Guest post by Joachim Neu, Ertem Nusret Tas, and David Tse

DLS and Nakamoto: Where to Go From Synchrony?

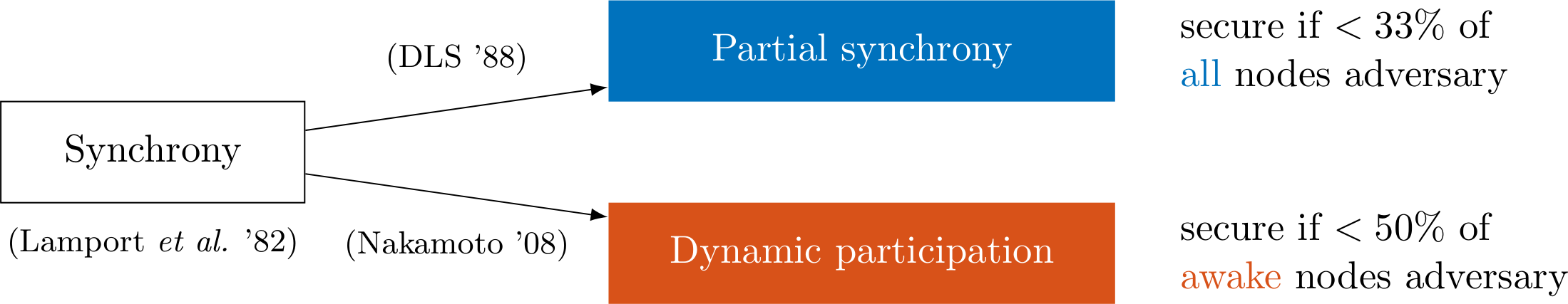

An earlier blog post has explained classical models of the consensus literature from the 1980s, synchrony, asynchrony and partial synchrony. To recapitulate, the most basic network/adversary model is synchrony, where it is assumed that all communication between honest parties suffers a delay that is bounded by a value $\Delta$, known to the protocol. This model was perceived as too simplistic as it does not capture network partitions, i.e., sustained periods of extraordinary delay or even occasional violations of the delay bound. Partial synchrony (introduced by Dwork, Lynch, and Stockmeyer in 1988) extended the synchronous model to be able to capture such periods of asynchrony, using a global stabilization time $\mathsf{GST}$ determined by the adversary and unknown to the protocol. Before $\mathsf{GST}$, the adversary can delay network messages arbitrarily. After $\mathsf{GST}$, delay is bounded again by $\Delta$. Security is guaranteed if less than $33\%$ of the nodes are adversary.

Thirty years later, in 2008, Nakamoto invented the Bitcoin protocol. Equally importantly, the environment the protocol is designed for can be viewed as an extension of the synchrony model in a different direction than partial synchrony. In earlier models it was assumed that honest nodes follow the protocol always. In particular, honest nodes are always awake, they never simply not-participate, for whatever practical impediment such as maintenance or to conserve energy. In contrast, in Nakamoto’s implicit model (later formalized in works such as ‘The Sleepy Model of Consensus’), honest nodes are allowed to fall asleep and wake up, to sometimes not-participate, without being counted as adversarial. The fraction of awake honest parties fluctuates over time, modelling the dynamic participation seen in Internet-scale open-participation consensus infrastructures such as Bitcoin or Ethereum. Security is guaranteed if less than $50\%$ of all awake nodes are adversary, but assuming the asleep nodes are inactive.

A Tale of Two Protocols

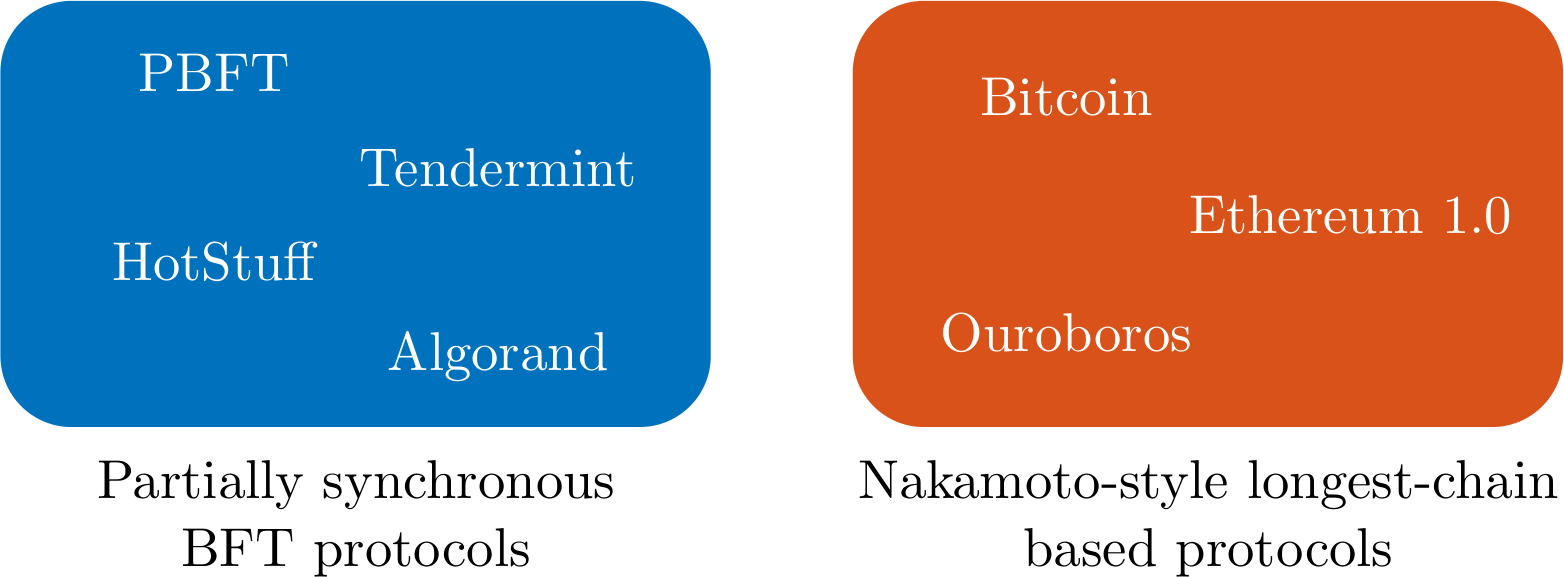

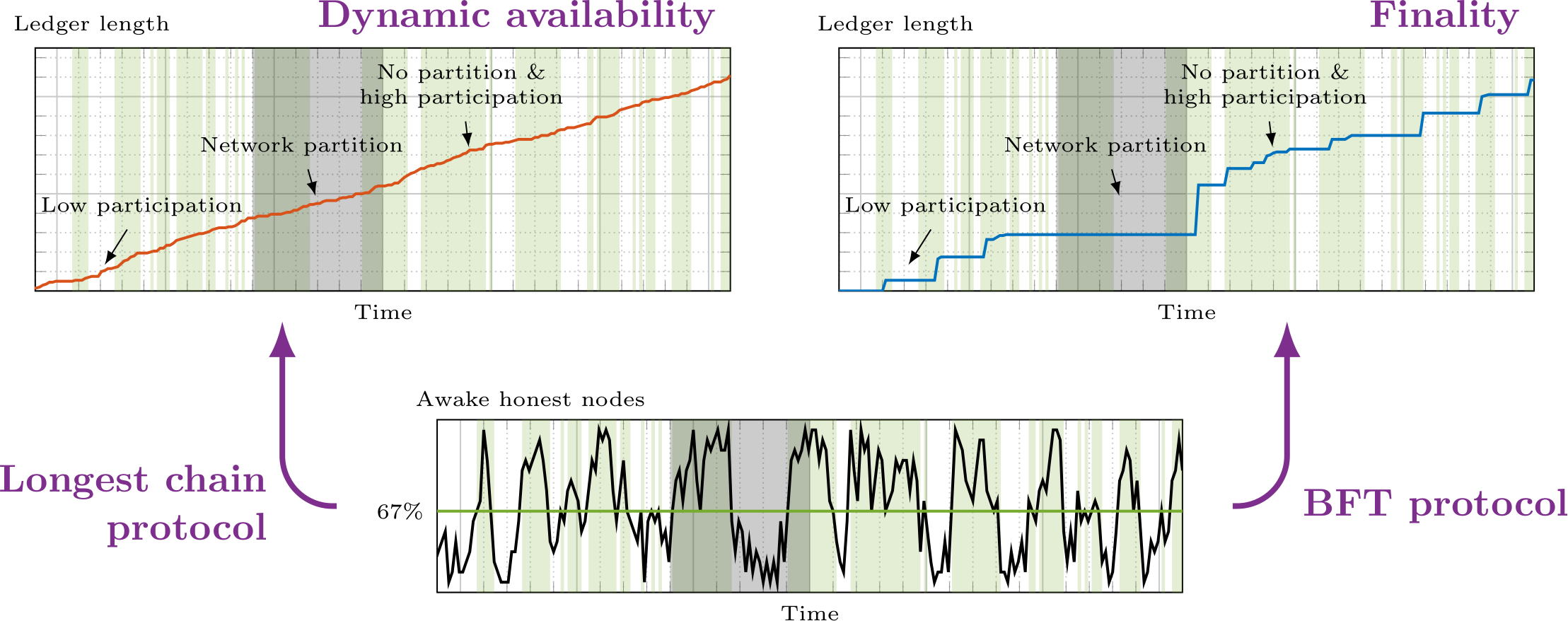

These two incommensurable extensions of the synchronous model have sparked two quite different families of protocols. On the one hand, BFT protocols such as PBFT or HotStuff were designed to operate under partial synchrony. As a result they provide a very strong notion of safety called finality, i.e., a decision once made will under no circumstances be reverted (assuming no more than $33\%$ of the nodes are adversarial). On the other hand, longest-chain based protocols such as Bitcoin or Ouroboros were designed to operate under dynamic participation. They provide enhanced liveness, sometimes called dynamic availability, i.e., they keep making decisions even in periods of low participation.

Which model a protocol was designed for shapes the implicit assumptions it makes and how it interprets the context it is in. As a result, different protocols behave differently when faced with the same scenario, and if a protocol is used in a different model than what it was designed for, then it might make a mistake. Let’s take a closer look at how the model influences the actions of the above two families of protocols.

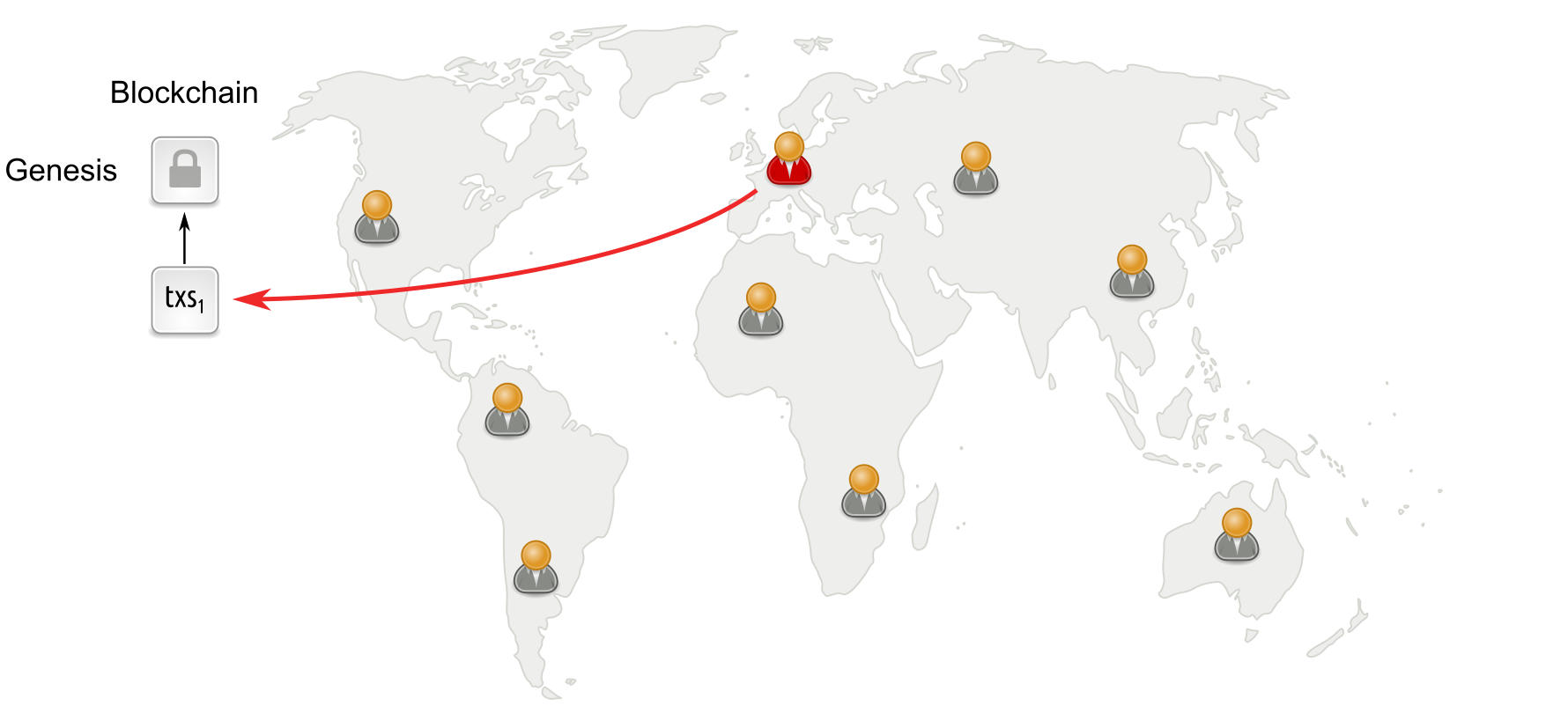

Longest-chain based protocols under normal conditions

In longest-chain based protocols, miners or validators run a lottery (such as trying to solve a proof-of-work or proof-of-stake cryptographic puzzle). The winner gets to append a block with new transactions to the blockchain.

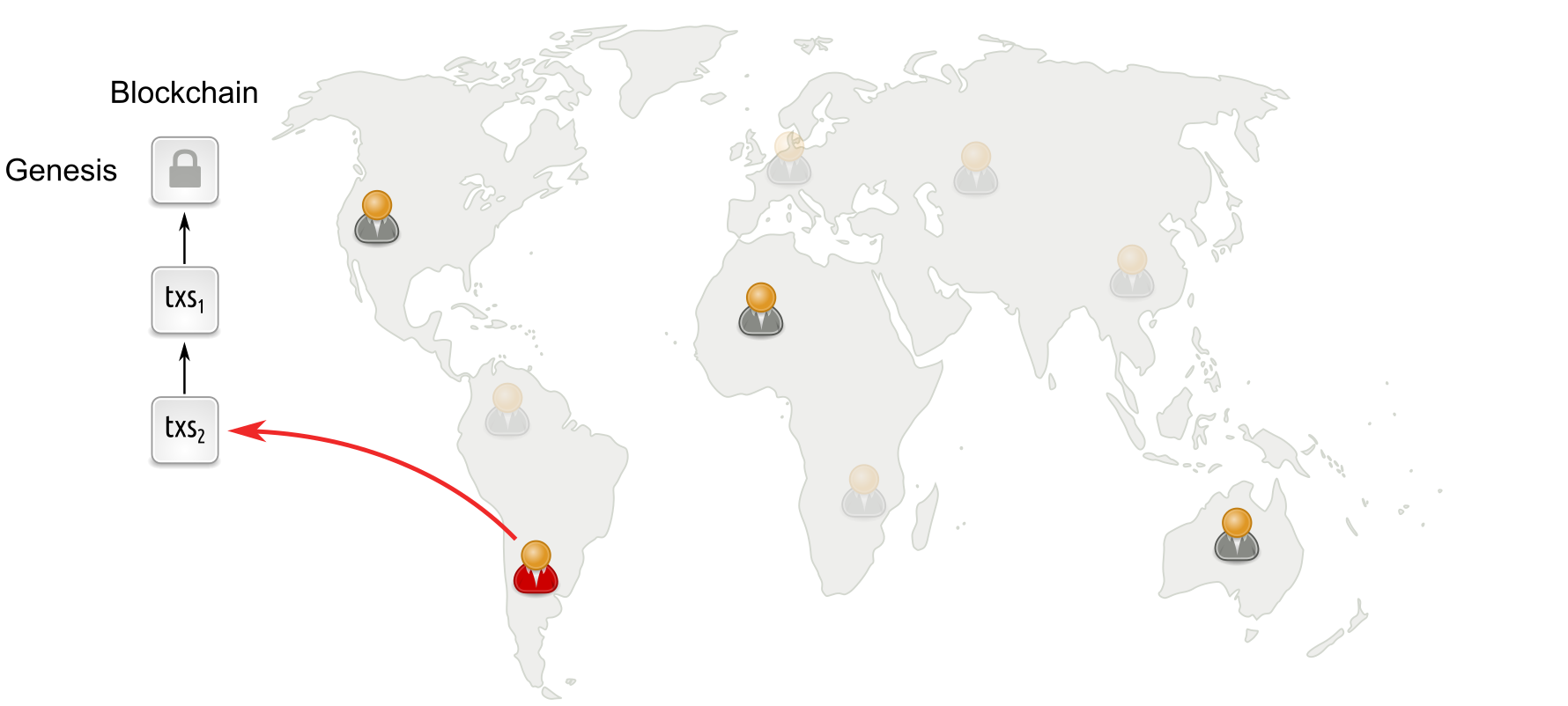

Longest-chain based protocols under low participation

Even if participation is low, the remaining parties keep running the lottery and extending the chain. As a result, the chain always grows and thus the protocol provides dynamic availability.

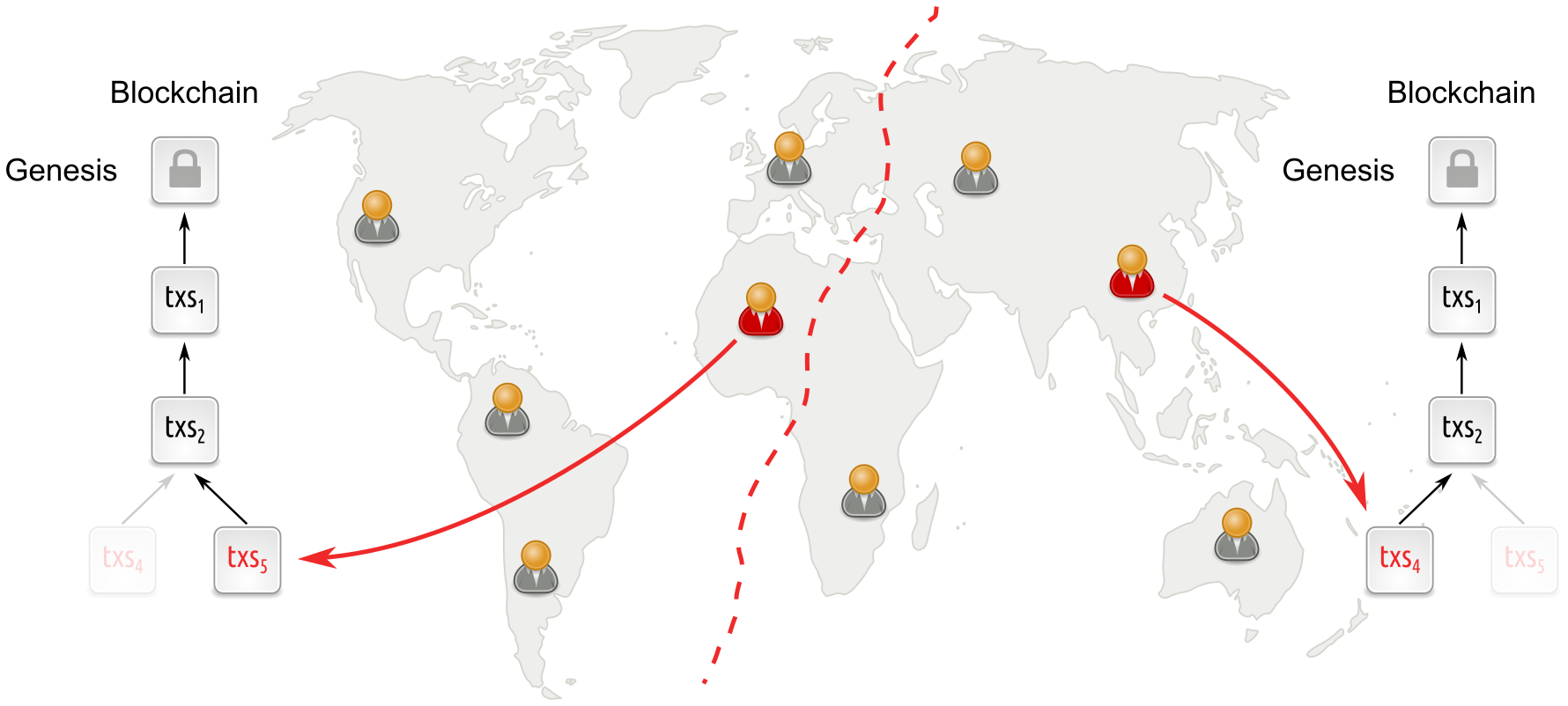

Longest-chain based protocols under network partition

If however there is a network partition, then this will look to participants in individual parts as if participation was low. And since the parties keep going during low participation, separate network parts will continue to build incompatible blockchains. Eventually, when the partition heals, this conflict has to be resolved by reverting all but one chain, resulting in a safety violation. As a result, dynamically available protocols do not provide finality.

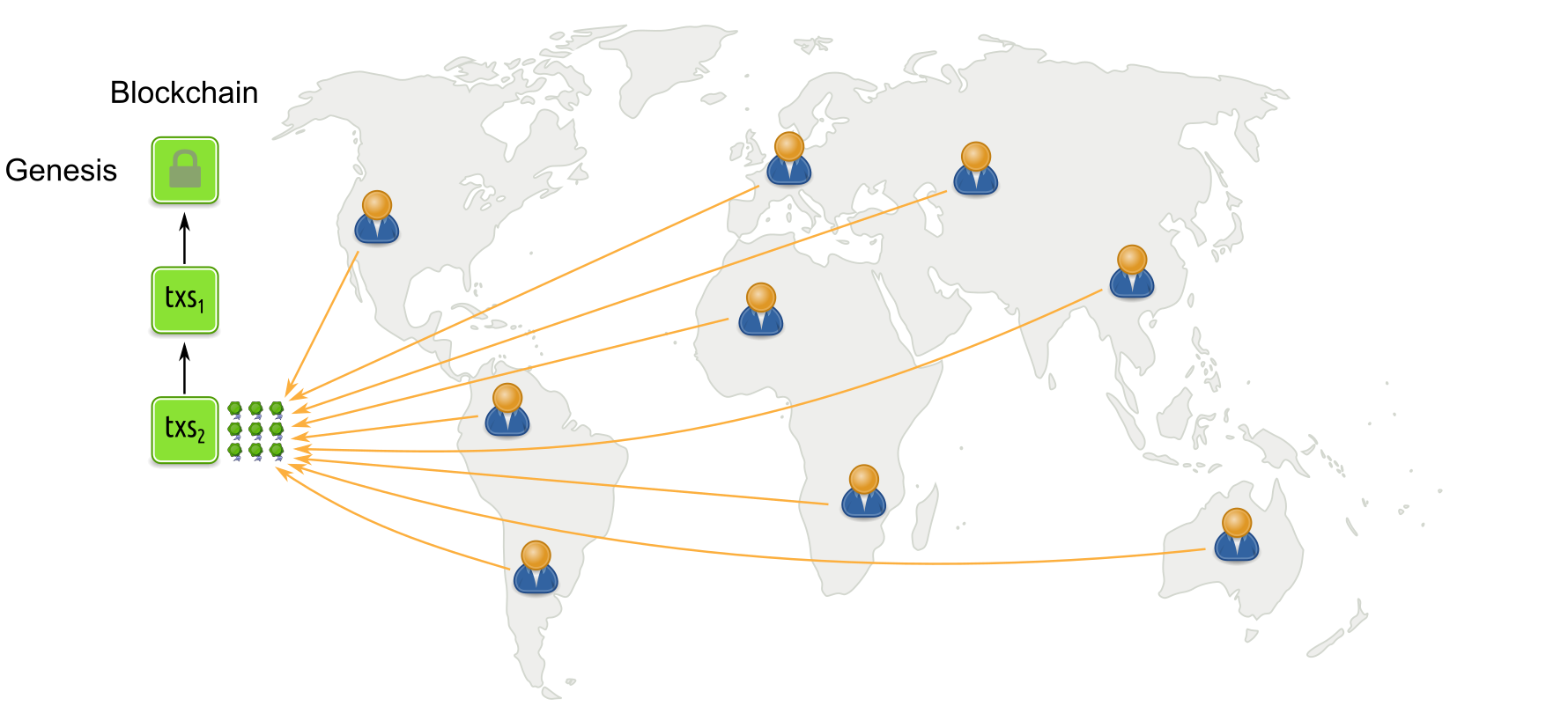

Propose-and-vote style protocols under normal conditions

In propose-and-vote style BFT protocols, all participants are asked to vote for a proposed block. Only if enough votes come together (a quorum), then the block is considered valid and appended to the blockchain.

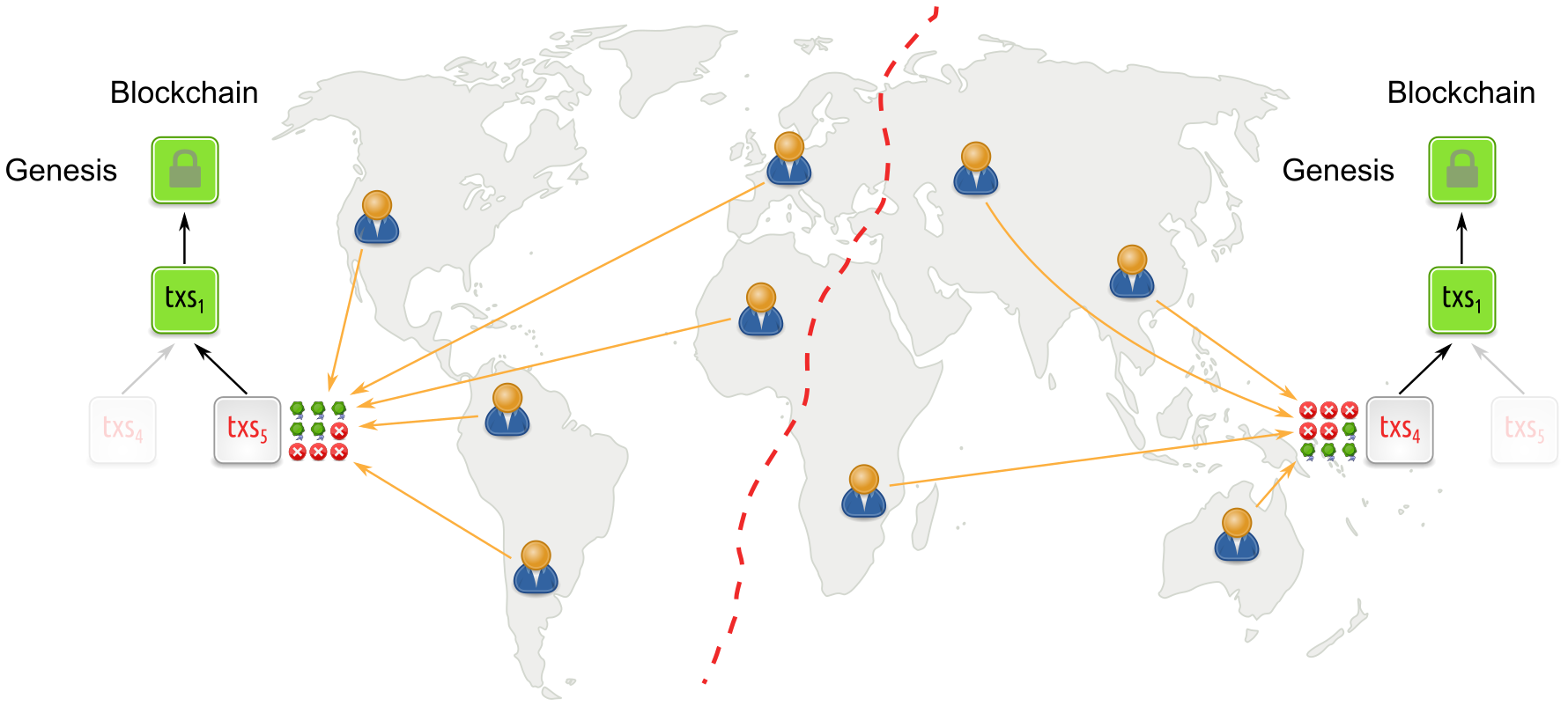

Propose-and-vote style protocols under network partition

As a result, during a network partition, quorum is not reached in the individual parts, preventing the parts from confirming conflicting blocks and obviating reconciliation. BFT protocols thus provide finality.

Propose-and-vote style protocols under low participation

On the flip side, if there is a period of low participation where many participants are asleep, then quorum is not reached as too few votes are being cast. Blocks do not get the votes they need and the blockchain stalls. Thus, BFT protocols do not provide dynamic availability.

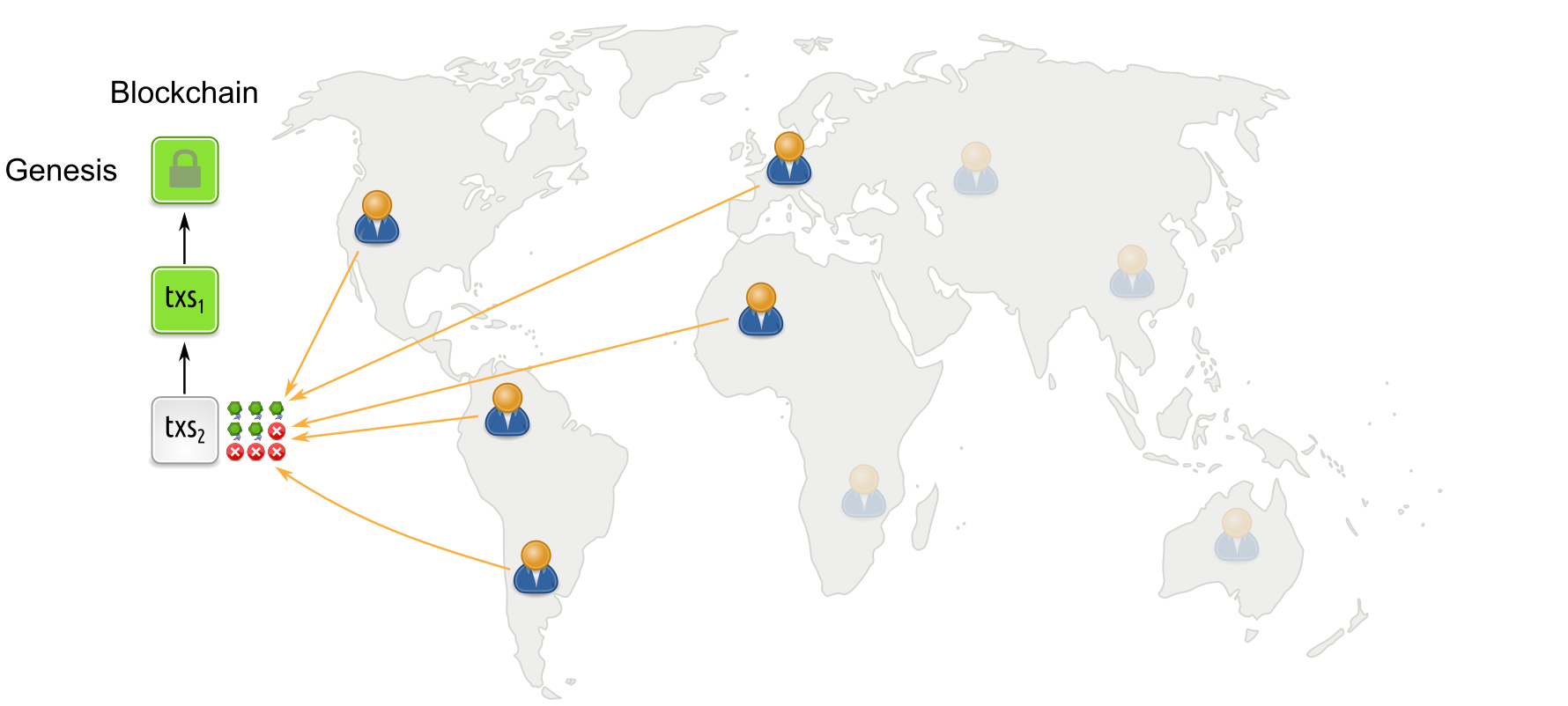

From Protocols to Trust Assumptions

We have witnessed the different behavior of longest chain and BFT protocols under low participation and network partitions. The differences in behavior express different trust assumptions: Participating nodes in longest chain protocols are optimistic: ‘Peers that I don’t hear from are just asleep doing nothing. Thus, it is OK to go ahead without them.’ Participating nodes in BFT protocols are pessimistic: ‘Peers that I don’t hear from are plotting against me! Thus, it is not OK to go ahead without them.’ If we simulate the two protocols under an identical environment with dynamic participation and sporadic network partitions, we see that the ledger output by protocols providing dynamic availability always keeps growing, no matter what, while the ledger output by protocols providing finality stalls during low participation or network partitions.

The Availability-Finality Dilemma

Can we have both? Can we have a consensus protocol that provides both dynamic availability and finality? Obviously not! The ledger from a protocol that provides finality needs to stop growing during network partition, so the protocol cannot be dynamically available. This observation is made formal in a recent variant of the notorious CAP theorem. It is clear that the two families of fundamentally different protocols we have examined before fall exactly on the two different sides of this availability-finality dilemma. Longest chain protocols favor liveness over safety and provide dynamic availability, while BFT protocols favor safety over liveness and provide finality.

The Ebb-and-Flow Property

That’s a bummer. What now? Something in our wishlist needs to be weakened. To look for inspiration, we turn once more to Nakamoto. In Nakamoto consensus, the parameter $k$ of the $k$-deep confirmation rule trades off between confirmation latency and confirmation error probability. Small $k$ means fast latency but high error probability, large $k$ means slow latency but low error probability. You cannot simultaneously have both. Note however that every client can set their own $k$, depending on whether latency or error probability is more important for their application and according to their preferences. And while a client with small $k$ and a client with large $k$ disagree how much of recent history to accept as confirmed, looking far into the past, they share a stabilized common account of history.

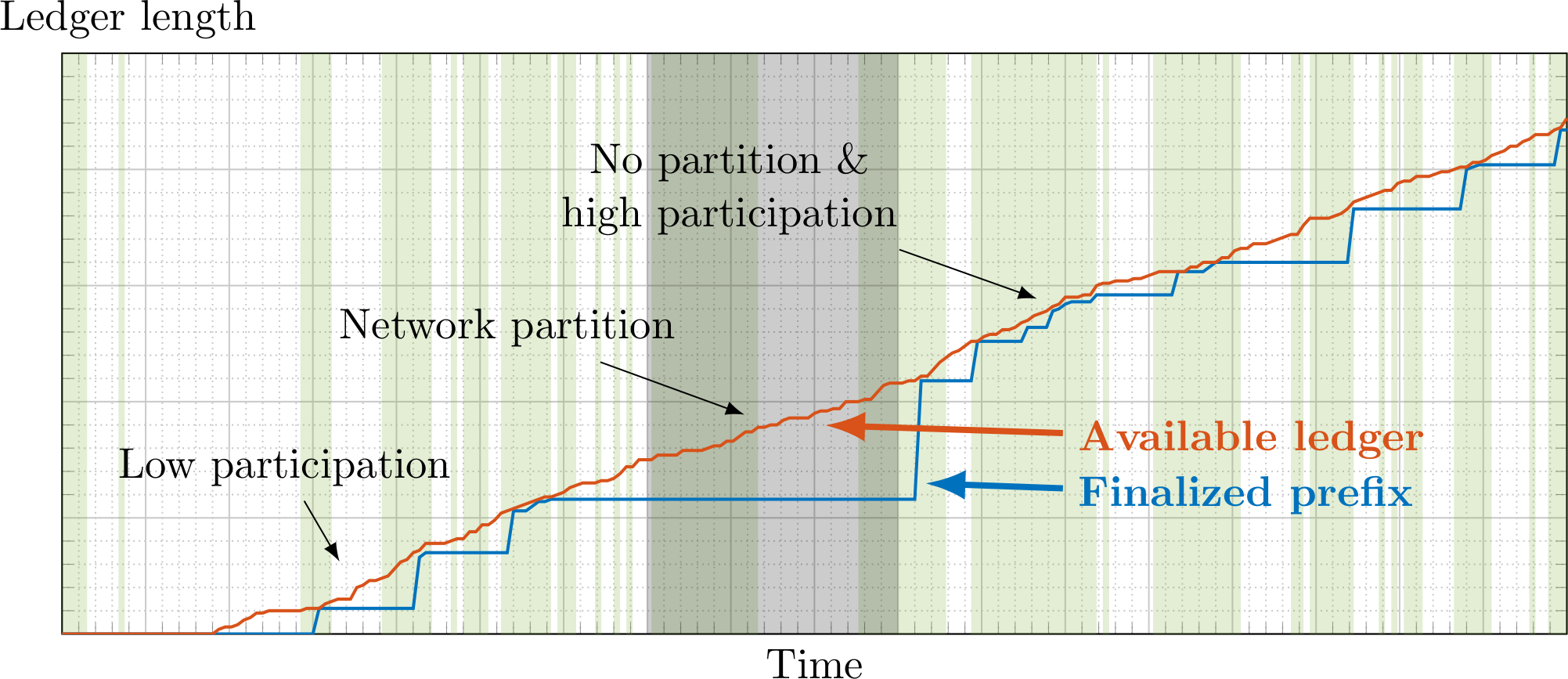

The availability-finality dilemma says that there cannot be a consensus protocol for state-machine replication, one that outputs a single ledger, that provides both properties. The next best thing is then ask for a protocol with two confirmation rules that output two ledgers, one that provides availability under dynamic participation, and one that provides finality even under network partitions, and in the long run they should agree on a common account of history.

The above requirements are made precise by the ebb-and-flow property introduced in this paper. Consider a network environment where:

- Communication is asynchronous until a global stabilization time $\mathsf{GST}$ after which communication becomes synchronous.

- Honest nodes sleep and wake up until a global awake time $\mathsf{GAT}$ after which all nodes are awake. Adversary nodes are always awake.

Then, we say that a protocol $\Pi$ is a $(\beta_1,\beta_2)$-secure ebb-and-flow protocol if it outputs an available ledger $\mathsf{LOG}_{\mathrm{da}}$ and a finalized ledger $\mathsf{LOG}_{\mathrm{fin}}$ satisfying the following properties:

- Finality: The finalized ledger $\mathsf{LOG}_{\mathrm{fin}}$ is guaranteed to be safe at all times, and live after $\max\{\mathsf{GST},\mathsf{GAT}\}$, provided that fewer than $\beta_1$ proportion of all the nodes are adversarial.

- Dynamic Availability: If $\mathsf{GST} = 0$, the available ledger $\mathsf{LOG}_{\mathrm{da}}$ is guaranteed to be safe and live at all times, provided that at all times fewer than $\beta_2$ proportion of the awake nodes are adversarial.

- Prefix: $\mathsf{LOG}_{\mathrm{fin}}$ is a prefix of $\mathsf{LOG}_{\mathrm{da}}$ at all times.

Together, Finality and Dynamic Availability say that the finalized ledger $\mathsf{LOG}_{\mathrm{fin}}$ is safe under network partitions, i.e., before $\max\{\mathsf{GST},\mathsf{GAT}\}$, and afterwards catches up with the available ledger $\mathsf{LOG}_{\mathrm{da}}$. The Prefix property ensures that eventually all clients, no matter what confirmation rule they follow, will still agree on a single account of history.

One motivation for the definition of the ebb-and-flow property was to formalize the design goals implicit in Gasper, the current candidate protocol for Ethereum 2.0’s beacon chain. Upon closer inspection, however, it became apparent that Gasper is not even secure under synchrony but suffers from a liveness attack. So, are there protocols that satisfy the ebb-and-flow property?

The Snap-and-Chat Construction

There are indeed! We next provide a class of protocols, which we call snap-and-chat protocols, that not only provably satisfy the ebb-and-flow security property, but do so with optimal resilience.

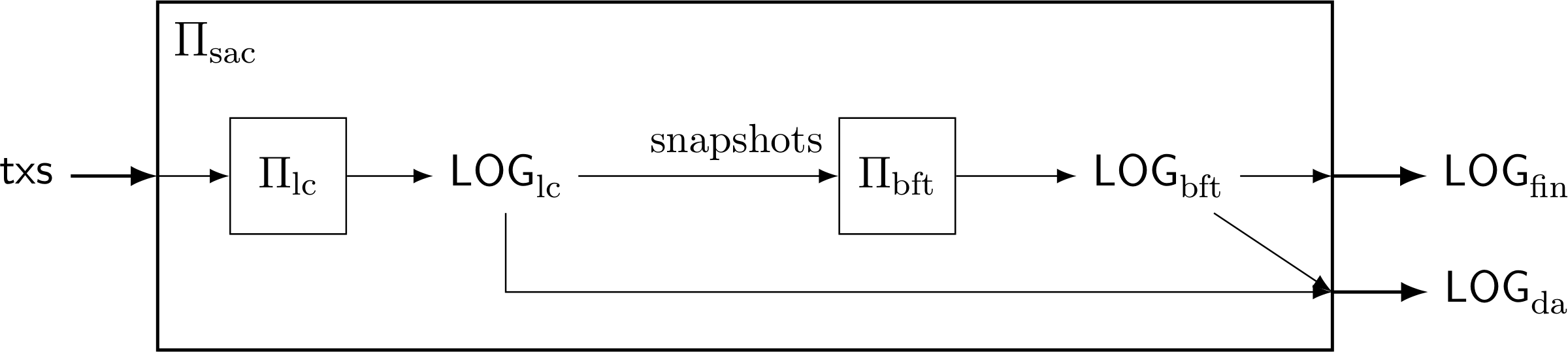

The snap-and-chat construction uses as sub-protocols an off-the-shelf dynamically available protocol $\Pi_{\mathrm{lc}}$, such as a longest-chain protocol, and an off-the-shelf partially synchronous BFT protocol $\Pi_{\mathrm{bft}}$, such as PBFT, Hotstuff, or Streamlet. Nodes execute the snap-and-chat protocol, $\Pi_{\mathrm{sac}}$, by executing the two sub-protocols in parallel. The $\Pi_{\mathrm{lc}}$ sub-protocol takes as inputs transactions $\mathsf{txs}$ from the environment and outputs an ever-increasing ledger $\mathsf{LOG}_{\mathrm{lc}}$. This ledger is generated by whatever confirmation rule native to $\Pi_{\mathrm{lc}}$, such as the $k$-deep confirmation rule if $\Pi_{\mathrm{lc}}$ is a longest-chain protocol. Over time, each node takes snapshots of this ledger based on its own current view, and inputs these snapshots (i.e., whole prefixes of $\mathsf{LOG}_{\mathrm{lc}}$) into the second sub-protocol $\Pi_{\mathrm{bft}}$ for finalization. This can be implemented efficiently, as snapshots can be represented by a reference to the tip of the blockchain that makes $\mathsf{LOG}_{\mathrm{lc}}$. The output ledger $\mathsf{LOG}_{\mathrm{bft}}$ of $\Pi_{\mathrm{bft}}$ is an ordered list of such snapshots. To create the finalized ledger $\mathsf{LOG}_{\mathrm{fin}}$ of transactions, $\mathsf{LOG}_{\mathrm{bft}}$ is flattened (i.e., all snapshots included in $\mathsf{LOG}_{\mathrm{bft}}$ are concatenated) and sanitized so that only the first appearance of a transaction remains. Finally, $\mathsf{LOG}_{\mathrm{lc}}$ is appended to $\mathsf{LOG}_{\mathrm{fin}}$ and sanitized to form the available ledger $\mathsf{LOG}_{\mathrm{da}}$. The append-and-sanitize operation ensures that the transactions in $\mathsf{LOG}_{\mathrm{fin}}$ take precedence over the transactions in $\mathsf{LOG}_{\mathrm{lc}}$ in case there are any conflicts.

Even though honest nodes following a snap-and-chat protocol input snapshots of the (confirmed) ledger $\mathsf{LOG}_{\mathrm{lc}}$ into $\Pi_{\mathrm{bft}}$, an adversary could, in an attempt to break safety, input an ostensible ledger snapshot which really contains unconfirmed transactions. This motivates the last detail of the construction: in the $\Pi_{\mathrm{bft}}$ sub-protocol, each honest node boycotts the finalization of snapshots that are not confirmed in $\Pi_{\mathrm{lc}}$ in its view. An off-the-shelf BFT protocol needs to be modified to implement this constraint. Fortunately, the required modification is minor for several example protocols, including PBFT, Hotstuff and Streamlet.

When any of these slightly modified BFT protocols is used in conjunction with a permissioned longest chain protocol, the resulting snap-and-chat protocol is a secure ebb-and-flow protocol with optimal resilience:

Theorem Snap-and-chat protocols are $(1/3,1/2)$-secure ebb-and-flow protocols.

In what sense does this provide ‘optimal resilience’? If $\mathsf{GAT} = 0$, then the environment is the classical partially synchronous network, and the ledger $\mathsf{LOG}_{\mathrm{fin}}$ has the optimal resilience achievable in that environment ($33\%$). On the other hand, if $\mathsf{GST} = 0$ and $\mathsf{GAT} = \infty$, then the environment is a synchronous network with dynamic participation, and the ledger $\mathsf{LOG}_{\mathrm{da}}$ has the optimal resilience achievable in that environment ($50\%$). Thus, this construction achieves consistency between the two ledgers without sacrificing the best possible security guarantees of the individual ledgers. A resolution of the availability-finality dilemma using a provably secure ebb-and-flow protocol is thus achievable.

Besides optimal resilience, snap-and-chat protocols have other useful properties:

- Snap-and-chat protocols are constructed via an (almost) black-box composition of off-the-shelf protocols. Thus, we can use state-of-the-art dynamically available protocols and state-of-the-art partially synchronous BFT protocols without having to reinvent the wheel.

- As a result, the construction is ‘future-proof’ because it can take advantage of future advances in the design of dynamically available protocols and in the design of partially synchronous BFT protocols. Both problems have received and are continuing to receive significant attention from the community.

- The black-box nature of the composition also enables a relatively easy and modular security proof.

In this paper, we show how to exploit these properties to endow snap-and-chat protocols with additional features such as accountable safety and light-client support.

The BFT sub-protocol in snap-and-chat protocols can be viewed as providing finalized checkpoints for the dynamic ledger. Connections between snap-and-chat protocols and finality gadgets such as Casper FFG are discussed in our papers. Another interesting connection discussed in our paper is with ‘Flexible Byzantine Fault Tolerance’ protocols, which also support multiple ledgers but the consistency requirement between these ledgers is different from that of ebb-and-flow protocols.