In this post, we will present (a variant of) PBFT, which is the first practical solution to Byzantine fault tolerant state machine replication under partial synchrony. The protocol follows the key ideas presented in the previous post on partial synchrony.

Setting

There are $n$ parties, at most $t<n/3$ of them can have Byzantine failures. The network is partially synchronous, so messages after GST arrive after at most $\Delta$ delay. We assume a PKI setup where each server knows the public keys of all other servers and public keys of the clients.

Parties receive requests from clients over time. There is an agreed-upon external validity function that defines what are valid requests.

Data structure

Each party maintains a chain of blocks, where each block contains a batch of client requests and a pointer to a previous block. The chain starts from an empty genesis block denoted $B_0$. We say that a block has height $k$ if it is $k$ hops on the chain from the genesis. A block $B_k$ at height $k$ has the following format $B_k := (b_k, h_{k-1})$

where $b_k$ denotes a batch of client requests and $h_{k-1} := H(b_{k-1})$ is a hash digest of the predecessor block. The first block $B_0=(\bot, \bot)$ has no predecessor. Every subsequent block $B_k$ must specify a predecessor block $B_{k-1}$ by including a hash of it.

For a block $B_k$ let $chain(B_k)$ be the sequence of blocks $B_0,B_1,\dots, B_k$. We say $B_l$ extends $B_k$, if $chain(B_k)$ is strict sub-chain of $chain(B_l)$. Note that in such a case it must be that $l>k$. We say two blocks equivocate one another if they are not equal and no one of them extends the other one.

Certificates

Certificate: Let $C_v(B_{k})$ denote a set of vote signatures on $B_{k}$ by $n-t$ parties in view $v$. We call $C_v(B_{k})$ a certificate for $B_{k}$ from view $v$. Certified blocks are ranked by the views in which they are certified, i.e., a certificate $C_v(B_k)$ is ranked higher than $C_{v’}(B_{k’}’)$ if $v > v’$. Looking ahead, every party maintains the highest ranked certificate as its lock.

Commit Certificate: Let $CC_{v}(B_{k})$ denote a set of vote2 signatures on $B_{k}$ by $n-t$ parties in view $v$. We call $CC_{v}(B_{k})$ a commit certificate for $chain(B_{k})$ from view $v$.

Properties of PBFT

- Safety: For any two valid commit certificates $CC_{v}(B_{k})$ and $CC_{v’}(B_{k’}’)$, either $B_k=B_{k’}’$ or $B_{k}$ extends $B_{k’}’$ or $B_{k’}’$ extends $B_k$. In other words: $B_k$ and $B_{k’}’$ do not equivocate.

- Liveness: If a client sends a valid request $txn$, then each non-faulty party will eventually know of some commit certificate $CC_{v}(B_{k})$ such that exists $B_{k’} \in chain(B_k)$ and $txn \in B_{k’}$.

- External Validity: If there is a commit certificate $CC_{v}(B_{k})$ then each request in each block of $chain(B_k)$ can be uniquely mapped to a valid client request.

Note that this is a modern view that focuses on publicly verifiable certificates.

Protocol description

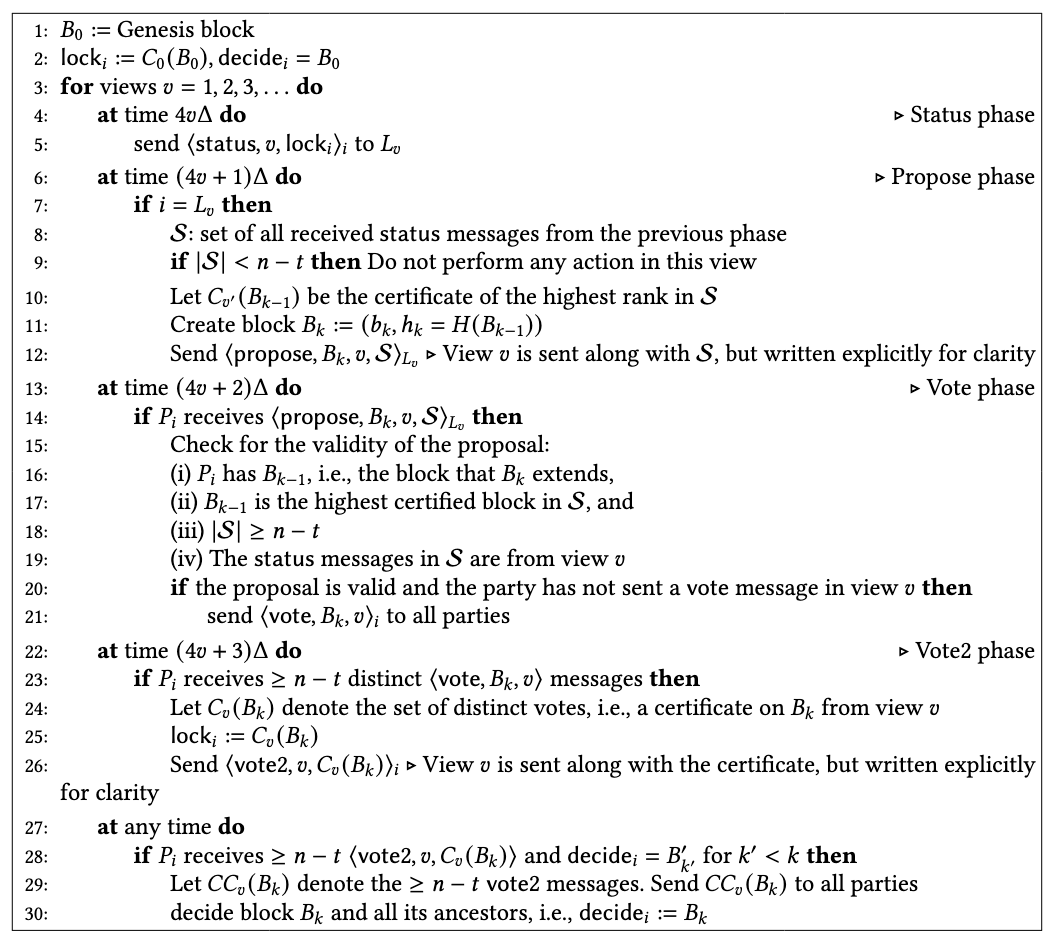

To simplify exposition, we assume all parties have synchronized clocks. The protocol works in views (iterations), where view $v$ starts at time $4\Delta v$. Each view proceeds in four different phases: Status, Propose, Vote, Vote2 that are staggered $\Delta$ time apart. In each view $v$, we assume there is a designated leader that is deterministically known based on the party’s identity and the view number, e.g., the leader is $v \mod n$. The protocol is described in the figure below.

Walkthrough

Let us walk through the protocol to understand the steps:

-

Initially, all parties are locked on the genesis block $B_0$. They send $C_0(B_0)$ to the leader $L_1$ as their lock.

-

In the propose phase, the leader tallies whether it has received $n-t$ locks in the status phase of the view (this is guaranteed to happen after GST). If so, then the leader creates a block extending the lock of the highest rank. In this case, it will create $B_1$ extending $B_0$, and propose it to all parties.

-

The proposal for a view $v$ contains a set $S$ of $n-t$ status messages for view $v$, where each such message contains a lock. On receiving a proposal, each party checks for the validity of the proposal, namely, whether $B_k$ extends a block of height $k-1$, it already has received block $B_{k-1}$, and whether the status messages $S$ for view $v$, have sufficiently many valid locks. If all of these checks pass, it multicasts a vote for the block and also updates its lock to the highest certified block in $S$.

-

In the next phase, if $P_i$ receives $\geq n-t$ (first round of) votes for the block in this view, it creates a certificate for this block, and locks on this block. The party then multicasts a second vote (vote2) for $B_k$. At anytime, if it receives $\geq n-t$ second round of votes on the block, it decides on this block and all its ancestors. It also forwards the $\geq n-t$ vote2 messages which is a commit certificate to all parties.

-

The ideas presented here follow the blueprint from the previous post:

- The first round of votes (Vote phase) ensures non-equivocation by a leader. In particular, if a party has a certificate $C_v(B_k)$ for some block $B_k$ from view $v$, an equivocating certificate cannot exist in view $v$.

- The second round of votes (Vote2 phase) is the phase in which parties lock. If a party thus obtains $n-t$ vote2 messages and commits on a block $B_k$, it ensures that $\geq n-t$ parties and thus $\geq n-2t$ honest parties are locked on $B_k$.

- The status phase ensures that the next leader learns about this lock if the leader receives $n-t$ status messages and if any honest party has indeed committed. This is because $\geq n-2t$ honest parties will intersect with the $\geq n-t$ status messages that the leader receives. Observe that if no party committed, then from a safety standpoint, it does not matter whether the next leader received the lock. Moreover, if an honest leader receives $< n-t$ status messages, which can happen before GST, it will not propose.

- Finally, sending the status certificate $S$ of $\geq n-t$ locks from the parties ensures that every party can verify that a Byzantine leader has not incorrectly extended the wrong lock. Every party can essentially validate the leader’s task in lines 15-19.

Moreover, if a view starts well after GST, and if the leader is honest, observe that a block is guaranteed to be proposed, voted, and committed by all honest parties. This process guarantees liveness of the protocol.

Proof of Safety

Lemma 1. If there exist $v \le v’$ with a commit certificate $CC_v(B_k)$ from view $v$ and a lock certificate $C_{v’}(B_{k’}’)$ from view $v’$, then $chain(B_k)$ is a prefix of $chain(B_{k’}’)$.

Proof. We will use induction on $v’$.

Base case. $v’ = v$, i.e., $B_{k’}’$ was certified in view $v$. In this case it must be that $B_{k’}’=B_k$ because otherwise, both $B_{k}$ and $B_{k’}’$ got $\geq n-t$ votes. Since $n-2t>t$ means that at least one honest party had to vote for $B_{k}$ and $B_{k’}’$ but this is a contradiction to line 20.

Since $CC_v(B_k)$ exists, consider the at least $n-2t$ honest parties that sent a vote2 message. Call this set $H$. Clearly the size of $H$ is at least $t+1$ and at the end of view $v$, each party in $H$ has $lock:=C_v(B_k)$.

Induction step. We will prove three things:

- Any valid status messages that has a $C_v(B_{k’}’)$ of rank $v\le u<v’$, must have $chain(B_k) \subset chain(B_{k’}’)$. This follows from the induction hypothesis.

- Any set of $n-t$ valid status messages for view $v’$ must include at least one member of $H$. This follows from quorum intersection between the status certificate and $H$.

- Any member of $H$ that sends a status message for view $v’$ will have lock whose rank is at least $v$ and whose chain includes $chain(B_k)$ as a prefix. This again follows from the induction hypothesis.

Taken together, we have proven that any set of $n-t$ valid status messages must include at least one lock from view at least $v$ that includes $chain(B_k)$ as a prefix. Moreover, the highest ranked lock in this set must either be this lock or a lock with a higher rank that still includes $chain(B_k)$ as a prefix.

Thus, for a leader of view $v’$ to create a valid block with a valid $S$ such that an honest party votes for it, it must create a block that extends $B_k$.

Theorem 1. For each height $l$, if two honest parties commit $B_l$ and $B’_l$, then $B_l = B_l’$.

Proof. Suppose for contradiction, this is not true. Let them be committed as a result of committing blocks $B_k$ and $B_{k’}’$ in views $v$ and $v’$ respectively. Thus, $B_l$ is or extends $B_k$ and $B_{k’}’$ is or extends $B_l’$.

WLOG, suppose $v’ \geq v$. If $v’ = v$, then suppose $k’ \geq k$. By Lemma 1, $C_{v’}(B_{k’}’)$ must equal or extend $B_k$. Thus, $B_l = B_{l’}$.

Proof of liveness

Lemma 2. Assuming view $v$ started at time $\geq GST + \Delta$ and the leader of view $v$ is honest, then honest parties will commit a block in view $v$.

Proof. Seeking a contradiction, assume that a non-faulty client sends a transaction to all parties at time 0, but no honest party knows a new commit-certificate by the end of $\text{GST}+4\Delta (t+2)$ that includes this transaction.

Let $v$ be the first view with an honest leader that starts after $\text{GST}+\Delta$. This must happen at time $T$ and $T < \text{GST}+4\Delta (t+1)$.

Before time $T+\Delta$ time, the primary of view $v$ will receive $n-t$ valid status messages for view $v$. Hence the primary will send a propose message and before time $T+2\Delta$ all honest parties will see this is a valid proposal and send a vote message. So before time $T+3\Delta$, all honest parties will see $n-t$ vote messages and send a vote2 message. So before time $T+4\Delta$ which is less than $\text{GST}+4\Delta (t+2)$, all parties will get a commit certificate.

This is a contradiction.

Message complexity

The good news is that in each view, the number of messages is $O(n^2)$. The bad news is that, naively, the size of some messages is large. In particular, certificates require $n-t$ signatures, and proposal messages send a status with $n-t$ certificates.

So the naive complexity after GST is $O(n)$ views, each with $O(n^3)$ words (where each word can contain $O(1)$ signatures) being sent for a total of $O(n^4)$ words.

Certificates can be compressed via threshold signatures or in practice via multi-signatures to a constant number of words.

Notes

How does the protocol here compare with the original PBFT paper? The above description captures the essence of PBFT. However, since we are looking at this protocol in the era of blockchain 25 years from when PBFT was proposed, we explain it differently even though the core ideas are the same. Here are some differences:

- Chaining. The above description assumes that blocks are chained and deciding a block decides all its predecessors. The original protocol attempted to achieve consensus separately for each slot.

- Steady state and view change. In our description, in each view, we propose a block and then perform a view change. The original description worked in a “steady state and view change” model, where there is a designated leader who can achieve consensus on several blocks in a view. The leaders change, and thus a view change happens, only if sufficiently many honest parties believe that the leader is not doing its job. Thus, the parties engage in a blame mechanism before changing views.

- Synchronizing views to wall-clock time. As a simplification, the above description assumes that all parties and their wall-clocks are perfectly synchronized. Moreover, parties run views and different rounds within the view at fixed known times. This provides simplicity but the latency of the protocol is inherently dependent on $\Delta$. The original description provided an optimistically responsive protocol where under good conditions, parties can decide values at the speed of the network.

- Garbage collection. For simplicity, we assume the parties maintain the entire chain in their storage forever. The original description presented a garbage collection routine to ensure the storage does not grow indefinitely.

Leader election. In the above description, we assume that the leaders for each view are known to all parties. In practice, this needs to be replaced by some means to elect these leaders.

Modular description in a prior post. A longer and more modular way to understand PBFT (and its variants like HotStuff) is first to understand Paxos from recoverable broadcast, then provable broadcast, and finally PBFT from provable broadcast.

We thank Nibesh Shrestha and Samuel Laferriere for helpful feedback on this post.

Please leave comments on X.