Achieving high throughput is essential for blockchain ecosystems to become competitive alternatives to their centralized counterparts across a wide range of domains. For example, high-frequency trading on decentralized platforms cannot be competitive unless transaction processing times are reduced to well below one second. The predominant strategy to address this challenge has been the development of Layer 2 (L2) scaling solutions. However, this approach often introduces trade-offs, potentially compromising decentralization and, consequently, the core value proposition of blockchain technology. This reality underscores the importance of scaling the Layer 1 (L1) protocol directly. But to what extent is this possible?

As we push L1s into fast-block regimes, new challenges arise. One challenge is that, in the presence of transmission latency, strategic behavior by miners can create a bottleneck. This post provides a game-theoretical analysis of the impact of block propagation latency on the supply of block capacity in Nakamoto consensus, based on the paper Latency Trade-offs in Blockchain Capacity Management by Michele Fabi (2025). The framework outlined here is most relevant when target block times are on the order of seconds or milliseconds, making propagation latency quantitatively significant.

The Latency-Revenue Trade-off

At the heart of the analysis that follows is a trade-off faced by blockchain miners in a fast-block environment:

-

Proposing Large Blocks for More Fees: On one hand, miners are incentivized to create large blocks. A larger block can accommodate more transactions, and each transaction carries a fee. By maximizing the data included in a block, a miner maximizes their potential fee revenue.

-

Proposing Smaller Blocks for Speedier Propagation: On the other hand, the downside to size is higher latency. A larger block, containing more data, takes longer to propagate across the miner network. During this propagation time, another miner might produce and broadcast a competing block. If this competing block is smaller and thus propagates faster, it may reach a majority of the network first. In this scenario, the larger, slower block is tail-gated and thus “orphaned” by the network. Its miner loses out on both the transaction fees and the fixed block reward (the coinbase).

This creates the central conflict of the paper: Should a miner propose a large, more profitable block that risks being orphaned, or a smaller, faster block that has a higher chance of being accepted but yields lower fee revenue?

Crucially, the optimal decision for one miner depends on the strategies of all other miners. If others are proposing large, slow blocks, a miner might gain an edge by proposing a smaller one. If everyone else is proposing small blocks, there might be an opportunity to capture more fees with a larger one. This interdependence makes the choice of block size a game theory problem, which we will now formalize.

Setting the Stage

Ren’s work on the Security Proof for Nakamoto Consensus (2019 blog post here) introduces a Poisson process for block arrivals assuming a synchronous network with bounded delay Δ.

Building directly on this setting, we model individual miner incentives: miners now choose the capacity (i.e., the size) of their blocks strategically, which we denote by $k$. All the original assumptions remain identical, except that blocks now face a propagation delay that scales linearly with their size. Hence, blocks face a delay of Δk units of time.

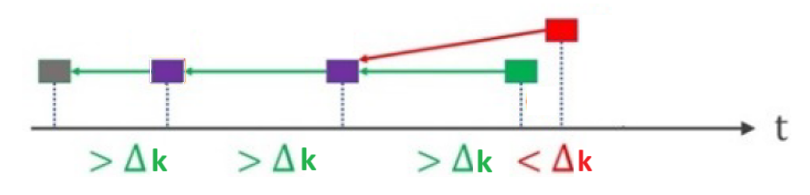

The timeline below illustrates how honest blocks that are mined too close in time (< Δk) may fork or tailgate one another.

Notation Table

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| $Δ$ | Propagation delay per kB |

| $μ$ | Block production rate |

| $α$ | Transaction‑data inflow |

| $τ$ | Fee per kB |

| $π$ | Coinbase reward (fixed) |

| $k$ | Block capacity |

| $λ$ | Growth rate of the honest chain |

| $ρ$ | System load $=α/λk$ |

| $Ac$ | Adversary cost per second |

1. Latency and Strategic Block Capacity

In each mining round (starting when a new block is added to the honest chain), miner $m$ selects a block capacity $k_m \in \mathbb{R}_{+}$ for the next proposed block.

We make the following assumptions on the two opposing forces that shape this choice:

- Fee revenue. Transaction fees are earned at a marginal rate $\tau$ per kB of data, so expected gross revenue, $\tau k_m$, increases linearly with block size.

- Latency risk. Block propagation time increases linearly in size, $\Delta k_m$; a larger block takes longer to reach the network, raising the chance that it is overtaken and orphaned by a faster competitor.

Importantly, the probability that miner $m$’s block is accepted depends not only on its own capacity choice but also on those chosen by all other miners. Let $k_{-m} = (k_{1}, …, k_{m-1}, k_{m+1}, …, k_{M})$ denote the vector of competing capacities. The win probability is given by

\[P_m(k_m; k_{-m}) = \Pr[ T_m + \Delta k_m < \min_{j \neq m} \{ T_j + \Delta k_j \} ],\]where $T_j \sim \text{Exp}(\mu/M)$ are independent exponential random variables representing Poisson block arrival times, and $\mu$ is the aggregate block production rate.

The expected payoff for miner $m$ is

\[R_m(k_m; k_{-m}) = P_m(k_m; k_{-m}) \cdot (\pi + \tau k_m),\]with $\pi$ denoting the fixed coinbase reward. A miner’s best response to the capacity profile of others is

\[k_m^{\star} = \arg\max_{k_m \geq 0} R_m(k_m; \mathbf{k}_{-m})\]This interdependence makes the capacity choice a fully strategic decision: each miner’s optimal block size depends on beliefs about the sizes chosen by others.

2. Equilibrium Block Capacity

Neglecting block size limits imposed by the protocol (see discussion below), each miner’s chosen capacity cannot exceed the current mempool size $Q$ nor fall below zero. When these bounds are not binding, the block capacity that arises in the unique symmetric Nash equilibrium of the game is

\[k_m^{\mathrm{NE}}(\pi,\tau,\mu)=\frac{\mu_{-m}^{-1}}{\Delta}-\frac{\pi}{\tau}.\]Here

\[\mu_{-m}=\mu \frac{M-1}{M}\]is the aggregate block‑production rate of the other miners (assuming homogeneous hash rates). The term $\mu_{-m}^{-1}/\Delta$ captures the ratio of their expected inter‑block time to the per‑unit propagation delay, while $\pi/τ$ expresses the relative weight of the size‑independent coinbase reward.

We can see that:

- Small Δ relative to $\mu_{-m}^{-1}$ ⇒ larger blocks.

- Large $\pi/\tau$ ⇒ smaller blocks.

- As $M\to\infty$, $\mu_{-m}\to\mu$.

The effects of these ratios on the equilibrium block size are intuitive: if the transmission delay is short relative to the block production time, then the increase in forking risk caused by recording more transactions becomes less of a concern, thus miners increase block capacity.

On the other hand, since fees rise from recording more transactions but the coinbase does not, a larger coinbase lowers miners’ incentive to add transactions. Extra transactions prolong propagation and raise orphan risk, so a higher coinbase shifts the cost‑benefit cutoff to a lower equilibrium capacity.

When the mining population is large ($M\to\infty$), $\mu_{-m}$ converges to the aggregate block‑production rate $\mu$.

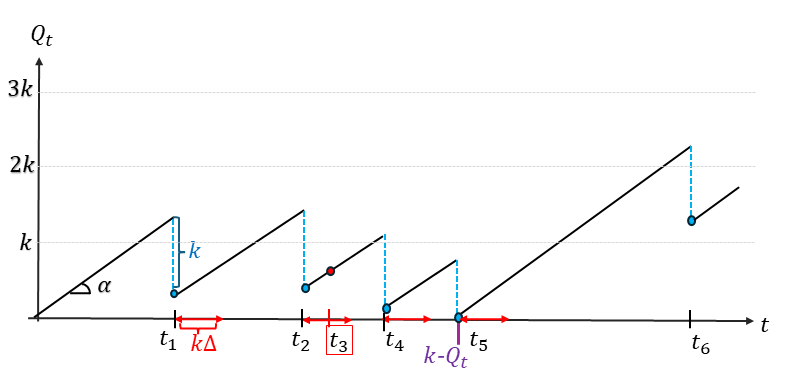

3. Mempool Dynamics

To connect miner incentives with user latency, we model the mempool as a continuous bulk‑service queue: transactions flow in at a rate of α, while blocks of size k—strategically chosen by miners—clear this data in batches. This extends the discrete M/M[K]/1 framework of Huberman‑Leshno‑Moallemi (2019) and the binary‑block M/M/1 queues of Hinzen et al. (2019) and Easley et al. (2019). Similar stochastic processes are also found in inventory theory and in neuroscience for modeling integrate-and-fire neurons.

The mempool size $Q_t$ follows the stochastic differential equation:

\[d Q_t = \alpha dt - \min ( k,Q_t ) d B_t \quad B_t \sim \text{Poisson}(\lambda)\]where

\[\lambda = \mu e^{ -\mu \Delta k(\pi,\tau,\mu)}\]is the growth rate of the honest chain—the block production rate μ multiplied by the probability that a produced block is not orphaned.

By analyzing this process, its statistical properties can be fully characterized by a single parameter: the system load:

\[\rho=\frac{\alpha}{\lambda k}\in[0,1)\]The load, $\rho$, is an indicator of system congestion. It measures the ratio of the incoming transaction data rate ($\alpha$) to the chain’s effective data-processing rate ($\lambda k$).

User Performance and Waiting Time

From a user’s perspective, the system’s load directly impacts the most critical performance metric: the expected waiting time for a transaction to be confirmed. In the vast majority of queuing models, as the load $\rho$ approaches 1, the average queue length (here, the mempool size) and the expected waiting time tend to grow exponentially. While our bulk-service model is more complex than a simple M/M/1 queue, the core principle is identical: a lower load means a less congested system and, therefore, shorter wait times.

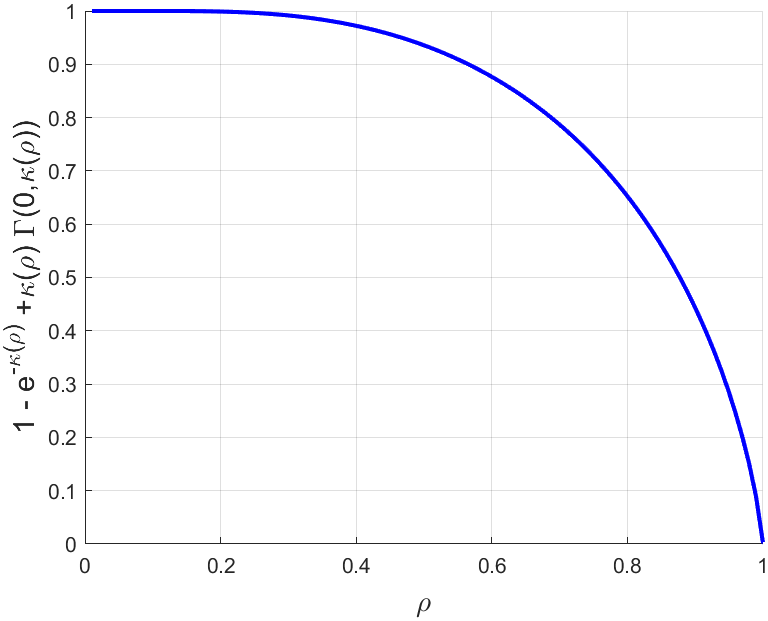

To further quantify this user experience, we can derive two specific metrics from the model:

- Partial‑utilization probability: This is the probability that all pending transactions in the mempool can be recorded in the next block. It effectively answers the user’s question: “Is the network currently congested?” A high probability indicates low congestion and implies a short expected waiting time for transaction confirmation.

- Block‑inclusion probability: This is the probability that a transaction arriving at a random time is included in the very next block. It directly answers: “What are the chances my transaction gets confirmed quickly?” It provides an immediate sense of the service delay a user will face.

Ultimately, all these user-centric metrics improve as the load $\rho$ decreases. For a given blockspace demand, an optimally designed system from a user’s point of view is arguably one that minimizes this load.

4. Optimality Conditions

We can now analyze the system’s performance from two different perspectives: what is best for miners, and what is best for users. The core of the analysis is to determine when these two objectives align or conflict.

- Miner Optimality: A parameter configuration state that maximizes the aggregate revenue of all miners.

- User Optimality: A parameter configuration that minimizes the system load $\rho$.

Miner-Optimal Capacity

From a miner’s perspective, the goal is to maximize their revenue per unit of time. Aggregate miner revenue is given by:

\[ \mu e^{ - \mu \Delta k } ( \pi+\tau k )\]This expression represents the rate at which non-orphaned blocks are produced ($\mu e^{-\mu\Delta k}$) multiplied by the reward for each successful block ($\pi+\tau k$). Maximizing this expression with respect to the block capacity $k$ yields the miner-optimal capacity:

\[k^{\mathrm{opt}}(\pi,\tau,\mu)=\frac{\mu^{-1}}{\Delta}-\frac{\pi}{\tau}\]As the number of miners $M$ tends to infinity, the Nash Equilibrium capacity chosen by individual miners, $k^{\mathrm{NE}}$, converges to this revenue-maximizing capacity, $k^{\mathrm{opt}}$.

User-Optimal Capacity

From a user’s perspective, the best system is the one that minimizes the load $\rho$ and thus their waiting time. The lowest possible load the system can achieve is the efficient load:

\[\rho^{*}= \min_{\mu,k>0} \frac{\alpha}{\mu k e^{-\mu\Delta k} }\]This minimum is obtained by finding the pair $(\mu^{ * },k^{ * })$ that maximizes the denominator, which represents the chain’s effective throughput. This occurs when the system is perfectly balanced, satisfying the condition:

\[\mu^{ * } = \frac{1}{ \Delta k^{ * } }, \qquad k^{ * } \in (0,\infty)\]Intuitively, this means the system is most efficient when the time to produce a block ($\mu^{-1}$) is exactly equal to the time it takes for that block to propagate ($\Delta k^{*}$). If blocks are produced faster than they can propagate, the network becomes unstable with forks. If they are produced much slower, the network is underutilized. This balance point maximizes the rate of useful data being added to the chain, thereby minimizing congestion for users.

The above formula extends to arbitrary block size the expression of the maximum sustainable block rate for a given latency. A similar formula appears in the distributed‑systems literature (e.g., Pass & Shi 2017) and in the economics literature (e.g., Hinzen et al. 2022).

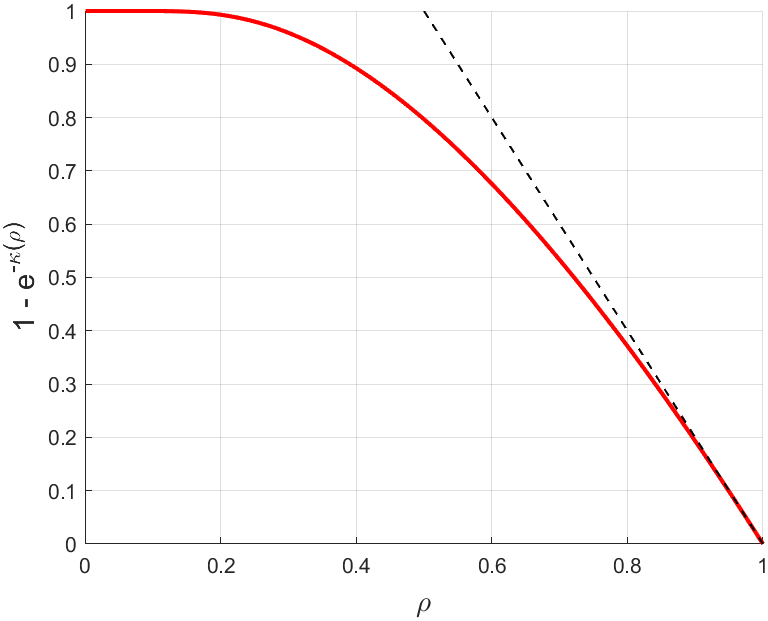

The Conflict: Why Miner Incentives Lead to Smaller Blocks

The crucial question now is whether the capacity chosen by miners, $k^{\mathrm{opt}}$, is the same as the capacity that is optimal for users, $k^{*}$. Comparing the two formulas reveals the conflict:

\[k^{*}=k^{\mathrm{opt}}(\pi,\tau,\mu)+\frac{\pi}{\tau}\]Since the coinbase $\pi$ and fee rate $\tau$ are non-negative, the competitive equilibrium chosen by miners yields a block capacity that is smaller than or equal to what is optimal for users:

\[k^{\mathrm{opt}}(\pi,\tau,\mu) \le k^{*}\]Equality—and thus a user-optimal outcome—is achieved only when the coinbase reward is zero ($\pi=0$).

Any positive coinbase ($\pi > 0$) incentivizes miners to produce blocks that are inefficiently small from a user’s perspective. The reason is that the coinbase is a large, fixed reward that a miner only receives if their block wins the race and is not orphaned. By shrinking their blocks, miners reduce propagation delay, increasing their chances of winning this fixed prize. They are willing to sacrifice some fee revenue (from a larger block) to improve the odds of securing the more valuable coinbase. This strategic choice leads to a higher system load and, consequently, longer waiting times for users.

5. Security Implications

In Nakamoto consensus safety is guaranteed only if honest miners burn at least as many resources per unit time as any attacker could.

Let

$A$: computational power of a hypothetical adversary (block rate),

$c$: unit cost of that power, so $A c$ is the attack cost per unit of time,

$\lambda$: rate at which the honest chain grows by one block,

$\pi+\tau k$: reward paid to the miner of such a block.

A minimal safety requirement is

\[\lambda(\pi+\tau k) \ge A c \qquad \text{(SC)}\]Suppose we suppress the coinbase $(\pi=0)$ to reach the efficient capacity ($\mu^{-1}=\Delta k$).

At this parameter configuration $\lambda k = 1/(e\Delta)$ because the fork probability equals $1- e^{-1}$.

Plugging into (SC) gives

Interpretation: To secure the chain using only fees, the fee income per unit of time must exceed the marginal cost of attacking the chain by a factor of e (≈ 2.718).

If inequality (FC) holds, security is achievable without a coinbase and the load attains its minimum.

Otherwise, a positive $\pi$ is required, miners reduce the equilibrium block size, and the system operates at a second‑best (higher) load.

6. Discussion and Caveats

Rewarding orphaned (“uncle”) blocks

How does the equilibrium change when miners are paid a coinbase reward ϕ even for forked blocks?

This shifts the equilibrium capacity (in the limit with many small miners) to

\[k(\pi,\tau,\mu,\phi)=\frac{\mu^{-1}}{\Delta}-\frac{\pi-\phi}{\tau}\]Setting $\pi=\phi$ neutralizes the fixed‑reward distortion, so the efficient capacity $k^{ * }$ is attained for any fee rate τ.

Hence uncle rewards enlarge the parameter region in which the chain can be both secure and efficient.

To assess the impact of uncle rewards, there are other considerations beyond this simplified setting: For example, if the attacker is rational, paying out $\phi$ may subsidize deliberate forking and weaken security guarantees.

Discrete latency

If propagation delay is piecewise (no delay below a packet size $\underline k$, full delay Δ above it), strategic complementarities generate multiple pure‑strategy equilibria. The qualitative comparative statics remain unaffected—larger Δ or higher $\pi/\tau$ induce miners to choose smaller blocks.

Block Size Limits

The model does not include a hard-coded maximum block size ($k^{max}$), which is a well-known feature of protocols like Bitcoin. In this framework, a miner can theoretically propose a block that absorbs the entire mempool.

This is a deliberate modeling choice, meant to isolate the balance between fee revenue and latency. In fact, based on the above model, the maximum size would never be binding, as due to the incentive structure of the coinbase reward, miners are already motivated to produce blocks that are inefficiently small.

A bit more formally, if a maxium block size (e.g., $k^{max}$) were present in the model, the strategic capacity chosen by miners would simply be $\min(k^{NE}, k^{max})$, but since the model shows $k^{NE}$ is already smaller than what is socially optimal, $k^{max}$ would not alter the analysis.

While latency is relevant for the choice of block size limits, for Bitcoin, the historical debate was driven by other concerns. In particular, it was driven by the need for spam prevention or the desire to create blockspace scarcity to foster a fee market through a priority auction.

Demand Elasticity and Fee–Reward Calibration

The model so far treats the transaction flow α as fixed. Taking the analysis one step further requires calibrating the elasticity of transaction demand to fees.

*Feedback welcome at michele.fabi@ensae.fr.