How scalable is Byzantine agreement? Does solving agreement require non-faulty parties to send a quadratic number of messages in the number of potential faults? In this post, we highlight the Dolev and Reischuk lower bound from 1982 that addresses this fundamental question.

Dolev and Reischuk 1982: any deterministic Broadcast protocol that is resilient to $f$ Byzantine failures must have an execution where the non-faulty parties send $> (f/2)^2$ messages.

In fact, we will observe that the result is stronger and holds even for omission failures:

Dolev and Reischuk 1982, (modern): any deterministic Broadcast protocol that is resilient to $f$ omission failures must have an execution where the non-faulty parties send $> (f/2)^2$ messages.

In a follow-up post we address randomization.

In 1980, PSL showed the first feasibility result for consensus in the presence of Byzantine adversaries. However, their solution had an exponential (in $n$, the number of parties) communication complexity. The obvious next question is to determine the lowest possible communication complexity. Dolev and Resichuk showed that the barrier to quadratic communication complexity cannot be broken by deterministic protocols.

At a high level, the Dolev and Resichuk lower bound says that if the non-faulty send few messages (specifically $< (f/2)^2$), then the adversary can cause some non-faulty party to receive no message! The party that receives no message has no way of reaching agreement with the rest.

Proof Intuition

- If a party receives no messages, it cannot decide like the other non-faulty parties.

- If a party receives few messages, the adversary can use omission failures to ensure that it receives no messages.

- If all parties receive many messages, then the total number of messages sent is large.

- Thus, any protocol that sends few messages must have some party that receives few messages, which can be exploited by the adversary to isolate it.

- But what if the party that has few messages sent to it, receives none due to receive omission, but in response sends messages that causes more messages to be sent to it?

- This is why the proof considers a world with $f/2$ candidate parties and corrupts all of them to not receive messages.

- If each of these parties receives $> f/2$ messages from non-faulty parties, then we have a protocol with $> (f/2)^2$ messages being sent by non-faulty parties.

- So if there exists a protocol sending fewer messages, there must exist one omission faulty party, say $p$, that receives $\leq f/2$ messages, that are all omitted by $p$.

- In the second world we uncorrupt $p$, and corrupt the at most $f/2$ parties sending messages to $p$ to omit messages to $p$.

- Hence, $p$ receives no message and the adversary corrupted at most $f$ parties.

Proof

Consider a broadcast problem, where the designated sender has a binary input. First, we need to guarantee that the isolated party $p$ will indeed not decide like all the other non-faulty parties. Consider a party that receives no messages: it will either not decide 0 or not decide 1. Without loss of generality, assume that a majority of parties (other than the designated sender) that receive no message will not decide 0 (so either decide 1 or never decide). Let $Q$ be this set of parties and note that $|Q| \geq (n-1)/2$.

We will prove the theorem by describing two worlds and using indistinguishability for all honest parties.

World 1:

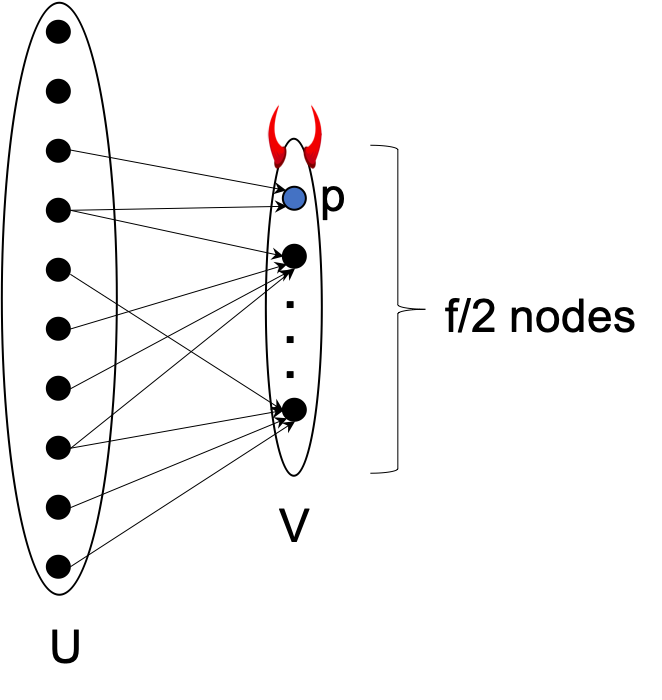

In World 1, the adversary corrupts a set $V \subset Q$ of $f/2$ parties that do not include the designated sender. Let $U$ denote the remaining parties (not in $V$). All parties in $V$ run the designated protocol but suffer from omission failures as follows:

- Each $v \in V$ omits the first $f/2$ messages sent to $v$ from parties in $U$,

- Each $v \in V$ omits all messages it sends to and receives from parties in $V$.

Note that messages sent from parties in $V$ to parties in $U$ are not omitted.

Set the non-faulty designated sender with input 0. So from the validity property all non-faulty parties must output 0. Since the non-faulty parties send at most $\leq (f/2)^2$ messages, then there must exist some party $p \in V$ that receives $\leq f/2$ messages.

World 2:

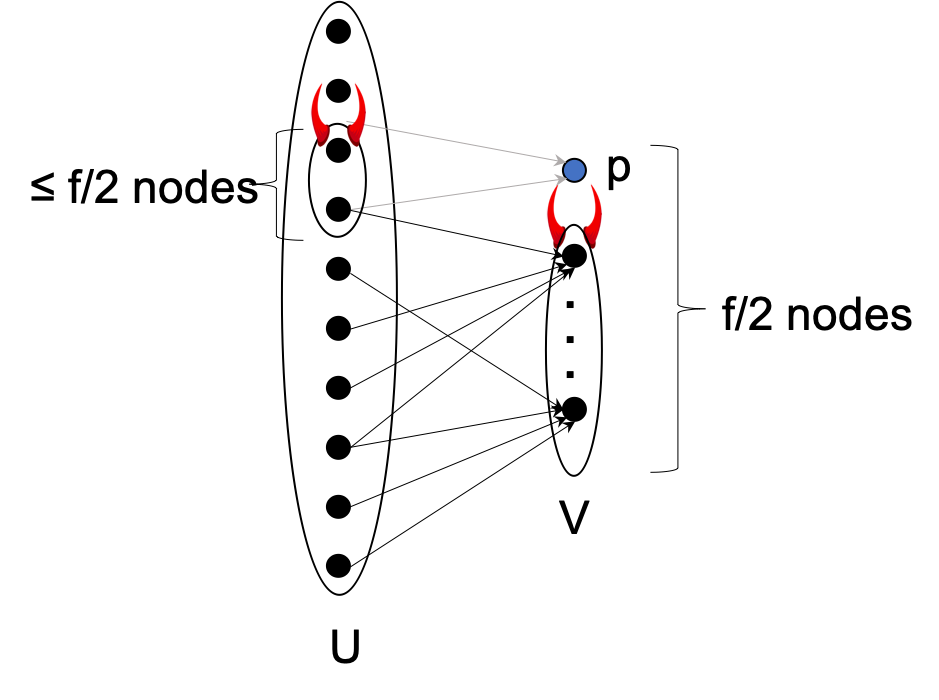

In World 2, the adversary does everything as in World 1, except (i) it does not corrupt party $p$, and (ii) it corrupts all parties in $U$ that send messages to $p$ (this may also include the designated sender). Messages sent by these omission corrupt parties to $p$ are omitted. Since $p$ received $\leq f/2$ messages in World 1, at most $f$ parties are corrupted in World 2 ($\leq f/2$ senders plus $|V| = f/2$).

What do honest parties in $U$ output in World 2? We argue that they will output 0. Observe that for the non-faulty parties, the two worlds are indistinguishable. Since the protocol is deterministic, they receive exactly the same messages in both worlds. However, since party $p$ does not receive any messages and $p \in Q$, then it will not output 0, so will either violate the agreement property (if it outputs 1) or violate the termination property (if it does not output anything).

Extending the lower bound

The lower bound uses the fact that the protocol is deterministic. There have been several attempts at circumventing the lower bound using randomness and even against an adaptive adversary. Here are a few notable ones:

- King-Saia: Through a sequence of fascinating new ideas, King and Saia presented a beautiful information-theoretic protocol that broke the quadratic communication complexity. Their protocol uses randomness, assumes that honest parties can erase data, and does not allow the adversary to claw back messages.

- Algorand uses cryptographic randomness (VRFs) to form small committees. Algorand assumes the adaptive adversary is weak: it cannot cause the corrupt parties to remove the in-flight messages that were sent before the party was corrupted.

- Randomized version of Dolev-Reischuk. Any (possibly randomized) Byzantine Agreement protocol must in expectation incur at least $\Omega(f^2)$ communication in the presence of a strongly adaptive adversary capable of performing “after-the-fact removal”, where $f$ denotes the number of corrupt parties (see paper).

- The above result implies that even against a static adversary, any protocol that runs in $o(n^2)$ complexity must have a non-zero probability of error.

- The work of Spiegelman, DISC 2021 proves a generalization in the early stopping setting: if the actual number of failures in an execution is $k\leq f$ then $\Omega(f+kf)$ messages are required.

- See this follow-up post on new Dolev-Reischuk style lower bounds for Crusader Agreement against a Byzantine adversary.

Broadcast vs Agreement

The lower bound is presented for Broadcast (not Agreement). In terms of feasibility, the two problems are equivalent. In particular, if Agreement can be solved with communication complexity $\leq Y$ then broadcast can be solved in communication complexity $\leq Y+n$; the leader can send the value to all parties, and then they can run the Agreement protocol. Thus, if $(f/2)^2$ messages are required for Broadcast then at least $(f/2)^2 - n$ messages are required for Agreement.

This post was updated in November 2021 to reflect that the lower bound holds for omission failures.

Please leave comments on Twitter