This is Part-II of a two-part post on privacy in private proof-of-stake blockchains. In Part-I, we explored attacks on existing private PoS approaches. In this post, we will discuss some ways to obtain privacy (at the expense of safety and/or liveness).

A Three-Way Trade-Off between Safety, Liveness, and Privacy

Madathil et al. had in fact demonstrated that theoretically, a PoS blockchain must forgo privacy to achieve safety and liveness. As a result, designing a practical private PoS requires navigating the trade-offs between privacy, safety, and liveness. In the following, we explore potential solutions that involve trading off one dimension (i.e., safety or liveness) in exchange for privacy guarantees.

Trading-off safety for privacy

Equal weights for every party. To achieve stake privacy, a straightforward method might involve allocating equal weight to every participant in the ledger rather than weighting them based on their stake. This approach would allow each party an equal chance to propose a block or be chosen as a member of the committee that decides the subsequent block. As per this, the stake would function exclusively as an account balance, used only for payment transactions, which can be adequately concealed through cryptographic primitives. However, this approach does not provide any safety against Sybil nodes. As a result, this naive strategy does not work. In essence, this method sacrifices the complete safety assurance in exchange for a strong privacy guarantee for each party’s stake.

Differentially-private stake distortion. On one side, we desire a scenario where the party’s chance of winning the block proposer election isn’t predominantly dependent on their true stake, promoting privacy. However, counterbalancing this, we still aspire to establish a mechanism where the winning odds are proportionate to each party’s stake, guaranteeing safety. A straightforward approach is for each party to employ a distorted stake as the input for running the leader election. Nevertheless, this distortion should concurrently fulfill two conditions:

- The distortion should embody meaningful privacy semantics.

- Distortion of stake could potentially result in an increased adversarial stake. Thus, the mechanism must guarantee a bounded increment in the adversarial stake.

To achieve this, we now present a method that allows for a small, bounded trade-off in safety loss to obtain a reasonably strong and provable privacy guarantee. The general concept involves each party distorting their actual stake with differentially private (DP) noise and using the DP noisy stake for all subsequent ledger election purposes. Hence, the attacker can only infer DP distorted stake values by launching SIA attacks; thus, leaking only distorted stake values provides some privacy guarantees. By default, we add Laplace noises $\sim\mathsf{Lap}(\frac{\alpha}{\epsilon})$, where $\epsilon$ is the privacy parameter (smaller $\epsilon$ means better privacy) and $\alpha > 0$ represents a distinguishing bound (larger $\alpha$ means better privacy). Note that by introducing a distinguishing bound $\alpha$, we permit an attacker to distinguish between a victim’s (unknown) stake $f_v$ and a value $x$ such that that the absolute difference $(f_v - x)$ is greater than $\alpha$.

We stress that the noisy stake is solely employed for ledger maintenance tasks, such as electing leaders and sampling committees. When a party engages in other tasks, such as issuing payment transactions, their true stake is used. Nevertheless, as previously mentioned, cryptographic techniques are sufficient to conceal the stake during payment transactions.

A downside of using distorted stake values for electing leaders and sampling committees is that adversarial stake can be higher than its true value. Consequently, this has a direct effect on the safety properties of the system. In particular, if the distorted stake $\tilde{f}$ is larger than the true stake $f$, then the adversary essentially gains $\tilde{f} - f$. However, since the DP noises are random variables with bounded variances, this ensures that such safety loss is also bounded. Furthermore, by establishing a specific safety objective, such as ensuring the post-distortion stake $\tilde{f}$ remains less than $\frac{1}{3}$, one can obtain a slack $\gamma \in (0,1/3)$, for example, using Chernoff inequalities, such that as long as $f < \frac{1}{3} - \gamma$, there is an overwhelming probability that $\tilde{f}$ will be less than $\frac{1}{3}$.

Additionally, this design offers flexibility in selecting the desired privacy level. For example, one could choose DP noises with a smaller variance (resulting in weaker privacy in DP) to maintain a smaller $\alpha$ (a better safety guarantee), and vice versa.

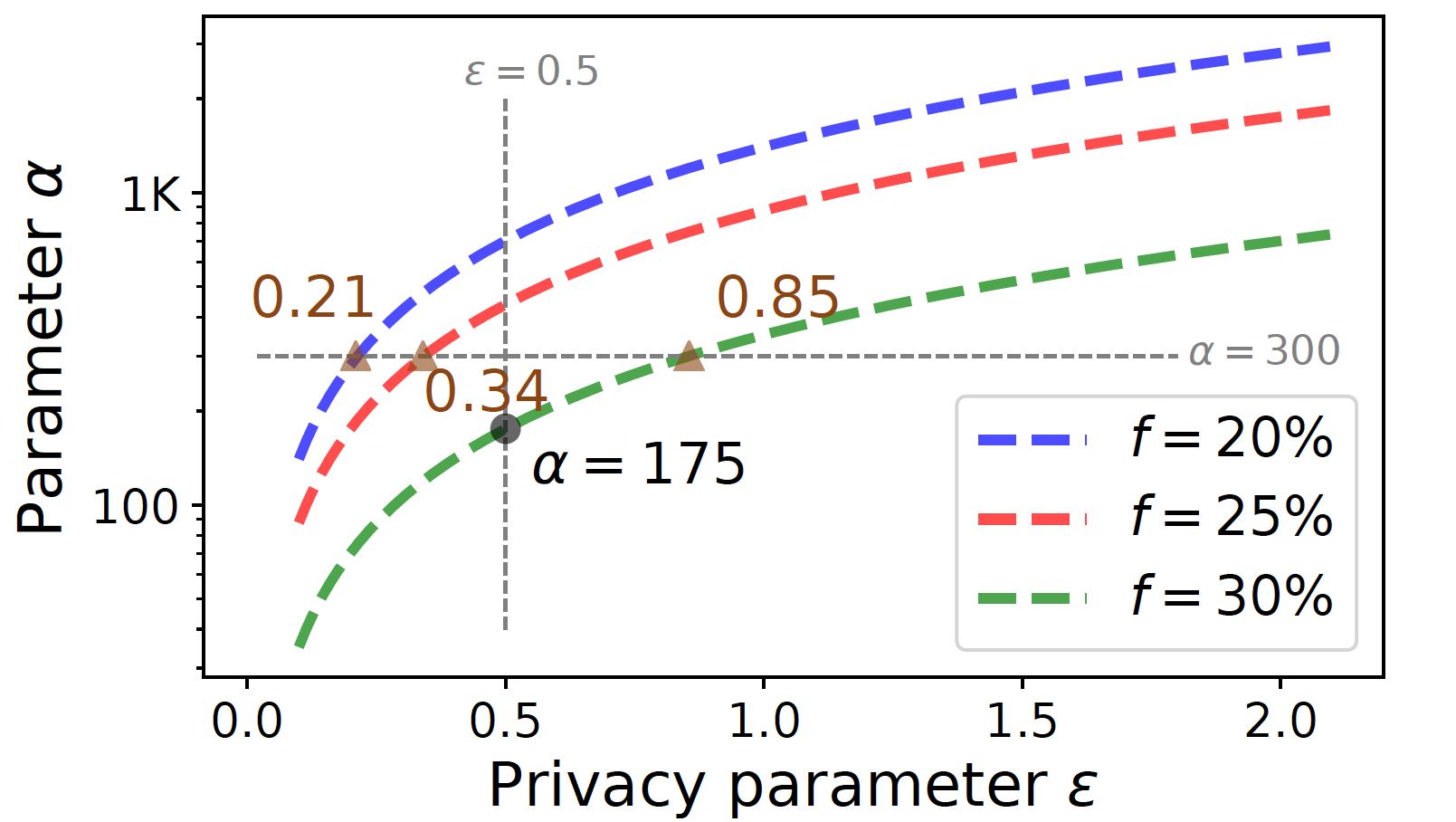

A case study on DP stake distortion. We now present a case study to better understand the safety-privacy trade-off obtained when using our stake distortion protocol on Ethereum 2.0. Specifically, we first plot privacy-safety curves in the following figure showing the best privacy (under the requirement of post-distortion adversarial stake to be smaller than $\frac{1}{3}$) attainable at a specified safety level (malicious tolerance).

The tradeoff is pretty evident from the figure above; for instance, one can achieve better privacy with a larger $\alpha$ or a smaller $\epsilon$ when considering a relatively weaker safety (smaller malicious tolerance). Moreover, this property also provides flexibility to practitioners in fine-tuning the protocols. For instance, if a slashing mechanism is in place to minimize the malicious fraction, one might opt for better privacy by choosing a weaker safety.

Next, we run stake distortion simulations to validate the privacy-safety curves. Specifically, we emulate the Ethereum 2.0 leader election protocol and adjust distortion parameters according to the privacy-safety curves. Following this, we perform simulated stake distortion over 10K rounds, aiming to identify any potential safety violations, i.e., if the post-distortion adversarial stake exceeds $\frac{1}{3}$. We sumarize the results in the following table

| Pre-distortion ACS | $(\epsilon, \alpha)$ | Max Post-distortion ACS |

|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | (0.5, 1214) | 0.33082 |

| 0.15 | (0.5, 963) | 0.32952 |

| 0.2 | (0.5, 701) | 0.33055 |

| 0.25 | (0.5, 438) | 0.32858 |

| 0.3 | (0.5, 175) | 0.32309 |

AS: Adversial controlled stake

The table indicates that, even under 10K stake distortions, not a single safety violation arises.

Discussion

In the previous section, we’ve explored potential solutions that trade-off safety for privacy without affecting liveness. It raises an intriguing question:

Can we trade off liveness for the sake of privacy?

While we have not argued these solutions formally in our work, we will share a few ideas that could be extended to effective solutions.

Disable chain growth. The basic premise of a stake inference attack involves an attacker observing whether their self-created transaction is confirmed on time. A direct countermeasure to mitigate SIA would be to halt chain growth, effectively eliminating the attacker’s ability to carry out SIA. While this approach ensures perfect privacy, it comes at the cost of completely sacrificing liveness.

Random delay for transaction proposal. We now propose a proof-of-concept mitigation strategy that incorporates random delays for the proposal of submitted transactions. In essence, when a leader is elected, they flip a biased coin for each received transaction and only include the transaction in the proposed block if the coin lands on heads. This process introduces uncertainty regarding the timing of transaction confirmations, making it difficult for attackers to execute SIA attacks. On the downside, this method can result in some transactions being delayed, indicating a trade-off in liveness. However, by adjusting the bias of the coin being flipped, one can control the extent of the liveness loss.

Acknowledgment. We would like to thank Ittai Abraham and Ashwin Machanavajjhala for their feedback on this post.

Please post your comments on Twitter.