This post is about the work of Stuart Haber and W. Scott Stornetta from 1991 on How to Time-Stamp a Digital Document and their followup paper Improving the Efficiency and Reliability of Digital Time-Stamping. In many ways, this work introduced the idea of a chain of hashes to create a total order of commitments to a dynamically growing set of documents. It’s no wonder these two papers are cited by the Bitcoin whitepaper.

Who watches the watchmen? Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? – Juvenal

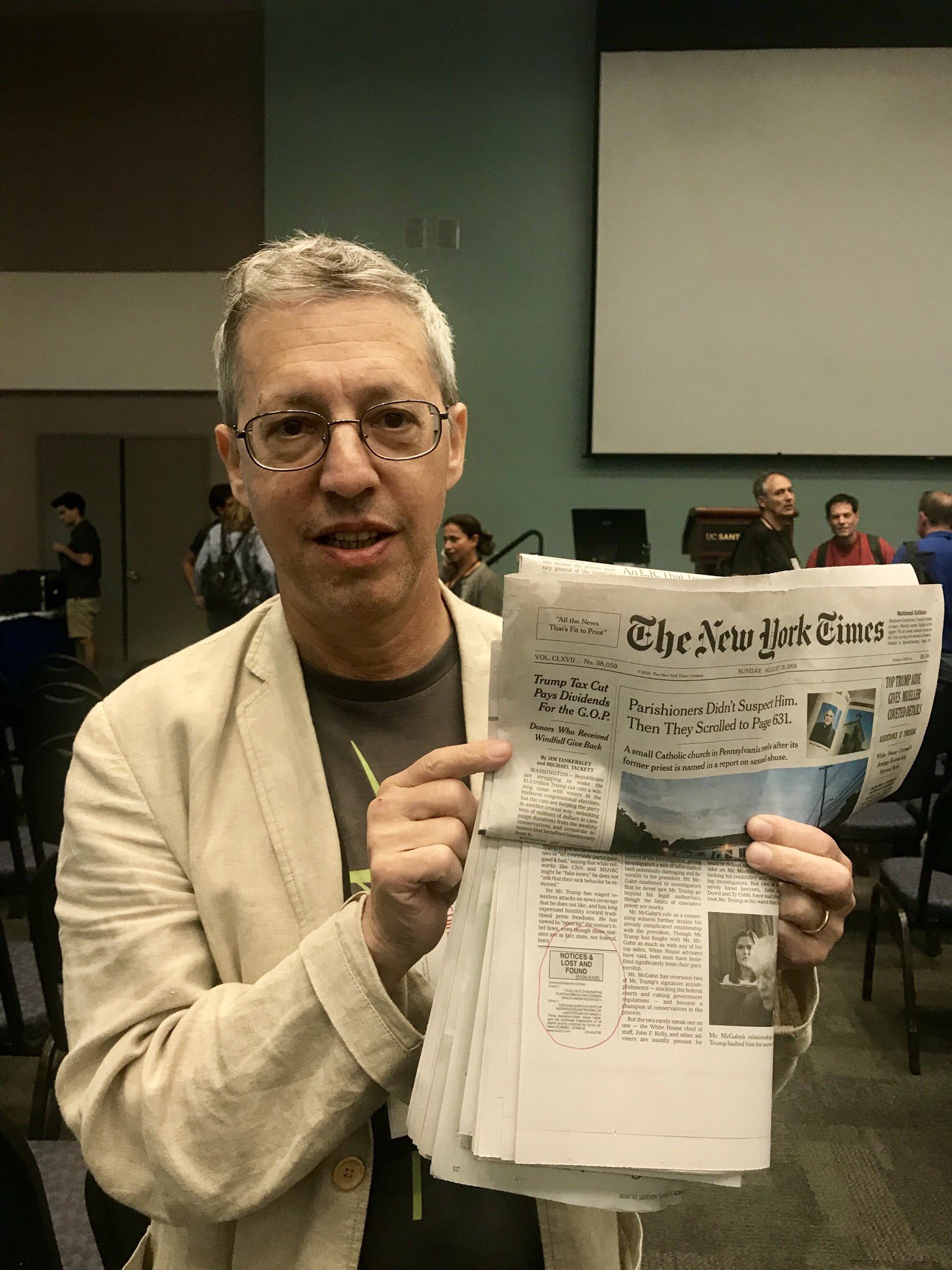

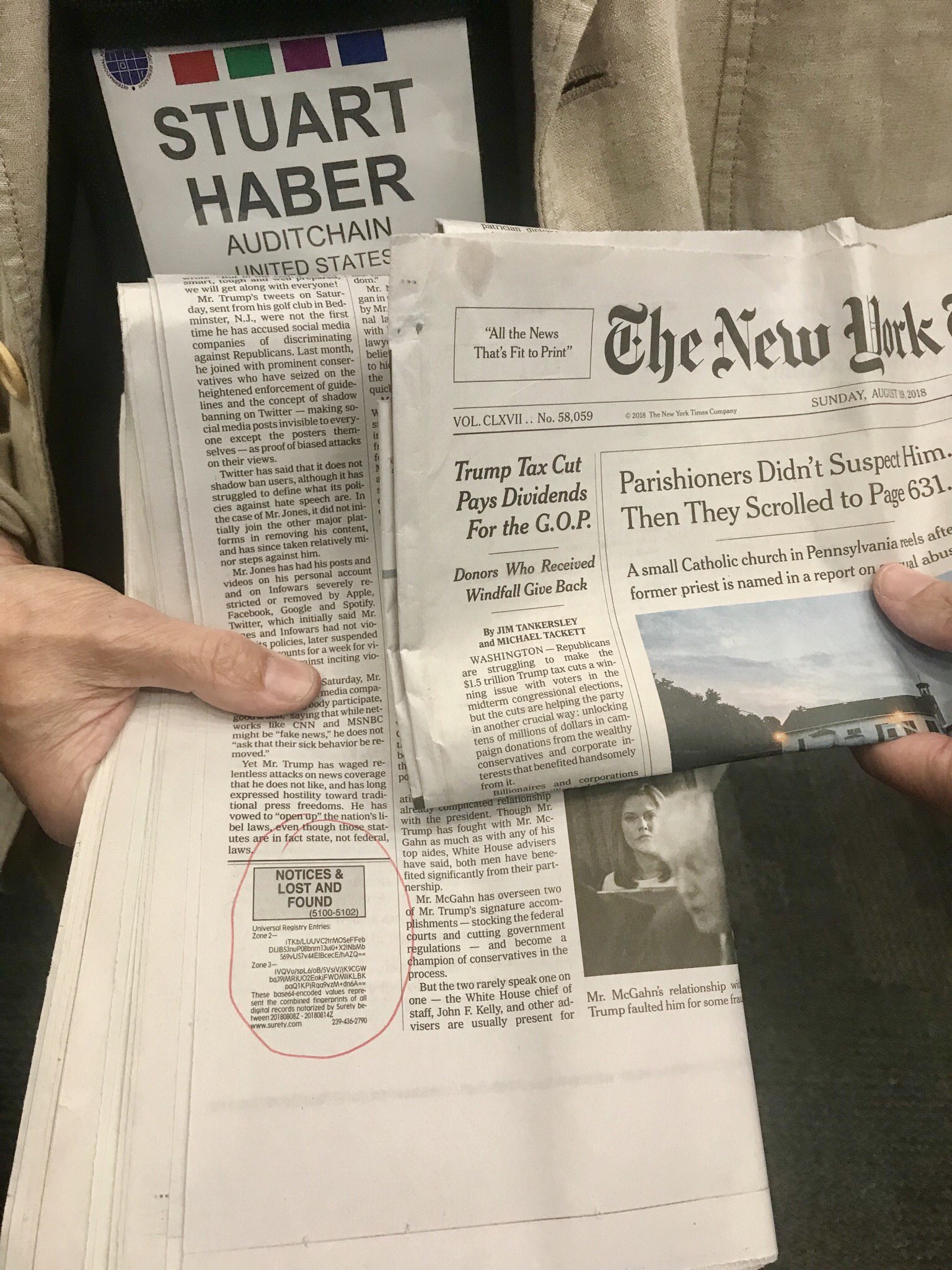

From 1995, the ideas of this paper have been in use by a company called Surety. This makes it the longest-running chain of hashes! Here are two photos from 2018 of Stuart Haber with the current hash circled in red on the New York Times:

How to Time-Stamp a Digital Document?

In 1991, Haber and Stornetta asked this very basic question. Today, after 30 years of exponential growth in digital documents, this question is even more relevant! Let’s describe their basic scheme:

The system is composed of users, a Time-Stamp Service (TSS), and a repository. At some regular interval, the TSS publishes an “interval hash” to a “widely available repository”.

-

Users send certification requests to the TSS.

-

The TSS creates a Merkle tree of all the requests.

-

The “hash chaining” happens: The new interval hash is computed by taking the root hash of the Merkle tree and hashing it with the previous interval hash.

-

The TSS publishes the new interval hash to the public repository.

-

The TSS also sends each requester a Merkle proof that their document is committed in the Merkle tree.

-

Users can validate a document’s time-stamp by querying the repository for the relevant interval hash and use the Merkle proof to compare the relevant leaf to the hash of the document.

In their own words, if we assume the repository is durable and trusted (think about the New York Times weekend circulation) then:

-

“The TSS cannot forward-date a document, because the certificate must contain bits from requests that immediately preceded the desired time, yet the TSS has not received them.” – note that this assumes there is enough uncertainty in the future requests that is beyond the control of the TSS.

-

“The TSS cannot feasibly back-date a document by preparing a fake time-stamp for an earlier time, because bits from the document in question must be embedded in certificates immediately following that earlier time, yet these certificates have already been issued.” – Note that this assumes the hash function is collision-resistant.

-

“The only possible spoof is to prepare a fake chain of time-stamps, long enough to exhaust the most suspicious challenger that one anticipates.” – quite remarkable that even the notion of the longest chain has origins in this paper!

Note that there are some underlying assumptions here. We are trusting the TSS (Surety) to not censor users and we are trusting the repository (New York Times) to be durable and show a consistent version to all users.

This is a very simple and intuitive scheme. It does make quite strong trust assumptions. Can we remove them?

Connection to Bitcoin and Cryptocurrencies

The Bitcoin whitepaper made a breakthrough connection between this time-stamping scheme and proof-of-work: instead of assuming a centralized trusted TSS and a centralized trusted repository, it uses the chain of hashes to incentivize miners to implement the TSS and the repository in a decentralized manner! A miner that wins the race to produce a proof-of-work is incentivized to implement the TSS functionality and correctly publish a new interval hash. Censorship resistance is obtained by randomizing the winning miner and by adding fees that reward adding user requests. Miners are collectively incentivized to implement a replicated repository. Consistency is obtained by incentivizing miners to use the notion of the longest (PoW heaviest) chain of hashes.

Seen from the lens of distributed computing, the Bitcoin blockchain implements the TSS state machine and the repository is replicated via a byzantine fault-tolerant protocol called Nakamoto Consensus. Seen from the lens of game theory, the contents of the documents recorded are restricted to be transactions over an internal digital asset with a controlled supply. Using this scarce resource, Bitcoin builds a novel incentive scheme that typically incentivizes miners to implement the TSS and the public repository.

Is it only about Cryptocurrencies?

The ability to order (time-stamp) all transactions in a trusted and immutable manner is a key ingredient of many decentralized state machines. This is a core enabler of many cryptocurrencies.

There could be many other cases where a trusted method to time-stamp digital documents is beneficial and a central trusted party is acceptable. Here are some examples:

-

The git protocol implements a hash chain on all commits. In a way, GitHub can be viewed as a centralized implementation of a TSS and public repository for documents (in particular, for code).

-

Certificate transparency uses a chain of hashes (in fact, a Merkle tree) to maintain a public log of certificates and their revocations.

-

The InterPlanetary File System (IPFS) protocol uses elements of the TSS and repository idea to build a verifiable file system with a global namespace using a Distributed Hash Table (DHT).

-

Digital news outlets, blogs, or any web server could be able to provide a signed certificate of the time-stamp of their documents. For example, a blogger could prove that their posts are not backdated.

-

Educational institutions, Medical institutions, Government authorities could be able to provide a signed certificate of the time-stamp of their documents. This could allow digital verification of certificates of education, health, licenses, title, and more.

-

Financial institutions and multi-party business transactions could all rely on a trusted party to sign certificates about financial facts. Having a single source of truth that all parties can verify could reduce friction and risk in many transactions.

I can imagine that sometime in the future many digital documents will use some form of time-stamp based on the work of Haber and Stornetta.

Acknowledgment. Thanks to Kartik, Avishay, Ittay, and Alin for helpful feedback on this post.

Please leave comments on Twitter.