic support. An obvious question is whether this is related to our forensic protocol, or there is a fundamental limit. To address this, we show a lower bound relating the number of Byzantine replicas (denoted $d$) that can be identified by any forensic protocol, the number of faults (denoted $t$) that can be tolerated by the protocol to obtain consensus, and a bound on the actual number of faults (denoted $m$) even when all the transcripts from all replicas (including the Byzantine replicas) are available. We show the following result:

There does not exist a validated Byzantine agreement protocol with weak forensic support with parameters $n$, $t<n/2$, $m \geq n−t$ and $d>n−2t$.

In particular, this implies that the result we obtain is tight. As another special case, when $n = 2t+1$, then all but one replica must go undetected.